Changed Tastes May Hurt Craftspersons Long Past Lockdown

Noida: Sanganer, the suburban hub of the hand-block printed textile industry near Rajasthan’s capital Jaipur, is shorn of its usual vibrancy and colour. Exporters of the prized Sanganeri textile say altered consumption patterns and diminished purchasing power in their primary markets in the US and Western Europe will continue to hurt their livelihoods long after the lockdown is lifted and their workers return.

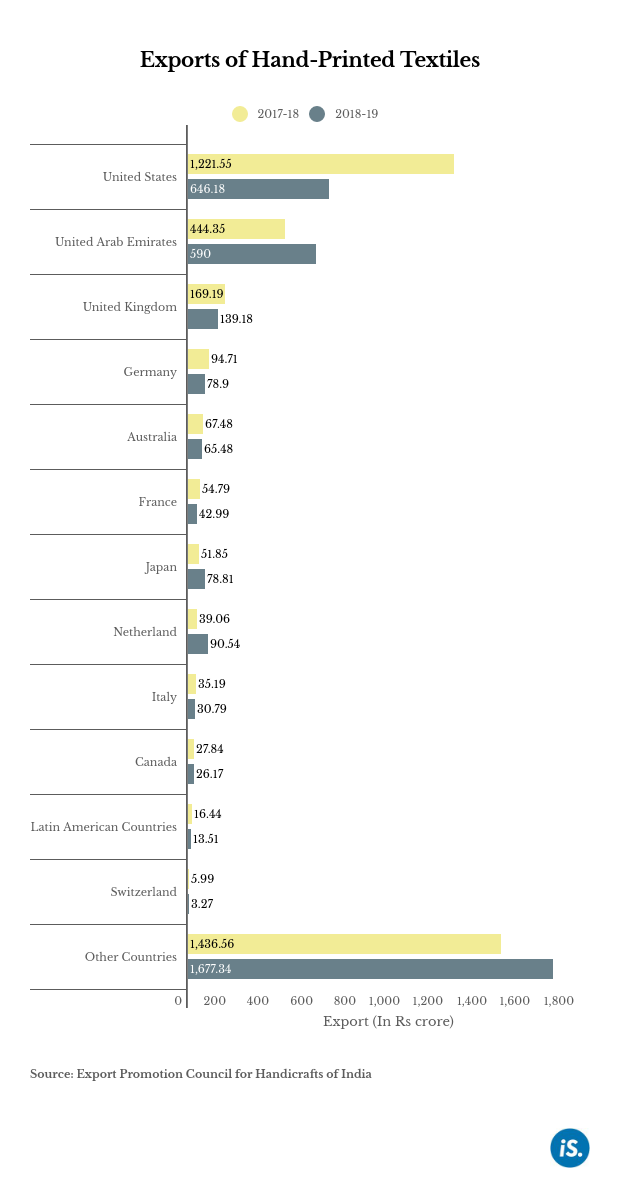

Countries such as the US, UK, Netherlands, Germany, France and Italy--most of them among the worst affected by the COVID-19 pandemic--accounted for 30% of the overall export of hand-printed textiles from India in 2018-19, reveal data released by the Export Promotion Council for Handicrafts.

The sector was trying to emerge from the aftereffects of the implementation of the Goods and Services Tax (GST) in India, when the pandemic struck--in the financial year 2018-19, exports had dipped 36% compared to the corresponding period of 2017-18 in the aforementioned countries due to the implementation of the Goods and Services Tax (GST) in India, said officials of the Jaipur-based Federation of Rajasthan Handicraft Exporters (Forhex).

“Because of the implementation of GST in mid-2017, the cost of handicraft textile manufacturing in India increased by 10%, and at the same time, Bangladesh made their products’ prices more competitive, which resulted in the foreign buyers choosing the latter over us,” said Atul Poddar, secretary, Poddar Associates, and a founding member of Forhex.

Changes in preferences

Together, Rajasthan’s exporters of hand-printed textiles say orders worth Rs 1,000 crore ($132 million), which were in production and ready to ship, have been cancelled for the months of March and April 2020. “Lot of orders were in the pipeline for which material had been procured and work was on. Even those orders have been withheld,” said Poddar. “We haven’t been given any commitment from the buyer on whether they will honor the order or not.”

Colour and material preferences in the textiles sector change with each season. “Textile manufacturing is a fashion-conscious industry that changes [its taste] every season, and a delay in shipment of items can lead to cancellation of orders by the buyers,” said Poddar, “The other challenge is that post-pandemic, people will go more for utility items rather than the luxury ones. So the product line will also change in the next six or seven months.”

“Americans generally prefer light and sombre colors,” he added. “However, with them stuck indoors for months to come, it will reflect on their preferences. They may go for bright and colorful textile now to lift their mood. Now, we have to make products in anticipation of the changed scenario, it is going to require an overhaul in production which is going to cost us more.”

The paying capacity of overseas buyers may also reduce for the short to medium term, exporters fear. “They are not in a position to pay us our dues right now,” Poddar said. “They are asking for more expandable delivery dates for the payment. They are asking for a payment date of upto 120 days. There is a possibility that even after 3-4 months they might just raise their hands and file for Chapter 11 bankruptcy. So we are in a very precarious situation.”

Machines used to wash and colour textiles (left) and tables where fabric is printed (right) lay idle in Sanganer, the hand-block printed textile hub outside Jaipur.

Restarting production

On the other hand, after four months of lockdown in developed countries, there might emerge a pent-up demand and buyers might go on a purchase spree. The coming four months, exporters say, are crucial.

The immediate challenge before the handicraft exporters now is to reboot the production process after the government lifts the lockdown next month, which is difficult given that there is no confirmation from buyers.

“Even if we try to start the production [for domestic buyers] the other challenge is how to stop the spread of coronavirus in our factories,” Vikas Singh, another Jaipur-based exporter, said, adding, “Our workers have left for their native places. Till they are sure that the production is starting on a permanent basis, they are not going to come back. So presently we are left with only 25-30% of workers who are staying near the factories right now.”

A deserted street in Tripolia, one of the main areas of Sanganer, where artisans live in rented accommodations.

Exporters have made representations to both the central and state governments to have all loan repayments (EMIs) deferred and interest waived. “Otherwise, employers will be left with no money to pay their workers’ salary,” said Brij Ballabh Udewal, owner of Shilpi Sansthan, a Sanganer-based NGO.

Meanwhile, for the daily-wage workers of the industry--who number among the 100,000 who earn their livelihood from it--the debilitating fear of having to sit out another month or two without any income is growing with each passing day. “I have nothing to fall back upon in case the crisis stretches,” said hand block printing worker Mohammad Khalil, who is from Uttar Pradeh’s Farrukhabad district and lives in Sanganer with his family of eight. “Even at my native place I don’t have any agricultural land. I have only learned this work to survive.”

Hope floats

Nevertheless, there might be some bright spots in the long run. Exporters are hopeful that post-pandemic, when the markets pick up, textile buyers and manufacturers might diversify away from China towards countries such as Vietnam, Bangladesh and India. Till then, however, half of the over 100,000 artisans stuck in Sanganer are in a dilemma whether to return to their native place or stay put in the hope that the work will resume and they could earn a living again.

(Bisht is a Delhi-based journalist. He writes on individuals, society and how the two interact and influence each other.)

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@indiaspend.org. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.