2 Million Reasons India Should Restrict Antibiotics

Minimum effort. Minimum expense. Maximum result.

In colloquial English, that’s the mantra that guides India, a mantra that has helped it become a global centre for low-cost innovation—and kept the country addicted to slapdash, jerryrigged solutions to complex problems.

One of these careless solutions—seeking quick, cheap solutions to common colds and fevers—now threatens to place 2 million Indians at risk of dying every year by 2050, a British economist estimated earlier this month.

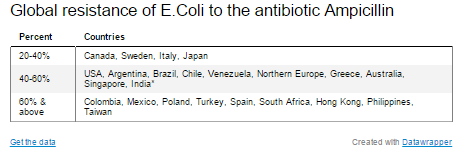

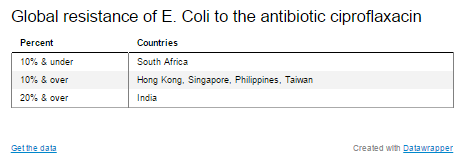

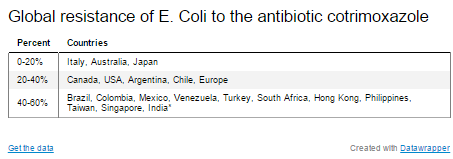

The cause of these deaths would be the impending failure of antibiotics, medicines hailed as wonder drugs in the 1940s when they first demonstrated powerful abilities to stop harmful bacteria. That failure is directly connected with India’s pill-popping habit, which has seen antibiotic use soar by 62% over the last decade, against 36% across the world, according to the latest data from Princeton University in the US.

Antibiotics, available strictly on prescription in the West and many emerging nations, are sold over the counter in India. Giving in to patient demands to get treated quickly and cheaply, many general practitioners prescribe one of several popular antibiotics. Many patients simply self-prescribe antibiotics.

In hospitals across India, there is growing concern about short-cuts to treat fevers, sore throats and colds without laboratory investigations required to determine if, for instance, a fever is a caused by a virus or a bacteria.

The hot-fluids-and-rest prescription works for coughs and colds, infections caused by a virus, which can only replicate inside living cells. Antibiotics have no effect on viral infections but can be used only for a bacterial infection that could worsen into, say, pneumonia.

Globally, overprescribing antibiotics—or, prescribing it when a simpler drug would do—is the biggest reasons for the evolution of antibiotic resistant pathogens, disease-causing organisms.

"Some experts say we are moving back to the pre-antibiotic era," said Margaret Chan, director general of the World Health Organisation earlier this year. "No. This will be a post-antibiotic era. In terms of new replacement antibiotics, the pipeline is virtually dry...the cupboard is nearly bare."

India’s cupboard is in danger of getting bare quicker than anywhere else in the world.

The bacterium and the bare cupboard of India

Resistance begins when people take antibiotics for "acute, self-limiting" infections, such as diarrhoea, and fever-driven illnesses where these drugs simply do not work, such as dengue fever, malaria or chikungunya, Dr Sumanth Gandra, co-investigator on the Princeton Study told IndiaSpend in an email interview.

When bacteria gain resistance to an antibiotic, they must be treated with ever-stronger medicines, until, one day, nothing is left in the cupboard.

Consider Neisseria gonorrhoeae, a bacterium that causes severe infection of the reproductive tract in women. Left untreated, it can cause infertility and increase the risk of acquiring HIV.

“Neisseria gonorrhoeae can no longer be cured by sulfonamides, penicillin, tetracyclines or fluoroquinolones, not just in India but in any part of the world," said Gandra, an infectious-diseases expert and fellow at the Center for Disease Dynamics, Economics & Policy (CDDEP) a public-health research organisation based in Washington D.C. and New Delhi. "Most cases globally are responding to injectable third-generation cephalosporins (a late-generation antibiotic derived from a fungus). A few cases are showing resistance to even this last-line agent.”

Once resistance begins, it is a matter of time before it grows and spreads across this globalised, interconnected world.

