Inequality is Bad for Everyone’s Health But Affects The Poor the Most: Study

In states with a higher concentration of wealth among the rich, more people are likely to fall sick

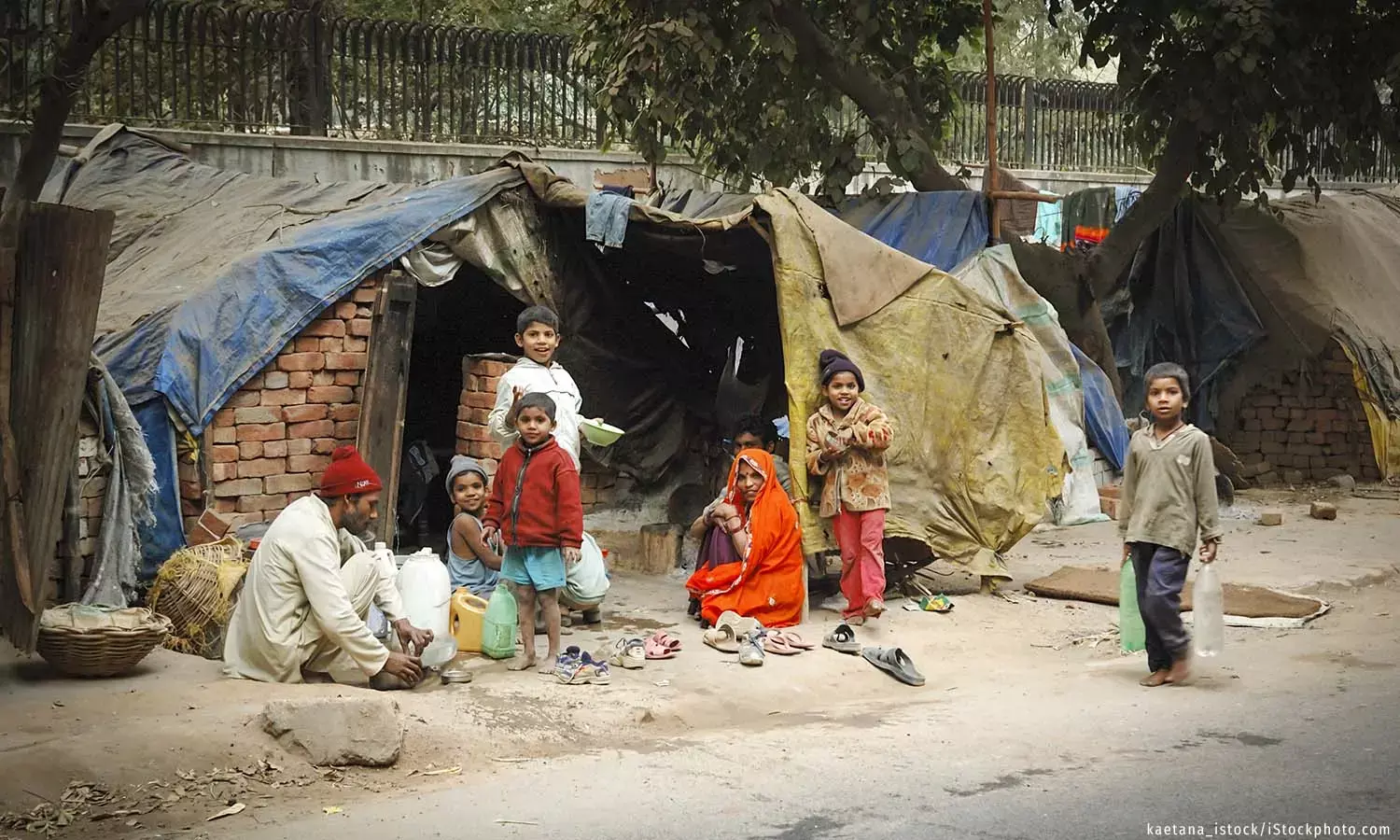

Noida: Income inequality in a state causes more people, especially the poor, to fall sick in the short run, finds a June 2023 study based on data from India.

Household income has a direct and quantifiable effect on health--thus, people belonging to high- and middle-income households are less likely to fall sick (have a member who experienced fever, cough or diarrhoea) in the 30 days preceding the India Human Development Survey (IHDS)--on which the study is based--than those from low-income households. The study also found that women of low-income households are more likely to fall sick than men.

Income inequality is one of the ways in which marginalisation affects the health of communities--for instance, structural racism is known to affect the health of the African American community in the USA. Similarly, lower socio-economic status and smaller landholding among the Scheduled Castes are associated with poorer health in India and Nepal.

