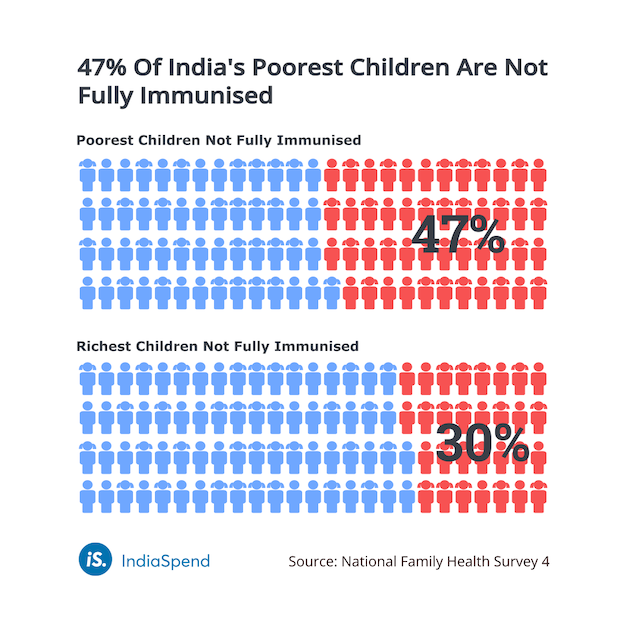

47% Of India’s Poorest Children, 30% Of Richest Not Fully Immunised

Mumbai: Nearly 47% of India’s poorest children are not fully immunised, 17 percentage points more than the richest children, according to national health data, leaving them prone to preventable disease and their households susceptible to catastrophic health expenditure. Besides household wealth, factors such as parents’ literacy, birth order and place of birth affect vaccine coverage, data show.

Children aged 12-23 months who had received one dose each of Bacille Calmette Guerin (BCG) vaccine for tuberculosis and measles vaccine, and three doses each of Diphtheria-Pertussis-Tetanus (DPT) vaccine and polio vaccine, were counted as fully immunised. Nationwide, 38% of children were not fully immunised, as per data from the National Family Health Survey 4 (2015-16) (NFHS-4).

Vaccines saved 10 million lives between 2010 and 2015 worldwide, according to World Health Organization (WHO). Additionally, millions of people were saved from the suffering and disability associated with diseases such as pneumonia, diarrhoea, whooping cough, measles, and polio.

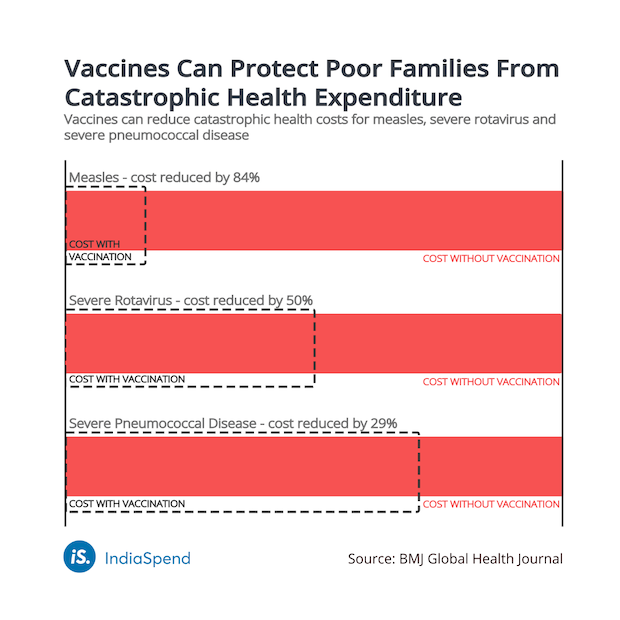

Further, vaccines can reduce catastrophic health costs--crossing a certain threshold of household expenditure--by 84% for measles, 29% for severe pneumococcal disease, and 50% for severe rotavirus, thereby protecting poor families from medical impoverishment, according to this 2018 study by Carlos Riumallo-Herl of the Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health.

