Can One More Scheme Improve Healthcare For Children?

The Government of India recently launched a new programme – Rashtriya Bal Swasthya Karyakram (RBSK) - under the National Health Mission (NHM) in February 2013 to focus on the health of school-going children.

The programme hopes to improve the quality of life of 270 million children with a focus on early detection of birth defects, diseases, deficiencies and disabilities (4Ds). The children will have access to public health facilities as well as facilities in their schools.

Interestingly, a similar programme –School Health Programme – is already operational under the National Health Mission itself. Started in 2008, the scheme covers around 1.29 million Government and aided schools and around 220 million students all over India.

It would thus appear that RBSK would pretty much mirror the SHM in its efforts. Which leads us to the larger question: is the multiplicity of schemes and their convergence defeating the very purpose of launching them? Particularly when both the centre and state are running similar initiatives. And the ultimate beneficiary is the same, in this case a child of 5-14 years.

Let’s see how many schemes target children in all? Quite a few, it would appear:

A few programmes with their 2013-14 budget allocations include:

* The Mid-Day Meal Scheme with an allocation of Rs 13,215 crore. It is the world’s largest school feeding programme providing meals to students and encouraging enrolment.

*Integrated Child Development Scheme (Rs 17,700 crore) providing immunisation, nutrition and health check-ups for children below 6 years; and

*Sabla Scheme, which got Rs 585 crore, to improve the health and nutritional status of adolescent girls (11-18 years)

These programmes total about Rs 31,500 crore, which is almost equal to the allotment to the Department of Health and Family Welfare in 2013-14(Rs 33,278 crore).

And yet, the numbers are scary. IndiaSpend has reported on the alarming status of child health in India. Government data shows, for instance, that in 2010, 2.7% of total deaths reported were of children in the 5-14 years group. Deaths per thousand for this age group are estimated to be 1% with the highest death rates observed in Jharkhand (1.4%), Orissa (1.3%) and Uttar Pradesh (1.3%). In addition, around 1.5 million children in India die before their 5th birthday every year.

Let’s return to the presently running School Health Programme (SHP). The programme includes health screening, remedial measures, health & nutrition education and nutritional intervention to ensure a healthy environment in school.

The funds for the SHP are channelled through the National Health Mission, which had a budget of Rs 18,515 crore in 2012-13. However, the utilisation of SHM funds is dismal. Between 2010-11 and 2012-13, the total amount approved was Rs 359 crore while the expenditure by the states amounted to only Rs 60 crore.

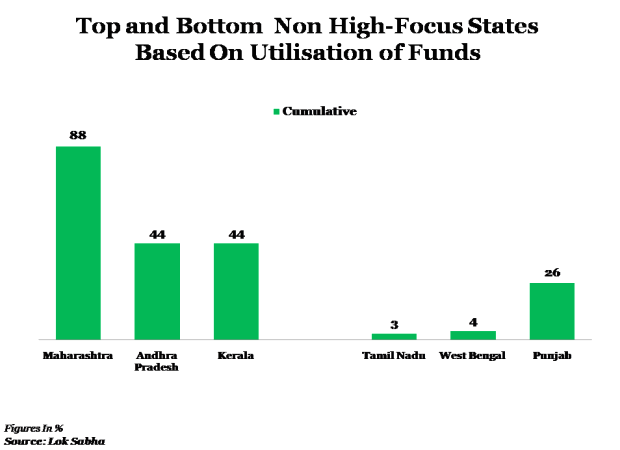

Significantly, there is a wide variation in states using its funds - Maharashtra utilises 88% of its allotted funds while Chhattisgarh and Uttar Pradesh utilise only 2% and 5%, respectively (data for last three years). Which also brings us back to the primary point. Schemes might be launched with good intent but run aground because of some failure in implementation by the states. To be fair, there might be good reasons for this too.

The SHP document of the Health Ministry says that it has been developed to provide uniformity to states already implementing their own programmes (Tamil Nadu and Gujarat are examples).

