Rajasthan Is Getting More Rain. That’s Not Good News

Tilonia, Rajasthan: Shambhuji Sain took to farming as a teenager, learning from his grandfather and father during an era when the heat, winds and rain intermingled in a steady pattern, and the annual southwest monsoon swept up the subcontinent almost like clockwork.

Sain is now 49, his luxuriant moustache and beard prematurely gray, as he explained how the rain in this part of Rajasthan began to change after the turn of the century. “I haven’t seen a good shower of rain during the monsoon season over the past decade,” he said, as he sat cross-legged on a sagging hemp charpoi inside his modest two-room brick home in Chhota Narena village, a 90-minute drive to the west of state capital Jaipur.

This year, Sain could grow only two bags of jowar instead of the regular yield of 20 bags on his acre of land, a little larger than an average football field. Sain could not even recover the costs of seeds and pesticides, a story repeated by other farmers in Chhota Narena.

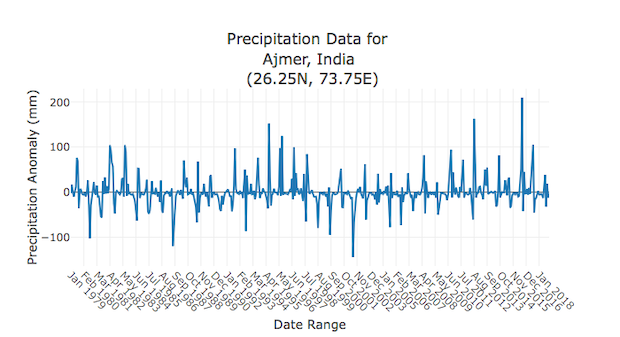

Yet, there is a scientific conundrum unfolding: Chhota Narena is in Ajmer’s Siloria block, an area that has been receiving more rainfall over the decade to 2018, compared to 29 years before that, according to satellite data, as you can see below in the spikes on the right end of the graph.

Rainfall deviations in Ajmer district from the average over 29 years to 2018.

Source: NOAH, an application that shows changes in rainfall and surface water using satellite data.

But a closer look at the data backs Sain’s experience and follows the general global and Indian observations of more erratic rainfall linked to climate change--spells of torrential rain interspersed by unusual dry periods.

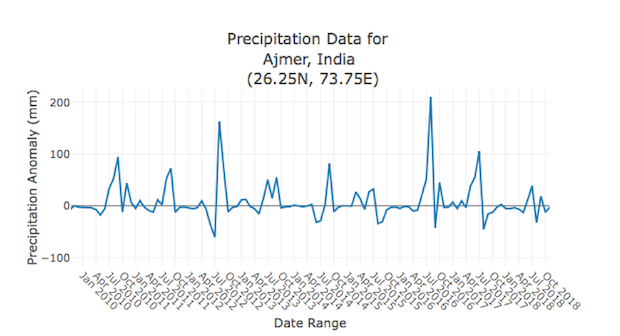

As the graph below indicates, the rainfall in Ajmer has become increasingly erratic over the decade to 2018.

The straight line is the average rainfall for the region. Peaks highlight heavier-than-normal rainfall and troughs, deficits.

Source: NOAH, an application that shows changes in rainfall and surface water using satellite data.

In 2011, for instance, the rainfall in July over Ajmer district was 80 mm above the average. The following year, there was a 50 mm deficit the same month. In 2013, July rainfall was 50 mm above the average.

This is a pattern, said experts, evident nationwide: A seemingly normal monsoon with new peaks and lows in rainfall.

“If you see the all-India monsoon rainfall there may not be any trend,” said Pradeep Mujumdar, a professor of civil engineering at the Indian Institute of Sciences (IISc), Bangalore. “But there is a distribution of rainfall within a season and that may have been affected by climate change. In many situations that we have studied, it (rainfall) does appear to be affected, in terms of most of it occurring in certain part of the season in a concentrated manner.”

This is the seventh and last story in our series on India’s climate-change hotspots (you can read the first story here, the second here, the third here, the fourth here, the fifth here and the sixth here). The series combines ground reporting with the latest scientific research and explores how people are adapting to the changing climate.

As in Ajmer, so in Rajasthan and India.

Climate change in several states is an added stressor on agriculture, already stressed by various resource and policy related issues, as IndiaSpend reported in January 2019. Erratic rainfall increases distress migration, which we will discuss later in the story, and particularly impacts the quality of life of women and public health.

Consequences of erratic rainfall

Failing farms are a leading political issue in the general elections of 2019, but climate change, an exacerbating factor, is not.

Agriculture generates no more than 18% of gross domestic product but sustains 600 million people--half of India’s population. Nearly 69%, or 833 million Indians--most of them poor--live in rural areas, where half of all farms depend on rainfall.

Crops cannot survive unpredictable rainfall, said Sain, the farmer. Such erratic rainfall is a fallout of climate change, an issue discussed in an October 2018 report by the Intergovernmental Panel for Climate Change (IPCC), the world body for assessing science related to climate change.

Extreme rainfall shocks increase the risk of floods, which Rajasthan witnessed across many cities in 2017. India could see a six-fold increase in population exposed to such floods by 2040--to 25 million people from 3.7 million between 1971 and 2004--if no efforts are made at mitigation, IndiaSpend reported on February 10, 2018.

In discussing the growing evidence of heavier rain in Rajasthan, experts pointed out that the term “heavy rainfall” is relative. Mumbai receives as much as 800 mm of rainfall in the monsoon months of June to September, which is 200 mm per month. Cherrapunji in Meghalaya receives as much as 11,000 mm annually, on average, according to the India Meteorological Department (IMD) data, which is around 900 mm per month.

In Ajmer, 200 mm in July, 100 mm more than the average, counts as “heavy”.