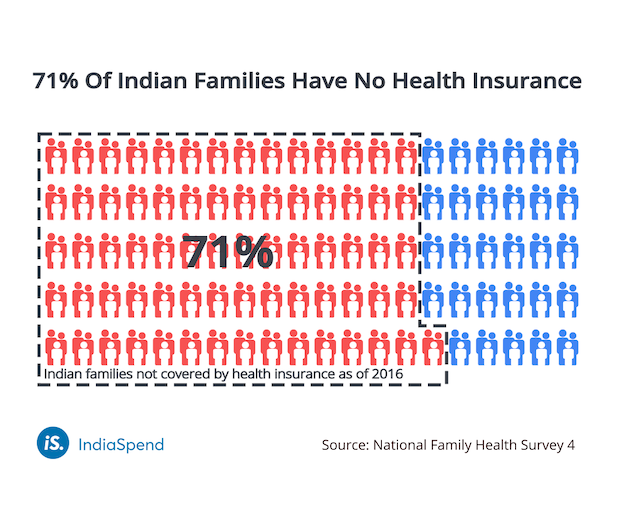

This is critical in India where nearly 71% of families don’t have a single member covered by health insurance as of 2016, according to National Family Health Survey, 2015-16. This percentage is higher for the poorest families, with approximately 78% of families not being insured. Indians are the sixth biggest out-of-pocket health spenders in the low-middle income group of 50 nations, we reported in May 2017. These costs push around 32-39 million Indians below the poverty line every year, according to various studies.

The burden of catastrophic health costs is greater on poor families, the study said, adding that expanding vaccine coverage will better protect them against financial risk.

Immunisations yield a net return about 16 times greater than the costs of treating illness over a decade, according to a 2018 study by Sachiko Ozawa, at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, which assessed return on investment of increasing vaccine coverage in low and middle-income countries. (India is a lower-middle income country).

Why are only 53% of children from poor families fully immunised?

“Poverty is not the only determinant for low vaccine coverage,” Susmita Chatterjee, Health Economist from the Center for Disease, Dynamics, Economics and Policy, told IndiaSpend. “Other factors such as belonging to a minority group, and low female literacy are some other determinants that interact with poverty and cause low coverage.” Minorities belonging to poor families have lower coverage, she added.

The odds of complete vaccination were lower in female children and Muslim families, according to this 2016 study conducted by Niveditha Devasenapathy, Indian Institute of Public Health in an urban poor community in Delhi. The odds of complete vaccination were higher if the mother was literate, if the child was born within the city (not migrated), born in a health facility, or possessed a birth certificate.

Muslims had lower vaccine coverage (55.4%) as compared to others (62%), and vaccination coverage increased with mother’s schooling, NFHS-4 data show.

Nearly 70% children aged 12-23 months whose mothers had 12 or more years of schooling received all basic vaccinations, compared to 52% children whose mothers had no schooling. Poverty is also connected to literacy levels: about 3% of women and 7% of men in poor families completed 12 or more years of schooling compared to 51% of women and 58% of men from the richest families, according to NFHS-4.

First-born children are also more likely to receive all basic vaccinations than the sixth or later child (67% versus 43%), which again is connected to poverty, according to the report.

Higher number of children per family increases health, information and education deprivation thus worsening poverty, as IndiaSpend reported on July 9, 2019. Families with children suffer a 22% poverty rate while families without children record an 8% poverty rate.

How Mission Indradhanush expanded vaccine coverage

In 2014, the Centre launched Mission Indradhanush, which intends to achieve full coverage of the country’s population by 2020 through intensified efforts.

“Villages usually have Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs) and where there aren’t ASHAs there are sub-centers in rural areas,” Chatterjee told IndiaSpend. “But in urban areas, such basic support is not easily accessible.”

Between 2014 and 2018--after Mission Indradhanush was launched--overall immunisation coverage for Indian children aged 12-23 months rose 29 percentage points--from 62% to 91%, approximately 7 percentage points per year. Prior to this, between 2006 and 2014, immunisation coverage rose 18 percentage points--from 44% to 62%, approximately 2 percentage points per year.

The British Medical Journal selected the programme as one of the 12 best practices globally, as The Times of India reported in December 2018.

In October 2017, Prime Minister Narendra Modi launched the Intensified Mission Indradhanush--which advanced the target to achieve over 90% immunisation to December 2018. “Let no child suffer from any vaccine-preventable disease,'' he said.

While campaigns and community outreach programmes can lead to an uptick in immunisation coverage, improving female literacy may be more sustainable and effective, Devasenapathy said in her 2016 study. Raising women’s literacy will improve their decision-making powers and ability to overcome social and cultural barriers.

This story was first published here on Healthcheck.

(Pankti Antani, an undergraduate student of finance at CUNY Baruch College, New York, is an intern with IndiaSpend.)

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@indiaspend.org. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.