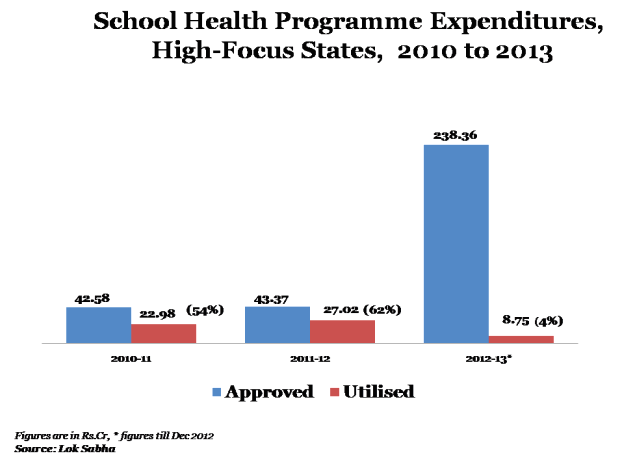

A Parliamentary reply last month said most states were lagging in expenditure under the School Health Programme. Figure 1 gives an idea of the funds released and utilised since 2010-11 to 2012-13 (as Dec, 2012) of the high-focus states (states with below average health indicators):

It is observed that the total approved funds for high-focus states since 2010-11 was Rs 324 crore while utilisation was only Rs 58 crore; i.e. utilisation of around 18% for the last 3 years. Interestingly, in 2010-11, the utilisation was around 54%, which increased to 62% in 2011-12 and plunged to 4% till December 2012.

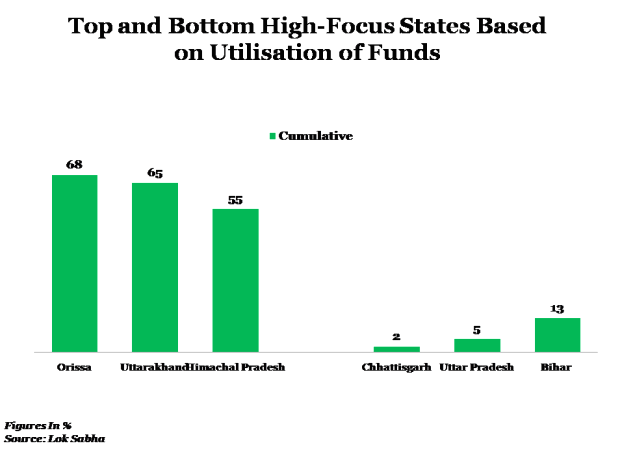

Figure 2 gives an idea of the high-focus states with the worst and the best utilisation percentage over the last 3 years:

It is seen that Chhattisgarh, Uttar Pradesh and Bihar bring down the utilisation percentage of the high-focus states while Orissa, Uttarakhand and Himachal Pradesh are doing well in utilising the money.

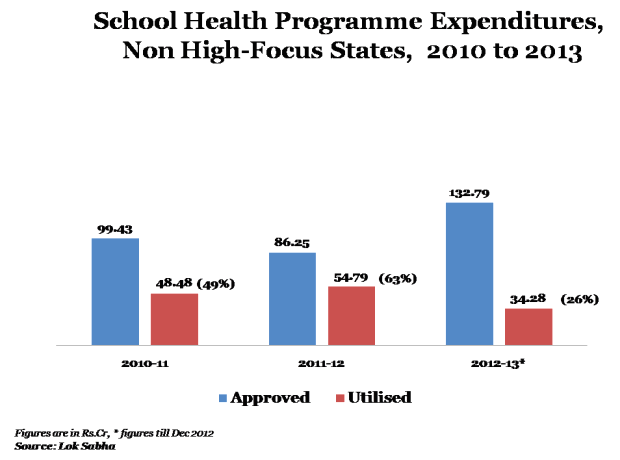

Figure 3 gives an idea of the utilisation rates of non-high focus states:

It is seen that the total approved funds for non high-focus states since 2010-11 has been Rs 318 crore while the utilisation has been Rs 137 crore, around 43%. The utilisation for 2010-11 was 49% which increased to around 64% during 2011-12, and is around 26% till December 2012-13.

Figure 4 gives an idea of the worst and best utilisation rates of non high-focus states:

It would appear that Tamil Nadu and West Bengal drive down the average badly while Maharashtra is doing well in utilising its funds for the school health programme.

The latest child health programme – RBSK – has also been set up to follow similar methods like regular screening of children in public health facilities. Whether the RBSK will actually improve child healthcare is one question. And whether people-oriented benefit schemes not working in tight harmony achieve their ultimate objective is the larger question.