No Cure Or Vaccine, Doctors Rely On Each Other, & Guidelines

Mumbai & Jaipur: “We were all really scared,” said Jeenam Shah, a pulmonologist, of the time his first COVID-19 patient arrived at South Mumbai’s Wockhardt Hospital, on March 24, 2020. “This was the first case, no one [knew] what [was] going to happen, including me,” Shah told IndiaSpend, “We were all scared about how to deal with this.”

With no cure available yet for the highly infectious COVID-19 and a vaccine that is at least 12-19 months away, frontline healthcare staff are working without established treatment protocols, unlike for most other diseases. They must rely on the general guidelines offered by health and research bodies, and feedback from each other.

With patchy evidence on the efficacy of the drugs being used, doctors told us they use a range of options that include basic symptomatic treatment, antimalarial and antiretroviral drugs, swine flu medication, and at times, a cocktail of drugs.

No proven treatment

There is “no cure or treatment” for COVID-19, the World Health Organization has said, but has offered guidelines for its management. “No specific antivirals have been proven to be effective as per currently available data,” stated the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), in its Revised Guidelines on Clinical Management for COVID-19, released on March 31, 2020.

“We are following the WHO and ICMR guidelines for treatment,” said Ravikant Singh, a public health expert and founder of Doctors for You (DFY), a nonprofit working with governments in Bihar and Maharashtra to provide care for COVID-19 patients.

For in-patients who are severely affected and need intensive care, doctors can prescribe the off-label use of two existing medicines under close medical supervision: hydroxychloroquine (HCQ), used for treating malaria, rheumatoid arthritis and lupus, and azithromycin, an antibiotic, as per the ICMR guidelines.

“There were [a] few reports published to show some efficacy [of HCQ] but the data generated through those studies was not very sound to support the use of HCQ,” said Sunit K Singh, virologist and head of the Molecular Biology Unit at Banaras Hindu University (BHU).

IndiaSpend had earlier reported that there was insufficient evidence of the effectiveness of HCQ as a preventive or cure for COVID-19. The major evidence on the efficacy of HCQ came from a French study that “did not meet the expected standard” for publishing, as Retraction Watch--a website that tracks published studies--said on April 3, 2020, quoting the society that publishes the scientific journal where the study had first appeared. It is the same drug that the US, with the world’s highest number of COVID-19 patients, asked India to supply, and India said it had allowed companies to export the drug to other countries as there is sufficient stock for Indian patients.

Doctors use a combination of drugs

With no set protocol in place, doctors are relying on their peers for consistent feedback, we found. “We have team meetings and discuss with our teams in other states about the treatment plan and new observations,” said Ravikant of DFY.

For cases in which the patient is asymptomatic or has mild symptoms, doctors who spoke to IndiaSpend said they prescribe multivitamins, or medicines for relief. About 80% of COVID-19 patients are likely to have mild to moderate symptoms such as cough, sore throat, muscle pain and fatigue, according to a February 2020 WHO-China joint monitoring report, which analysed 55,924 confirmed COVID-19 cases.

Around 13.8% of patients could develop severe symptoms and 6.1% of cases would progress to the critical stage, said the report.

"But that doesn’t mean that the 80% [with mild symptoms] don’t require anything,” said Ravi Dosi, head of the chest division at Indore’s Sri Aurobindo Institute of Medical Science (SAIMS), which has over 100 COVID-19 patients. “We constantly monitor them and take care of them.”

There are two schools of thought on the treatment, said pulmonologist Shah. “The recommendation worldwide is to not give any medicines to those who are asymptomatic, but in India, in the beginning, we were giving HCQ and azithromycin even to patients who were asymptomatic or had mild symptoms,” he said.

“Our thinking was better to give whatever we have, rather than wait for the symptoms to increase,” said Shah, who had prescribed this line of treatment to his patients.

For moderate symptoms, doctors usually prescribe azithromycin or broad spectrum antibiotics, with or without HCQ, depending on the patients’ symptoms, doctors said. Those with severe symptoms are prescribed a combination of HCQ, azithromycin and oseltamivir, a swine flu medication.

Swine flu medication is given only when the patient is running a high fever, Shah said.

Some doctors are also experimenting with a cocktail of other drugs, including antiretroviral drugs used for the treatment of HIV, Ravikant of DFU added. Preliminary evidence suggests that some antiretrovirals might not be effective in fighting COVID-19.

Testing, hospital admission

Diya Naidu, 36, a performer and choreographer, who returned to Bengaluru from Switzerland on March 8, 2020, spoke to IndiaSpend about her experience of the disease. She had no symptoms when she was screened at the airport but started feeling lethargic two days after her return. In the following days, she lost her sense of smell and taste.

Naidu, who went to see a private doctor, was denied a test--at the time, India was testing only symptomatic travellers returning from a select group of countries that included Italy, China and Singapore. Naidu tested positive on March 16, 2020, when the testing criteria was expanded to include more countries, including Switzerland.

