Make Cooling Panels From Farm Waste Instead Of Burning It And Fouling Delhi Air: A Scientist’s Solution

Mount Abu, Rajasthan: November is when Delhi’s 16.3 million residents feel the worst effects of agricultural fires in Punjab and Haryana, crop stubble or waste set ablaze to clear land for the next crop. These fires cause about half of Delhi’s air pollution, according to a Harvard University study published in March 2018, not 20% as India’s former environment minister had claimed in 2017 (a scientist at the earth sciences ministry had estimated farm fires as contributing to 70%).

Now, Green Screen, a US start-up co-founded by Daniel Cusworth, one of the Harvard study’s co-authors, proposes a solution by converting the farm waste that is usually burned into cooling panels that can protect the poor in the Delhi urban agglomeration from extreme summer heat. The screens, expected to cost no more than Rs 350 ($5) per piece measuring just under one square metre--or about half the size of a standard door--will be made with a new material technology that involves using a natural binding agent, such as certain kinds of fungi, to convert crop stubble into a moldable substance.

India’s urban poor are among the most vulnerable people during the summer months, a season that is expected to gradually become longer, especially in the Gangetic plains, potentially peaking at eight months by the 2070s if greenhouse-gas emissions are not cut to limit the global temperature increase to 2°C, IndiaSpend reported in January 2018.

About a tenth of Delhi’s population lives in slums, according to the 2011 census. However, in 2012, the capital’s civic body estimated that nearly half its people lived in slums and unauthorised colonies devoid of civic amenities.

Air pollution--held responsible for one in every four deaths (24.4%) caused by non-communicable diseases in 2015--affects the poor and rich alike.

Last November, plumes of acrid smoke that drifted down to Delhi from the northern agricultural states were implicated in the rise in cases of severe breathlessness, asthma and allergy (see this report from 2017 and this from 2016). Growing pollution has also been implicated in the rising occurrence of non-communicable diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cancer and diabetes (see this 2017 global study published in the Lancet).

Green Screen hopes that its solution can offer some respite from the summer heat and help reduce air pollution. Cusworth, 30, an atmospheric chemist at the Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, said the “enormity” of Delhi’s air-pollution problem prompted him and his co-founders--Alex Robinson and Ramya Pinnamaneni, global health practitioners from the Harvard Chan Public Health School, and Gina Ciancone, an urban planner at the Harvard Graduate School of Design--to get directly involved.

“We are all interested in the intersection of human health and the environment, I am also interested in climate change and climate policy,” said Cusworth, a data scientist and applied mathematician. “What makes the issue of agricultural burning especially interesting is it is very complex due to the tradeoffs between air pollution, farming efficiency, and regulation.”

Yet, Cusworth has never visited India or experienced Delhi’s pollution.

“I’m prepping for my maiden visit,” he said. “I am really excited to experience India firsthand.”

Your study, published in the March 2018 issue of the journal Environmental Research Letters, concluded that about half of the air pollution observed in Delhi in the fall season could be attributed to agricultural fires. Since this research is your starting point for Green Screen, can you tell us how you arrived at this conclusion? Is the air pollution in other northern cities also caused by those fires?

We estimated that about half of the particulate pollution in Delhi during October-November was due to upwind agricultural fires. We came to this conclusion through two analyses. In the first analysis, we aggregated all particulate matter (PM 2.5) observations available from 2012-2016, which included the Central Pollution Control Board, the United States Embassy in Delhi, and your (IndiaSpend) own network. [In December 2015, IndiaSpend launched #Breathe, a network of low-cost sensors to measure the air quality in many Indian cities, including Delhi, based on the density of particles smaller than 2.5 microns, scientifically called PM 2.5.] We analysed the PM 2.5 concentrations in Delhi before and after fires to get a background estimate of the general state of pollution in Delhi. This background was about half the PM 2.5 observed during the fire events.

In the second analysis, we used satellite images of fire hotspots to derive PM 2.5 emission estimates of the regions upwind of Delhi. We combined these emissions with a fluid dynamics model to simulate the flow of this pollution towards the urban centre. The concentrations of this modelled PM 2.5 agreed with the observed PM 2.5 during most peak burning events. Again, we found about half of the pollution during these events was attributable to fires.

