Mobile Medical Units Can Improve Access To Quality Healthcare, If Funded Well

Bilaspur, Hamirpur, Mandi, Shimla and Solan: In a 225-sq ft room that just about fits a bed, 72-year-old Rinjhin downed a cup of tea prepared on a small kerosene stove and accompanied her husband to a blue bus parked 300 metres downhill from her home in Barog village in Himachal Pradesh’s Solan district.

As Rinjhin looked for a seat to rest her aching body in a nearby tin shed, her husband, Baatir Singh, 73, joined a queue of about 15 people, mostly elderly, waiting for their turn to see the doctor. This had been their ritual every Thursday morning for the past two years.

This was not a primary healthcare centre (PHC) or a hospital, but a mobile healthcare unit set up on a bus, complete with a doctor, a pharmacist, a laboratory technician and a physiotherapist.

One of 11 operated by the charity Helpage India in the state, this mobile healthcare unit provides free consultations, essential medicines, some pathological tests and physiotherapy. There are 26 such mobile medical units in the state, all operated by nonprofits, some part-funded by the government.

Singh and his wife have joint- and back-aches that make it difficult for them to travel to the hospital, an hour from their home. “This facility has greatly benefited me and my wife,” Singh said.

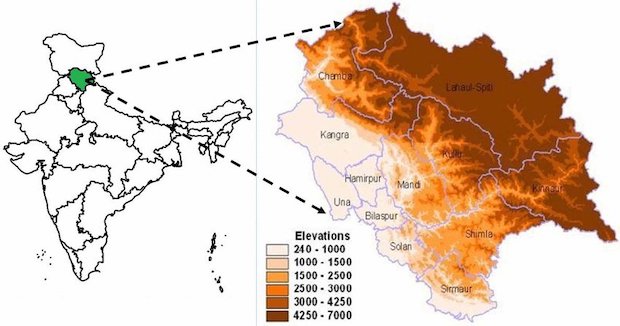

In the hilly regions of Himachal Pradesh, where narrow roads make their way through lush forests, even short distances take long to traverse. It is often difficult for the sick and the aged to travel to PHCs. Sometimes, when they do visit a PHC, there is no doctor or other facilities are missing.

The National Health Mission (NHM) introduced Mobile Medical Units (MMUs) to bring healthcare facilities to those living in remote and underserved areas. There should be at least one MMU in each district, and a maximum of five, NHM guidelines said.

Although MMUs are particularly needed in hilly, remote areas, the north-Indian Himalayan states have the fewest, government data from March 2018, the latest available, show. Of a total of 1,427 MMUs in India, nearly a third (415) were in Tamil Nadu, followed by Rajasthan (206), Madhya Pradesh (144) and Assam (130). India’s most populous state, Uttar Pradesh, and the hill states of Uttarakhand and Tripura, had none. Arunachal Pradesh and Nagaland had 16 and 11, respectively.

Himachal Pradesh, by comparison, has 26 across nine of its 12 districts, though only 15 are recognised as MMUs--HelpAge India’s 11 units are registered as ‘clinics’ under the Clinical Establishments Act, hence not officially recognised as MMUs.

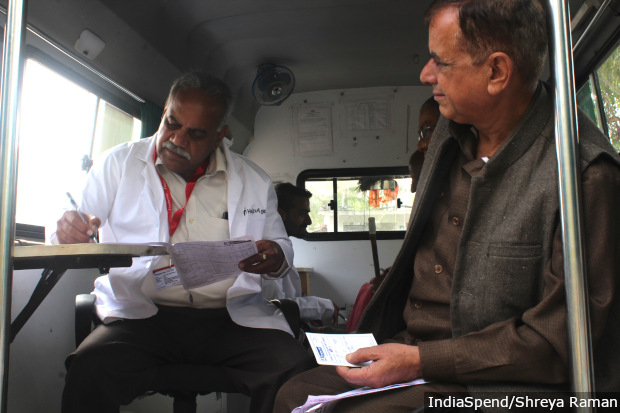

Diwinder Singh Balluria, a doctor, conducts a check-up inside a Mobile Medical Unit operated by Helpage India in Kalihatti, Shimla, October 25, 2019.

MMUs attract a steady stream of patients wherever they set up for the day, as we found during our visit across five districts in October 2019. Visitors said they were happy to get checkups as well as medicines at their doorsteps, though in many cases people traveled to visit them from far, saying they found MMUs more reliable than the PHCs closer home.

However, the quality of care varied between MMUs, we found, mostly depending on funding. For instance, some units were equipped with advanced diagnostic equipment, while others did not even employ a qualified doctor.