Diya Naidu, 36, praised officials in Bengaluru for tracking down all her primary and secondary contacts as well as conducting random testing in homes within 5 km of hers.

An ambulance picked her up from her home to take her to a government facility and several officials started reaching out to her--this included state disease surveillance officials, police officials, regional medical officials and Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike (BBMP) officials. “It was difficult to know who was in-charge,” said Naidu, adding that she was overwhelmed with the effort government officials put in. “Where the systems fail, humans make up.”

Bengaluru officials traced 16 of Naidu’s primary contacts as well as all their contacts, and conducted random testing of those living within a 5-km radius of her home. Nurses accompanied officials to the homes of her primary contacts to check for symptoms, said Naidu.

“I have lost count of how many tests were done but even after I tested negative, the test was repeated two times to be sure,” said Naidu. When she tested negative, she was moved to another ward with a patient who had also tested negative. She was discharged on April 6, 2020, after three negative tests.

Isolation frustration

When suspected or confirmed COVID-19 patients come in, doctors stick to the routine: Check vitals, order tests and check their oxygen saturation levels, said Ravikant of DFU.

Currently, India is isolating all suspected patients, patients with symptoms as well as confirmed cases that are asymptomatic; they are isolated in separate wards in the same hospital, or in different hospitals or care centres, until they test negative in consecutive tests. This means no visitors are allowed and patients, including those with no symptoms, cannot leave their wards.

There were about 30 patients in one ward in Indore’s Sri Aurobindo Institute of Medical Science, all of whom had mild to moderate symptoms, Sumer Singh, a patient who tested positive for COVID-19 on March 26, 2020, told IndiaSpend. The beds were five feet apart, people would chit-chat and walk around their beds to pass the time, said Sumer, who is a ward boy from a private hospital and had contracted the infection from a patient. Doctors would visit around three times a day and all healthcare workers wore protective gear, he added. Sumer tested negative in two tests and was discharged from hospital on April 10, 2020.

“The problem with asymptomatic patients is that they do not understand why they have to be in the hospital in isolation,” said pulmonologist Shah. Sometimes, “these patients are kept in an ICU [intensive care unit] which is usually dark; they have to use a single washroom, no relatives are allowed of course, so they have psychological changes [problems], they get frustrated”, he explained, highlighting the mental health issues isolation could cause.

Very few patients need a ventilator, elderly more vulnerable

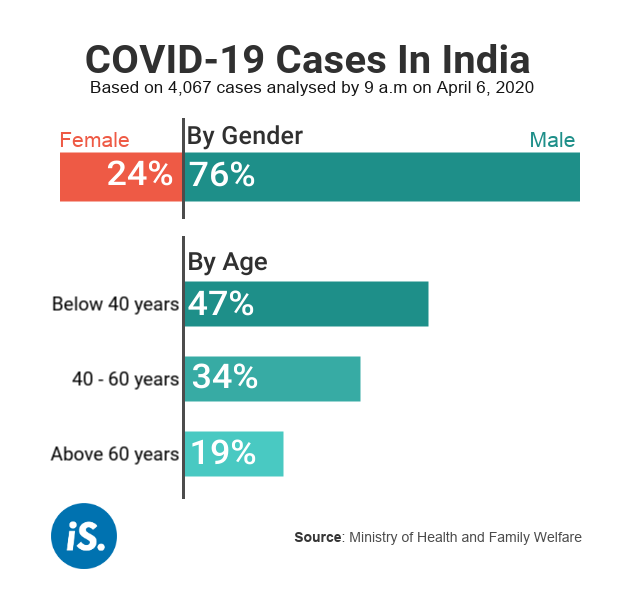

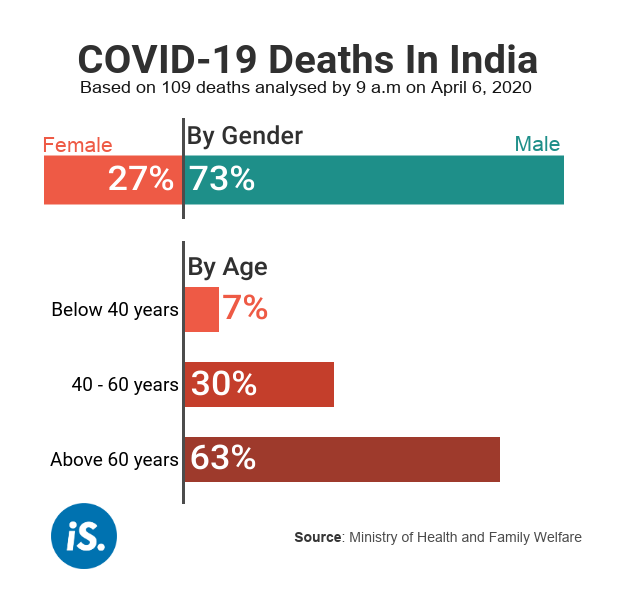

As of April 6, 2020, 47% of India’s COVID-19 patients were under 40 years of age while 19% were older than 60 years, said Lav Agarwal, joint secretary at the health ministry, during a press conference. Still, of the 109 deaths until April 6, 2019, 63% have been among the elderly, as IndiaSpend reported on April 6, 2020.

