Manipulative Fake News On The Rise In India Under Lockdown: Study

Mumbai: A team of doctors, health workers and revenue officials who had gone to identify the family members of a 65-year-old man who died of COVID-19 were attacked in Indore, Madhya Pradesh, on April 2, after fake videos claimed that healthy Muslims were being taken away and injected with the virus, reiterating the dangers and physical manifestations of misinformation.

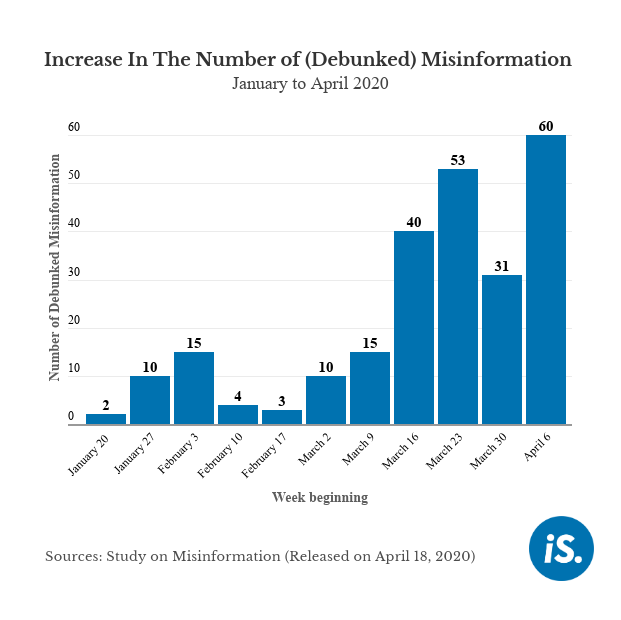

A study on misinformation in India by scholars from the University of Michigan, released on April 18, 2020, has shown a rise in the number of debunked stories, particularly after the announcement of janata curfew by Prime Minister Narendra Modi on March 22, 2020, and the countrywide lockdown two days later, to contain the spread of COVID-19.

From just two in the third week of January 2020, the instances of debunked misinformation rose to 60 by the first week of April 2020, according to the study. Though fake stories around a cure for COVID-19 lessened in this period, false claims that affected people emotionally increased, the study found.

The study used 243 unique instances of misinformation from an archive maintained by Tattle Civic Technology (a Delhi-based news project that aims to make accurate information more accessible to mobile-first users). The archive represents all the stories that have been debunked by six fact-checkers--AltNews, BOOMlive, Factly, IndiaToday Fact Check, Quint Webqoof, and NewsMobile Fact Checker--certified by International Fact-Checkers Network (IFCN) between January 23 and April 12, 2020.

The momentum of misinformation was already building up before PM Modi’s announcement of the janata curfew, but there was a consistent rise in the number of debunked fake news, following the third week of March 2020, the study found.

The misinformation that was circulating on various social-media apps, as found by the study, was classified into seven categories--culture, government, doctored statistics, etc. About 62 fake stories were related to culture, defined as messages targeting a particular socio-religious, ethnic group, followed by 54 instances of fake news around government announcements and advisories, according to the study.

| Types of Misinformation | ||

|---|---|---|

| Category | Instances | Definition |

| Culture | 62 | Messages with cultural references such as to a religious / ethnic / social group or a popular culture reference |

| Cure, Prevention & Treatment | 37 | Messages suggesting remedies (alternative or mainstream), preventive measures, and vaccines-related misinformation |

| Nature & the Environment | 16 | Messages that have references to animals and the environment. |

| Casualty | 36 | Messages relating to deaths, illness of people in the pandemic, including graphic images of suffering (not including doctored statistics) |

| Business and economy | 15 | Messages relating to scams, panic-buying and target businesses with fake positive cases. |

| Government | 54 | Messages have government announcements and advisories or refer to police, judiciary, political parties. |

| Doctored statistics | 23 | Messages that have exaggerated numbers of positive cases or death counts and fake advisories. |

Source: Study on Misinformation (released on April 18, 2020)

Manipulation by misinformation

Two categories of misinformation that caught the eye of the researchers due to their consistent rise were stories around culture and government. This pattern emerged with a visible increase in stories around Muslims and COVID-19 as well as stories around police brutality. By the end of March 2020, the number of fake stories increased from 15 in the week beginning March 16 to 33 in the week beginning March 30, with the Tablighi Jamaat event at Nizamuddin Markaz in Delhi being highlighted as a vector of novel coronavirus, according to media reports.