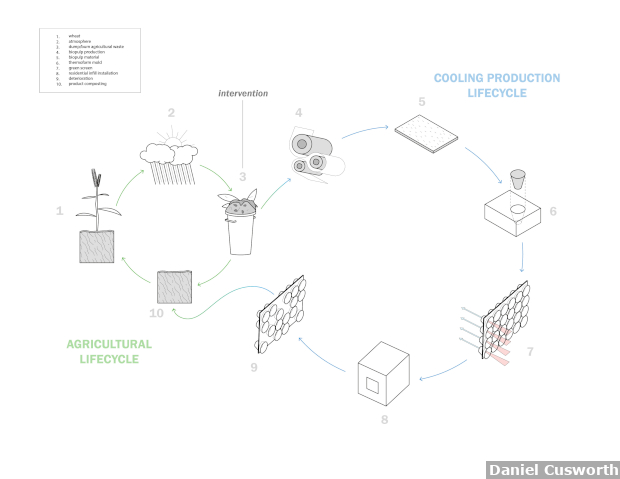

As you said, this research was the trigger for Green Screen. Quantifying the influence of upwind agricultural fire emissions on Delhi air pollution showed us the potential health benefits of changes in farming practices to reduce fires.

And to answer your other question, yes, the large quantity of smoke emitted by the agricultural fires also contribute to air pollution across other parts of the heavily populated Indo-Gangetic plain located downwind of the fires.

How did you move from your research to the concept of Green Screen, the portable, lightweight screen made of agricultural waste? Who conceptualised Green Screen? Can you describe the design of the screen? How much agricultural waste would you be using in the production of a screen?

Green Screen developed during a course at Harvard University, which aimed at creating viable solutions to intractable problems facing developing countries, such as India. Alongside Alex Robinson and Ramya Pinnamaneni, global health practitioners from the Harvard Chan Public Health School, and myself, Gina Ciancone, an urban planner at the Harvard Graduate School of Design led the development of Green Screen as a solution that could simultaneously address the interconnected problems of air pollution and extreme heat. Our team cuts across disciplines, as you can see.

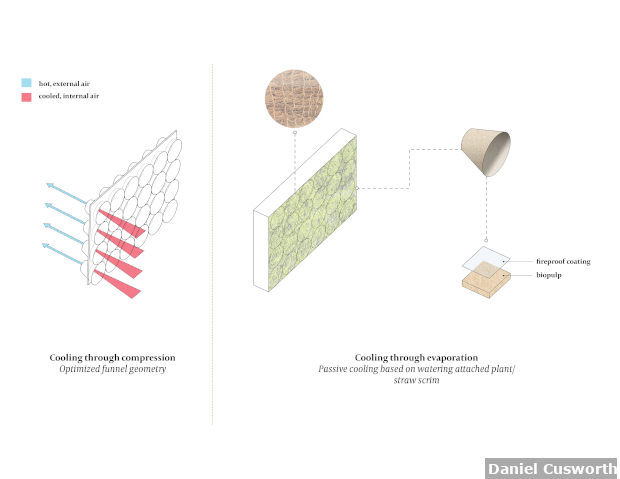

Green Screen is a zero-electricity consuming, air-cooling panel approximately 36” x 36” x 4” in size (but those dimensions may be adjusted based on the needs of the residential communities), made entirely of agricultural waste, which would have otherwise have been burned by farmers and further contributed to air pollution. Our solution simultaneously incentivises an alternative use for excess agricultural waste and transforms “waste” into a product used to cool those most at risk from extreme heat.

We will produce bio-pulp from the waste, and mould it into the conical-cooling geometry of the screens. The screen will cool through two processes--airflow and evaporation. If the panel isn’t watered, it will cool via the flow of air through the conical geometry. Using bio-pulp allows for watering which would further cool through evaporation.

Concept drawings of Green Screen.