In 2010, all hell broke loose in the Indian medical world when Timothy Walsh, a professor at Cardiff University’s School of Medicine suggested that some patients suffering from antibiotic-resistant bacteria in UK hospitals acquired the superbug in Delhi.

Not long before they fell ill, these patients had spent time in Delhi,some were even in Delhi hospitals. Indian authorities were incensed at the suggestion and the name he gave to the gene that could resist the latest group of antibiotics. The gene is called NDM-1, or New Delhi Metallo-beta-lactmase-1.

The following year, Walsh went on to see if he could locate traces of the superbug in the wider environment in Delhi. He did, as a study reported.

"I found bacteria carrying the gene in two of 50 drinking-water samples and 51 of 171 seepage samples,” Walsh told IndiaSpend.

India’s health ministry spokesperson at the time, R K Srivastava, said that bacteria exist naturally everywhere, and there was no evidence that anyone had become ill as a result.

Mobile bacteria, mobile genes

Bacteria do exist everywhere: from the air we breathe to the human gut. Not all bacteria are pathogenic, or harmful. Many are useful, especially those in the gut. Even good bacteria can carry the NDM-1 gene or any other gene that confers antibiotic resistance.

Bacteria can easily share plasmids, small DNA molecules carrying their genes, and thus easily share their resistant traits with other bacteria. This means any good bacterium carrying an antibiotic resistance gene could pass on this genetic information to other good and bad bacteria.

With gut bacteria, the chances of that happening may increase when you take antibiotics, because bacteria, like every species, evolve to survive. “The NDM-1 gene has found its way to over 40 species of different bacteria, which is unprecedented in antibiotic resistance,” said Walsh.

Given the appalling state of sanitation in India, it isn’t surprising that the majority of adult Indians carry highly resistant bacteria in their gut. Walsh said his team, in 2013, found that 90% of adults in south Pakistan carried a gene that made common bacteria that live in the intestines of healthy people resistant to potent antibiotics.

"We believe the same statistics apply to northern and urban India," Walsh said. “In contrast, only 10% of adults in the Queens area of New York carry bacteria bearing the same gene.”

All these adult Indians could contribute to the evolution of superbugs, if they were to abuse antibiotics. It appears Indians are doing just that. The country is not yet a hotbed of super- resistant pathogens, but if NDM-1 transfers to highly pathogenic bacteria, it could happen very soon.

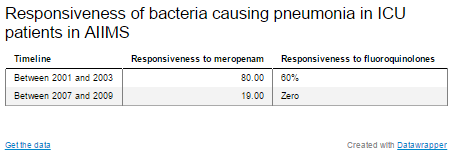

At India’s largest public hospital, the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS) in New Delhi, doctors are already experiencing the era of antibiotic resistance. They will tell you how bacteria causing pneumonia in intensive care unit patients are much less responsive to antibiotics today than they were a decade ago.

Between 2001 and 2003, such pathogens used to be fairly responsive to antibiotics, being vanquished at a rate of 80% when doctors used a drug called Meropenem. Between 2007 and 2009, that rate fell to 19%. In the case of Ciprofloxacin, the effectiveness fell from 60% to 0, the Indian Express reported in 2012, quoting an AIIMS study of data gathered over 10 years.

Resistance in the ICU, resistance through chicken

Shaky infection-control practices in hospitals—a bane of health facilities, especially in low- and middle-income countries—are intensifying the global antibiotic-resistance challenge. Doctors are finding it that much harder to treat patients with hospital-acquired infections.

To dodge or confuse the process of resistance, medicine has learned to create combinations of antibiotics. For instance, at AIIMS, two antibiotics (Piperacillin-Tazobactam or Cefoperaone-Sulbactam) are used against a bacterium that commonly causes pneumonia in ICU patients. Physicians could be sure of a 100% cure only with a combination of antibiotics (called Colistin-Tigecycline), medicines that the European Medecines Agency calls "life-saving treatments for human patients suffering from different kinds of infections caused by multidrug-resistant bacteria".