In contrast, the number of fake stories around casualty--fear-evoking messages related to deaths, suicides and suffering of people in the pandemic or graphic imagery--and COVID-19 cure peaked and fell from 18 in number to 12 during the same period, the study found.

“Post the Tablighi Jamaat incident, we saw a change in the tone of fake news--focussing on a particular community that was being targeted as the ‘super spreader’,” said Jency Jacob, editor of Boom News, a Mumbai-based initiative that busts fake news. “When it comes to communal posts, only text does not create the sort of required emotional connect with the viewer. And, lay people cannot really figure out whether a video clip is new or old. In contrast, posts about cures, say drinking lemon water, don’t really need an image for me to believe it.”

High on emotions, low on facts

India is entering a phase in misinformation which is intended to be affective around identity and emotion rather than instrumental facts that can be scientifically verified, the study said. Thus, from presenting fake cures or fake images of pain--which, over time, get debunked or appear suspicious to viewers--the misinformation has moved to cultural elements that are harder to verify.

“There are many reasons; one is pure mischief, people who enjoy seeing falsehoods--they create, propagate,” said Joyojeet Pal, one of the authors of the study. “Another reason is political; driven by those who want a certain agenda to prevail. And then, there is pure economics, on platforms where you can monetise virality (say YouTube), you can make money out of click-baiting people; the more extreme and controversial a piece of fake news sounds, the more likely it is that someone will click on it.”

How the universe of misinformation works

Different modes of media are used to relay different kinds of misinformation, shows the study. For example, misinformation in the ‘casualty’ category relies heavily on visual content, such as video clips, since the goal is to evoke a physical reaction, often fear or disgust. On the other hand, tweets on the so-called cures and misleading statistics use a lot of text because the aim is to mislead by offering specifics, the study noted.

“People have more time now and often misinformation comes with an agenda,” said Jatin Gandhi, fact-checking trainer and journalism educator. “During a pandemic there is anxiety and fear of the unknown which creates favourable conditions for spreading misinformation. It is also used as a diversion from real issues, such as failure of governance or the fact that there is no cure yet for the disease.”

The study also found that content categorised as ‘culture’ or ‘casualty’ is, in all likelihood, repurposed old content to suit the current discourse. Since both these categories seek to affect the viewer emotionally, the creators of such content often seek out explicit content and repurpose it with a false heading since it is likely to have greater shock value, the authors wrote.

Mainstream media’s complicity

Several mainstream media houses, including newspapers and news channels, have put out widely circulated misinformation, showed the study. Even public figures, by not removing the debunked misinformation, have contributed to the propagation of false information. For instance, businesswoman Kiran Mazumdar-Shaw tweeted that countries in the southern hemisphere remain unaffected by the coronavirus outbreak; her engagement with it gave the idea some credence and led to widespread engagement online before and after it was debunked by Alt News.

Though the study could not cite clear reasons as to why mainstream media was sharing misinformation, it hinted that some may simply be out of poor editorial standards in a highly competitive media ecosystem. “One thing that remains clear, however, is that misinformation travels fast,” the authors wrote, “and that news sources may increase footfalls through deliberate misinformation or click-bait headlines.” In such a scenario, “mainstream news sources have been particularly complicit in Muslim-baiting”.

(Salve is an IndiaSpend contributor. Editing by Pooja Vashisht Alexander.)

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@indiaspend.org. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.