“Income poverty and inequality affect individual health in terms of short-term morbidity in the Indian context as reflected by nationally representative data,” explained Sohini Paul, the author of the study and Senior Programme Manager at the Population Council Consulting Pvt Ltd of India.

Paul uses psychosocial theory to explain the effect of inequality--which is a result of social, political and economic processes--on the health of a person.

Polarised income distribution, smoking result in poorer health

The author measured inequality via the ratio of the share of wealth accruing to the richest and poorest households, and the coefficient of variation (which measures the difference of a statistic from its average value) of household income at the state level. In both instances, the higher the income inequality, the more people are likely to fall sick in a state.

The study is based on data collected from all over India, as we said, under the IHDS conducted by the National Council of Applied Economic Research, New Delhi in 2004-05 and 2011-12.

More recent data, such as those from the National Sample Survey or the fifth National Family Health Survey may show that access to healthcare has improved since then, especially after the rollout of schemes like the Pradhan Mantri Jan Aarogya Yojana (PM-JAY) and the Pradhan Mantri Ayushman Bharat Health Infrastructure Mission (PM-ABHIM), explained Anup Karan, a health economist and professor at the Public Health Foundation of India. “Regardless, the relationship between health outcomes and income inequality stands,” he added.

The topline from the study is that in states where the difference in the share of income between the wealthiest 10% of households and the poorest 10% of households is high, the proportion of people who fall sick is correspondingly higher. Individuals from poorer households from places with high income inequality were more likely to report short-term morbidity (from cough, fever and diarrhoea) compared to those from wealthier households in the same areas.

Women are more likely to fall ill compared to men, irrespective of household wealth, found the study. Similarly, people belonging to scheduled castes were 5% more likely to fall ill compared to the other backward castes.

Education status also affects health--in 27% of the households surveyed, those with higher education fell sick less often than those with significantly lower education levels. People in the states of Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Chhattisgarh, Bihar and West Bengal had the highest proportion of people who reported short-term morbidity in the month before the survey.

People living in urban areas were less prone to fall sick compared to those in the rural areas, regardless of income.

The study excluded the effect of access to insurance because very few people in the sample had access to health insurance.

“People in equal societies have more public goods, social support, social capital, etc.,” explained the study. “Unless you have money, you cannot access healthcare, therefore people with lower ability to pay are at a disadvantage if they have to buy their healthcare from the private sector,” explained Karan.

Paul’s study also found that smokers reported more short-term morbidities in the recent past, with the probability of short-term morbidity being 23% higher for smokers compared to non-smokers. However, alcohol consumption did not influence health outcomes, the study found.

Smoking is more common among the poor in India as well as abroad (see here and here).

Health is affected by “relative deprivation”, or the condition of a household compared to others in a community. Theoretically, as people work harder to overcome their challenges, they have less time and energy to focus on health, which economists call “investing in human capital”.

In the short run, while their efforts do not seem to improve their living conditions, they cope with the stress of their life by developing unhealthy behaviours. Weathering, a term used to describe the peculiar ageing processes of members of the African American community, is an example of the effect of socioeconomic and political factors on health.

Karan uses the example of “healthy Covid behaviour” to explain the role of environmental variables, but emphasises that the financial condition affects the health of a household the most. “We saw that the poor were unable to practise social distancing, etc. during Covid,” he told IndiaSpend. “It affected everybody, but ultimately there were those who could buy their healthcare and those who could not.”

Improve access to healthcare, sanitation in the short run: experts

Theoretically, a small transfer of wealth from the richest to the poor will result in better health for the poor without affecting the average health of the society, says the paper. Cash transfers were found to reduce the likelihood of reporting illnesses in a review of 34 studies from Africa, the Americas and Southeast Asia.

Policies like a wealth tax on individuals with high income, or a tax on corporate income, can help. However, it is easier to equalise access to nutrition, sanitation, etc., according to Karan.

“Righting the income distribution is a worthy goal but it is easier to improve the health status of a society by ensuring that everyone has access to clean water, sanitation facilities, food, etc. and providing adequate risk protection for vulnerable families,” he said.

The aim is to narrow the income distribution gap; otherwise relative deprivation and the ills associated with it will still be around, said Paul. “Instead of just increasing the national income, the focus should be on decreasing the income inequality,” she said. Schemes like the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme, the rural employment programme, can help reduce poverty in the areas where the health outcomes are the poorest, she added.

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@indiaspend.org. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.