But in time, pathogens will develop resistance even to these life-saving combinations.

The tides of resistance flood humanity from unexpected angles, such as the seemingly innocuous, small concentrations of antibiotics to keep diseases at bay in livestock and poultry.

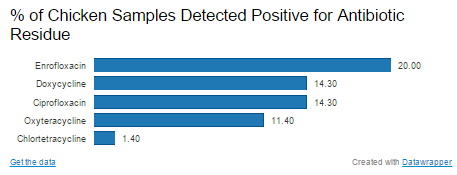

Earlier this year, 40% of poultry samples tested for six antibiotics by the Centre for Science and Environment (CSE), a Delhi-based advocacy, tested positive for antibiotic residue; 22.9% of the samples contained residues of one antibiotic and 17% had residues of more than one.

“Antibiotic-resistant bacteria could develop in the chicken itself and get transferred to humans eating meat," said Chandra Bhushan, CSE’s deputy director general. "Or, it (resistance) could develop in humans ingesting or handling tainted meat, as the body is continually subjected to the antibiotic. Concerns also surround farm waste entering into crops and water bodies—just the same as untreated sewage.”

Confronted with any mention of superbugs, Indian authorities have been quick to bury their heads in the sand. India’s previous health minister even shelved a national antibiotic policy, which would have banned over-the-counter sales of antibiotics and prohibited the use of other second-line antibiotics, except in major hospitals. The minister’s argument was that a ban might affect healthcare in rural areas, where many people don’t have access to hospitals, only to a local drugstore.

The dark ages of medicine?

Co-investigator of the Princeton Study, Gandra, suggests studying the patterns of antibiotic dispensing in pharmacies and framing better—and more realistic—policies. A study by the CDDEP in Karnataka’s Tumkur district, he said, found that most people visiting rural pharmacies have seen a medical practitioner and have a prescription, unlike their urban counterparts, who are more likely to self-prescribe." If more studies find similar results, then eliminating over-the-counter availability in urban areas would be more appropriate," said Gandra.

The problem is, time is on bacterium’s side.

Bacteria are engines of evolution, unexpectedly presenting nasty surprises.

Earlier this year, following the death of a man in Aligarh of a kidney infection that should have responded to strong antibiotics, scientist Dr Asad Ullah Khan of Aligarh Muslim University discovered bacteria bearing the NDM4 gene, a more virulent strain of NDM1, in the hospital’s drains.

In contrast, no new miracle mother-of-all antibiotics is on the threshold of discovery. The economics of antibiotic research simply don’t add up.

“Antibiotics yield a poor return on investment vis-à-vis drugs for chronic conditions—like lipid lowering agents, anti-hypertensives etc.," said Gandra.

“ALL antibiotics will eventually be rendered useless,” said Dr Camilla Rodrigues, consultant microbiologist and Chairperson, Infection Control Committee, P. D. Hinduja National Hospital and Medical Research Centre, Mumbai, to IndiaSpend in an email interview.

Ignoring this wake-up call will bring India closer to O’Neill’s prediction that 2 million Indians, of 10 million globally, will die of microbial diseases currently treatable.

In effect, that means the annual global death toll of antimicrobial resistance would be the same as cancer, cholera, diabetes, measles, tetanus, diarrhoeal conditions and road traffic accidents in the world, put together.

Antibiotics should be regarded for what they are—a global resource with an expiry date.

“What clinicians should do to delay the onset of resistance is prescribe antibiotics only for bacterial infections and revisit the duration of the antibiotic course,” said Dr Rodrigues.

If India resists the impulse to the antibiotic short cut, it could be on a fast path to what UK Prime Minister David Cameron called being "cast back into the dark ages of medicine".

Image Credit: Luchschen|Dreamstime.com

___________________________________________________________________________

“Liked this story? Indiaspend.org is a non-profit, and we depend on readers like you to drive our public-interest journalism efforts. Donate Rs 500; Rs 1,000, Rs 2,000.”