Green Screen is designed to cover gaps and openings in incomplete structures, providing insulation and shade during the oppressive summer months. Since Green Screen is installed through a hinge system, it has the added benefits of functioning as a method of privacy and security for residents.

Although these are early days, we are considering potential design modifications, such as cowl, to adapt Green Screen for roof panelling. We will need to adjust the size of the panelling and test it for load-bearing and durability to determine its potential to replace larger portions of the structure.

While the exact amount of agricultural waste needed to optimise the impact of Green Screen is still being determined, early projections aim to produce 100 screens from one tonne of bio-pulp, which would prevent one tonne of carbon dioxide from entering the air. To give you some perspective on the pollution saving, a typical passenger vehicle emits about 4.6 metric tonnes of carbon dioxide per year.

What happens next? Do you have a product ready to launch in India?

We have had early prototypes of Green Screen fabricated from materials sourced in the USA to test the geometry of the product. Obviously, we want to develop an optimised product, this involves getting the size of the conical shape right.

Next, our partners, two not-for-profits, the Delhi-based Chintan and the UK-based WIEGO, will work with us to install (for free) and test the effect of these screens at the household level within specific slums in New Delhi. This will enable us to better determine product suitability, feasibility and usefulness. This will occur during the product’s pilot phase in 2019. We are currently developing a deployment strategy with our partners.

While all this is going on, we plan to enlist a domestic team in order to better coordinate all the prototyping and piloting efforts. Our goal is to manufacture and produce the screens in as close proximity to Delhi as possible to minimise outsourcing.

Eventually, obviously Green Screen will be sold. We aim to produce an affordable product. Our goal is to sell Green Screen products for less than 1% the cost of a conventional air conditioner, no more than Rs 350 ($5) per screen.

I say products because the plan is to scale up and diversify Green Screen production in future to include ventilated portable tents for day labourers and small-scale buildings.

You have modelled how the smoke and pollution generated in Punjab and Haryana would be impacted if farms in different regions did not burn their stubble, to pinpoint which farms you should target to procure agricultural waste for production. Were these farms in any particular area of Punjab or nearer Delhi?

We will be sourcing the agricultural stubble from farms outside of New Delhi for the next phase of development happening later this year. We are working with Chintan to determine the location of agricultural farms with which to coordinate. The exact farms and locations have not been finalised.

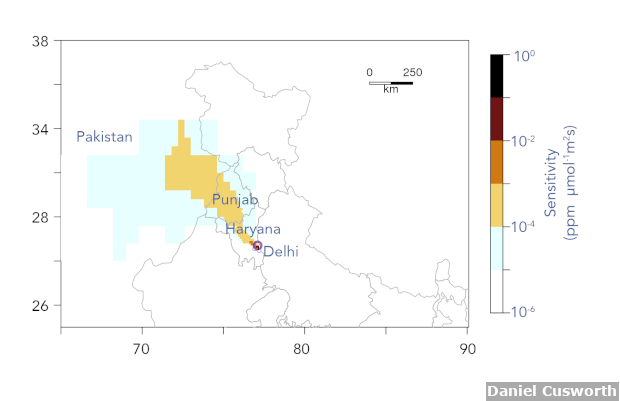

Actually, this is an ongoing project of ours to pinpoint which farms have the largest potential air quality benefit, and then to use that information to form partnerships with farmers. We can’t comment yet about specific farms, but below is a figure from my recent paper that shows the median 2012-2016 sensitivity of urban pollution in Delhi to upwind fire emissions. From a map such as this, you can deduce which regions (darkest colours) would influence pollution in Delhi the most.

Sensitivity Of Urban Pollution In Delhi To Upwind Fire Emissions

Do you anticipate any challenges? Are you looking for government support?

While challenges are always part of the development process, we are confident that the variety of skill sets within the Green Screen team will convert these challenges into unforeseen opportunities that will ultimately lead to a better product. We look forward to cooperating closely with the Delhi Pollution Control Committee, Environment Department, and relevant municipal authorities to ensure our targets are in line with broader, ongoing “greening” efforts in the city.

(Bahri is a freelance writer and editor based in Mount Abu, Rajasthan.)

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@indiaspend.org. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.