Public health centres

India ranked 145th among 195 countries in terms of healthcare access and quality, as IndiaSpend reported on May 23, 2018. PHCs, the first point of access to doctors in the public healthcare system, are especially overburdened.

In 2018, one PHC covered, on average, 32,387 people, though the Indian Public Health Standards recommend one PHC for 30,000 people in the plains and one for 20,000 in hilly areas such as Himachal Pradesh.

Himachal has more PHCs than the Indian average--each PHC serves about 11,000--but these PHCs are often understaffed, and an inadequate road network affects access for general and emergency medical care.

Some 18.6% of PHCs in the state did not have doctors, 84.7% did not have laboratory technicians, and 45.3% did not have pharmacists, the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MOHFW) told the lower house of the parliament, the Lok Sabha, in July 2019.

Across India, one-third (34.5%) of PHCs did not have lab technicians and 15.6% did not have pharmacists, according to the same Lok Sabha response.

MMU funding

Pharmacist Amit Kainthla at an MMU in Kalihatti, Shimla, dispensing medicines on October 25, 2019.

As per NHM guidelines, the government can fully own and operate MMUs or provide the capital expenditure. It must also provide drugs and other supplies.

In Himachal Pradesh, all the 26 MMUs are run by nonprofits.

Paryas Society, a Hamirpur-based NGO, runs 15 MMUs in the four districts of Hamirpur, Una, Bilaspur and Mandi. The cost of the van and equipment for 17 units came from the Members of Parliament (MP) Local Area Development Fund--which provides Rs 5 crore per year to every MP for their five-year tenure--of the local MP, Anurag Thakur.

The operational cost of three units is supported through the NHM. Four to five companies cover the cost of 12 MMUs under their Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) obligations. Two MMUs are not currently operational.

The MMUs run by Paryas Society have a budget of about Rs 12 lakh each per year, Vikas Singh, the doctor in-charge of the MMU programme at Paryas told IndiaSpend. This is 57% lower than the NHM-recommended Rs 28 lakh per unit. The government contributed a total of Rs 10.7 lakh in the financial year 2018-19 for three units, said Archana Soni, chief medical officer of Hamirpur district. This is less than a third of the amount required to run these units, as per the Paryas’ budget.

The NHM recommends equipment such as an electrocardiogram machine, a refrigerator and a steriliser. Paryas MMUs do not have these services.

When asked if the allocated funds were sufficient for the functioning of MMUs as per NHM specifications, state NHM officials said they did not want to comment.

To run an MMU on a lower budget and because of the dearth of doctors with a Bachelors of Medicine And Bachelors Of Surgery (MBBS) degree in the hilly region, Paryas hires Ayurvedic, Unani, Siddha and Homeopathy (AYUSH) doctors, who are not qualified to practice modern medicine as per the Indian Medical Council Act, instead of hiring doctors with an MBBS degree.

Vikas Singh, the doctor who heads the operations of the Mobile Medical Units at Paryas Society, says that it is not possible to hire MBBS doctors in all units within the current budget.

“No MBBS doctor agrees to a salary of less than Rs 1 lakh a month,” said Vikas Singh, “So it is practically impossible to have MBBS doctors in all the units. We have hired an MBBS doctor per district to oversee the operations.”

“It can be Rs 80,000 or Rs 90,000 per month or even more if they are deployed in tribal or extremely remote areas,” said Rajesh Kumar, Himachal Pradesh head for HelpAge India.

HelpAge India runs 144 such units across 24 states in India, and 11 across seven districts in Himachal Pradesh.

HelpAge India’s budget is twice that of Paryas Society’s, but it still does not provide all the NHM recommended facilities. On average, the charity spends Rs 30 lakh per unit per year, and has an MBBS doctor, a registered pharmacist, a lab technician and a driver. These units have basic medicines, and can check blood pressure and blood sugar.

The units run by Paryas provide more pathological tests than the HelpAge India units and include tests for cholesterol, liver and kidney function.

There are some MMUs that have much higher budgets. The HelpAge MMU in Solan that Rinjhin and her husband visit, for instance, has a budget of Rs 1.3 crore for a period of three years and an annual operating cost of Rs 45 lakh. This unit can conduct most urine and blood tests, and even hold physiotherapy sessions.

Need for regular visits

Gulabo Ram, 86, is diabetic and lives alone in Takrera village of Himachal Pradesh. A Mobile Medical Unit operated by Paryas Society came to his village and provided him with a free check-up and medicines for seven days. He wishes the unit would visit more frequently so that he would not have to travel to the hospital 3 km away 2-3 times a month to fetch his medicines.

