India’s Bigger Soft Infrastructure Challenge

In the race to build infrastructure on the ground, India is restrained by lack of talent and capacity to execute the plans laid out by the Central Government under the ambitious Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission (JNNURM).

In the race to build infrastructure on the ground, India is restrained by lack of talent and capacity to execute the plans laid out by the Central Government under the ambitious Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission (JNNURM).

JNNURM was launched in December 2005 with a total outlay of Rs 66,084 crore. Despite the promise of bettering lives for some 377 million urban Indians, it has had limited success. Largely because scores of projects have just not got off the ground or are hugely behind schedule.

In states like Uttar Pradesh, for example, just one project has been completed as against an allocated 33 projects. States like Assam, Haryana and Punjab have made absolutely no progress. Gujarat, on the other hand, hand completed 38 projects as against the allocated 72 projects. Karnataka has managed to complete 22 out of the 47 projects.

A recent Comptroller & Auditor General (CAG) report says the programme was expected to get over Rs 66,000 crore during the mission period 2005-06 to 2011-12. As against this, Rs 45,066 crore was the actual budgetary allocation till 2012. And nearly 90% of the budgetary allocation (Rs 40,584 crore) was released for various programmes of the mission.

One key reason for the shortfall in implementation and fund utilisation is the inability of local administration to build the right project implementation capabilities. This includes writing detailed project reports (DPRs) based on which funds could be handed out. This gap – referred to as capacity building – will be one of the biggest challenges in India’s infrastructure ambitions.

A quick background on JNNURM: the programme is focused on improvement in four key areas - efficiency of urban infrastructure, efficiency of service delivery, community participation in the decision-making process and accountability & transparency. The Mission is further split into two sub-missions: Urban Infrastructure and Governance (UIG) and Basic Services to the Urban Poor (BSUP). Two other components were added later to accommodate more cities and towns - Urban Infrastructure Development for Small and Medium Towns Scheme (UIDSSMT) and Integrated Housing and Slum Development Programme (IHSDP).

So, let’s understand what capacity building means. The Planning Commission defines it as “the effort to strengthen and improve abilities of personnel and organisations to be able to perform their tasks in a more effective, efficient and sustainable manner.”

Translated, it means two things: people involved in the actual project work have to be able to execute projects better and also ensure that the projects become self-sustaining. They also have to be trained to write project reports according to standards set by the funding body (in this case the Central Government).

Second, the urban local bodies (ULBs) or municipal corporations have to master the art of raising funds to fulfill their share of funding the projects and also become self-sustaining at a later stage….

On both counts, the system has lagged. A mid-term appraisal of the 11thPlan (2010) on urban development by the Planning Commission points out that most central assistance has been directed towards hard infrastructure while improvements in soft infrastructure have been stated as conditions for the cities and states to fulfill mostly on their own.

“Much more emphasis should now be on proactive assistance to cities and states to build their soft infrastructure,” it says. Two efforts by the central government can be highlighted when it comes to Improving capacity of ULB.

Firstly, World Bank offered the Indian Government a $60 million credit line in 2011 for better infrastructure management by ULBs.

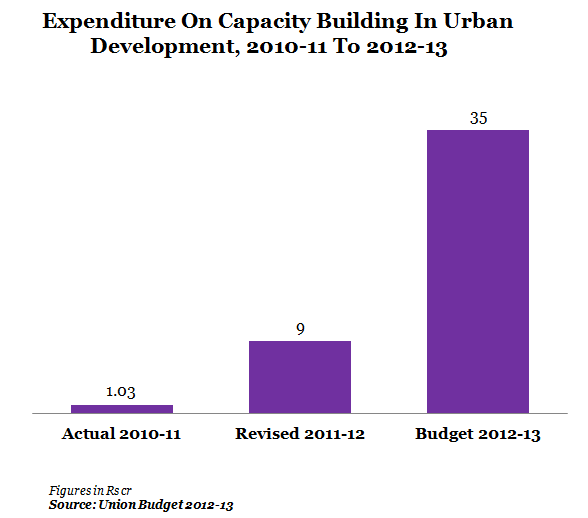

The following table shows the budget allocations based on the demand for grants in the last three budgets for World Bank loan:

Figure 1

The success of the capacity building initiative is further linked to reforms under the JNNURM programme. And there are five sets of reforms that aim to improve the financial capacity and governance of the ULBs.

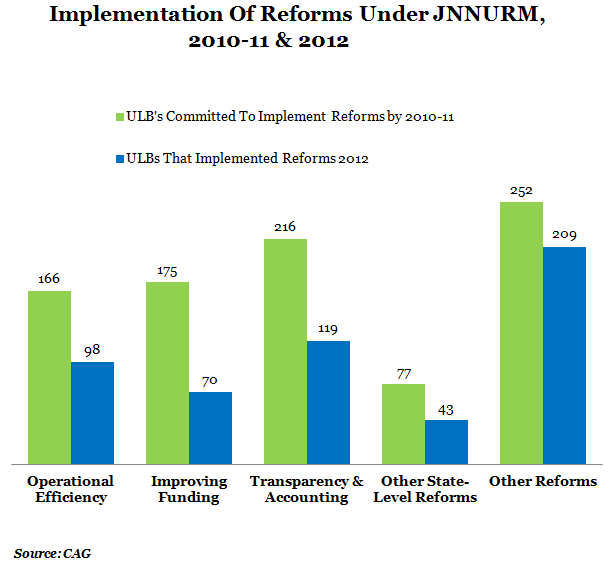

Each ULB has to complete at least 50% of the reforms to gain funding from the Central Government. The following table shows the implementation of reforms under JNNURM:

Figure 2

The table suggests that the number of reforms committed by the ULBs were high but the rate of implementation has been very low. It also tells us that most ULBs were unable to implement reforms relating to financial matters. For example, under ‘augmenting sources of funding’, only 52% ULBs could implement the proposed reforms on property taxes.

The best measurement of urban renewal-and-build is perhaps the outcome. Training people and creating the resources to better administer infrastructure projects, particularly in the Government domain, can be a painful process. But there is no choice. And time is, indeed, running out.