India is not releasing data on the demographics of patients regularly, but provides them occasionally.

Across the world, 18.4% or nearly two in every five patients over the age of 80 will need specialised care in a hospital, according to this Lancet study.

Diabetics, and those suffering from underlying diseases of the heart, kidneys and lungs, are also at a higher risk of developing severe symptoms, said Singh of BHU. Data from India show that 86% of the deaths until April 6, 2020, were among patients with comorbidities.

“If a patient is elderly and has a lot of comorbidities, we do not recommend very aggressive treatment, such as going for ventilator support, bronchoscopy and other invasive procedures,” said Shah. We discuss with the family and ask the question: “If the patient recovers, what will be the quality of his life?”

In the case of one acutely ill, elderly patient whom Shah treated, the family decided against deploying the ventilator because of the poor quality of life he would have had even if he had recovered, the doctor said.

“What is needed is early referral of the patient,” Salil Bhargava, a professor and doctor at a COVID-19 facility in Indore, told IndiaSpend. “If cases come to us early, there is less probability of the disease becoming serious.” Most deaths occur when patients come too late and already have widespread pneumonia in both the lungs and acute respiratory distress syndrome, he added.

Stigma too gets in the way of treatment, said Ravikant of DFU, with neighbours and close circles treating COVID-19 patients and their family poorly even after they have recovered or completed the quarantine requirement, as IndiaSpend reported earlier from Bihar.

Tough environment for healthcare staff

It is not just patients but doctors, nurses and supportive healthcare workers who operate in a difficult and stressful environment, we found. They also have to make tough personal choices. “Because I live with parents and my father has several pre-existing conditions including diabetes and hypertension, I was asking myself if I should treat these patients or protect my family from getting infected,” Shah said.

Sumer, the Indore patient who worked as a ward boy, caught the disease from another patient who had come to the hospital. “When she came in, no one knew she was a coronavirus case,” he said. “We thought it was a usual hospital case.” The patient had been in the ICU where he was posted for two hours before the doctors suspected that it could be COVID-19. When she was moved to the isolation ward as a COVID-19 suspect, Sumer helped set her up with the monitor. He was wearing only gloves and a mask, and not the complete PPE. Healthcare workers treating COVID-19 are advised to wear specialized full body gowns, including N95 masks.

Similar but more widespread contagion in south Mumbai’s Wockhardt Hospital, after a cardiac patient developed COVID-19 symptoms, has led to the hospital being turned into a containment zone. More than 50 staffers had tested positive for the disease by April 7, 2020, Shah said, now in isolation at home.

“One person who came in for heart issues led to this situation and it highlights how all of us and our families are at risk,” said Ranjana Athavale of the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) Nursing and Para Medical Staff Union. The nurses worry for their own safety as well as that of their family members, she said.

Hospitals have advised their staff to avoid returning home if they can and some states, such as Maharashtra, have provided alternative accommodation for healthcare workers. But that is not an option for everyone. Many nurses have little children and have to return home to take care of them, said Athavale.

Athavale said N95 masks or, at the very least, surgical masks and HIV kits (that include a basic full-body apron), should be provided to all healthcare workers, irrespective of whether they work in the COVID-19 ward or not.

Due to a shortage of PPE such as N95 face masks, the government has recommended that healthcare workers be administered HCQ, the anti-malarial drug, as a preventive against the disease, IndiaSpend reported on March 29, 2020. However, the efficacy of this drug for preventing COVID-19 infections is unproven, as we mentioned earlier.

“When we are wearing a PPE we [women] can’t go to the washroom without taking it off completely, eat or have any fluids for hours,” said Athavale. “Since there are limited PPE and we don’t have the luxury to use multiple ones in the same shift, we remain in discomfort.” PPE reuse is not recommended, but there have been reports that staff at some government facilities have been asked to reuse PPE.

The regular drill for Shah, to keep the infection away from his family, was to change into scrubs once he reached the hospital, don PPE to do his rounds, and when he was done for the day, properly doff the PPE, wash the scrubs, take a shower and change back into his day clothes. Once home, Shah said, he would shower again, wash his clothes separately and make sure to use utensils stored separately.

The way forward

As India allows more private labs to test COVID-19 samples, biosafety concerns will increase, doctors said. “The viruses which are transmitted by droplets such as SARS-CoV2 [novel coronavirus] need special care,” said Singh of BHU, adding that it is critical to ensure no spillage during the testing of a sample. “These are very important things required to be explained by experts to the technicians or other staff engaged in such work.”

Going forward, “patients who can isolate themselves at home should be allowed to”, said K Sujatha Rao, former principal health secretary of India, so as not to overburden the healthcare system.

(Shetty is a reporting fellow and Khaitan is writer/editor with IndiaSpend. With inputs from Anoo Bhuyan, a special correspondent with IndiaSpend.)

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@indiaspend.org. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.