On October 22, 2019, a team from the NGO Paryas carried a suitcase and walked to the Takrera village anganwadi (childcare centre) in Himachal Pradesh’s Bilaspur district. In the suitcase was equipment for conducting blood tests. That day, 44 patients came to the mobile health centre.

“We try to set the camp as close to the village centre and in a community building like anganwadis or schools. It is more accessible and comfortable for the patients,” said Ankita Sharma, the doctor-in-charge at the Takrera camp.

Such units could be especially helpful to the elderly who live alone, like Gulabo Ram, 86, who has been diabetic for over 15 years. His wife passed away 20 years ago. His daughters are married and live away, and he is not on talking terms with his son, he said. “I have to go to the hospital 3 km away, alone, 2-3 times a month. It becomes difficult,” he said, leaning on his walking stick. Free medicines are given only for seven or 14 days at a time, he said.

The Paryas team gave Gulabo Ram medicines for seven days, after which he will have to visit a hospital. Gulabo Ram said he wished the mobile unit would visit more frequently so that he could avoid travelling to the hospital.

The Paryas MMU will visit this village after 1.5-2 months, after it has visited all the remaining villages in the assembly constituency of Ghumarwin. Doctors on the team said it can take 4-6 months to revisit a village.

As per the NHM guidelines, the units should frequent an area at least once a month and the deployment should be prioritised in areas with no functional facilities.

Nirmala Devi, 70, travels 13 km to reach a mobile healthcare unit in Barog, Solan district, Himachal Pradesh. She finds the camp more reliable than the government primary health centre where the doctor is available only on some days and does not keep fixed timings.

HelpAge India targets villages identified as having poor health infrastructure or being backward through a baseline survey. “MMUs visit 5-12 of these villages consistently on the same day each week,” said Manoj Verma, social protection officer at HelpAge India’s Solan unit. “This helps us build trust within the community.”

In Barog in Solan district, close to 70% of the patients at the HelpAge India unit the day IndiaSpend visited had come for follow-ups, and had been visiting the camp for longer than a year, they said.

Nirmala Devi, 70, had been a regular for two years, visiting for diabetes treatment, even though her village is 13 km from the clinic. The PHC is 1 km away from her house but “the doctor is present at the PHC only on Wednesdays and that too for a few hours, which are not fixed”, she told IndiaSpend. “Coming here is better than walking to the PHC and coming back with no check-up and medicines.”

All Mobile Medical Units operated by Paryas Society have a laboratory kit that fits in a suitcase. This makes it portable, enabling the staff to carry it even to the most remote villages.

Remote districts at higher altitudes have fewer MMUs

As many as 22 of Himachal’s 26 MMUs are in low-lying areas. Four HelpAge India MMUs--in Kinnaur and Kullu--are in districts at higher altitudes.

“It is more difficult to operate a medical unit in areas with higher elevation,” said Rajesh Kumar from HelpAge India. “It is difficult to find staff there, it is difficult to navigate the roads there and during some days in the winter we might have to stop the operation altogether.”

Source: Seasonal and annual rainfall trends in Himachal Pradesh during 1951-2005

The remaining districts, mostly at higher elevations where PHCs are more difficult to reach for sick or aged people, will get government-run MMUs by 2020, Nipun Jindal, mission director of NHM, Himachal Pradesh, told IndiaSpend. The state NHM team has been trying to get such units operational for 13 years, but there has not been adequate response to the issued tenders, he said, adding, “However, by January 2020, we hope to get mobile health and wellness centres operational in all the districts of the state under the new Jeevan Dhara scheme.” The state scheme aims to set up mobile health and wellness centres in each district to dispense free medicines and conduct up to 50 types of tests.

Mobile units set up under this scheme will have an MBBS doctor and will follow the NHM guidelines, Jindal said. He added, however, that the government’s thrust is on improving PHCs. “In the end, Mobile Medical Units are a secondary service that we can provide to the citizens,” he said. “Our primary objective is to ensure that the primary health centres are well-equipped and operational.”

Until that objective is met, Baatir Singh counts on the MMU in Barog that he visits every Thursday. Singh, who had worked as a daily wage labourer since 1970, said he stopped working in 2000 after a botched-up surgery led to an infection and four surgeries.

“I have no energy left to work or to travel to the hospital, which is an hour away,” said Singh, “I am happy that I get such a facility so close to our home.”

(Shreya Raman is a data analyst at IndiaSpend.)

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@indiaspend.org. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.