Ajmer’s heavier but more erratic rainfall has had unforeseen consequences.

Once India’s largest inland salt water lake, the Sambhar lake in central Rajasthan has all but dried up. It is just one of the lakes to dry in this area, according to satellite data for three decades till 2015.

A drying land

At first glance, the vast stretch of land an hour’s drive west of Jaipur looked like a patch of desert overlooked by rolling hills (see photo above). It was a hot afternoon in the last week of March. Summer had just set in, and temperatures were already in the mid 30s (deg C).

A closer look at the land reveals cracks, not the fine, shifting sands of a desert. Three decades ago, this land was at the bottom of India’s largest inland salt water lake, the 190 sq km Sambhar lake.

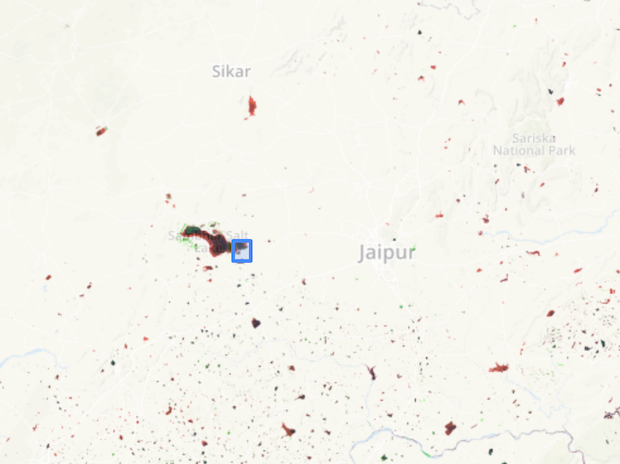

Today, it has all but disappeared, as have several lakes and ponds in and around Jaipur, according to satellite data of the area over three decades to 2015, as the image below reveals.

Satellite data on the changes in surface water in and around Jaipur show that several water bodies have either dried out or shrunk in size. In the centre, in blue box, is the 190 sq km of the Sambhar lake. The red indicates water bodies that have reduced in size, while green indicates an increase in the amount of water. Black indicates that the water bodies are the same size.

Source: NOAH, an application that shows changes in rainfall and surface water using satellite data.

The amount of mean rainfall in Rajasthan increased before 2008 as well but “not in a significant” way, according to a 2006 study on trends in rainfall patterns over India by the IMD, which looked at data for over a century, from 1901 to 2003.

If the rain has not declined over more than a century and significantly increased over the last decade, then why are Rajasthan’s lakes drying?

This pond (above) in Harmara village in Rajasthan’s Ajmer district had water till May every year. For two years to 2019, it has dried out by January, according to locals. This picture was shot in the last week of March 2019.

The curious case of Rajasthan’s drying lakes

Think of a potted plant, said Sandeep Sahany, assistant professor at the Centre for Atmospheric Sciences, Indian Institute of Technology - Delhi (IIT). Water the soil slowly, and the water percolates to the roots. Flood the pot, and most of the water will run off.

That’s how short, heavy spells of rain work: There are floods, the water runs off and does not recharge the groundwater that farms use, particularly in Rajasthan, where more than 75% of crops depend on the rain.

The drying lakes are a more complex story.

“The lakes are recharged in two ways,” said Sahany “One, the rainfall, which it (lake) will catch. Second, the groundwater. When this (ground water table) goes down, the lakes lose their second source of recharge.”

There are overarching global factors at play as well.

The earth’s temperature is rising by 0.2 degree C every decade, according to a October 6, 2018, report by the IPCC. By 2030 and no later than mid-century, the warming will reach 1.5 degree C when compared to pre-industrial-age temperatures.

“Increase in temperature is a certainty,” said Sahany. “With an increase in temperature, there is a higher rate of evaporation,” said Sahany. For the lakes, this is a double whammy. They are not just losing one of their major sources of water but the water they contain is also being lost at a higher rate.

This is not to say climate change is the only reason for the water shortage. Other reasons include an increase in population, fewer trees, more construction and pollution of water.

“They (other activities) have already increased the stress on the water system enormously but climate change will bring in an additional stress,” said Mujumdar of IISc Bangalore. “This is additional stress, because it adds to the existing stress, becomes really significant.”

At the forefront of the stress caused by the water crisis are women.

Gayatri Vishnawat, 23, from Chhota Narena in central Rajasthan’s Ajmer district says filling water takes up to three hours every morning and the lives of women in most villages revolves around this task.

Aching bodies, parched throats

Gayatri Vishnawat, 23, spends two hours in the morning around a communal borewell 500 m from her home in Chhota Narena.

It takes her between five and seven trips to fill enough drinking water for her family of four before she travels by hitchhiking 70 km to a college where she is studying towards a Bachelor of Education degree.

“My body hurts all the time,” she said, echoing the sentiment of women in other water stressed regions of the country.

The rest of the water comes from tankers. A tanker of water costs Rs 300, and a family of five needs three tankers every two months.

Not everyone is a loser in the situation. Some families with enough water in their borewells have turned tanker suppliers, an informal trade they hesitate to discuss.

The quality of this groundwater is suspect. “At times it looks yellow in colour. Sometimes we end up vomiting after drinking the water,” said Vishnawat.

Fluorosis, caused by drinking water high in fluoride, is common in many villages in the region, as it is in parts of the country where people depend on groundwater. The condition causes dental and other skeletal deformities.

“We tested 2,176 water sources in 210 villages in Ajmer and Jaipur district and found 1,229 sources were contaminated with fluoride,” said Dadi Jaswanth, who is a programme coordinator in the water department with the NGO Barefoot College.

With a water crisis this acute, finding water to irrigate land is next to impossible.

Many farmers turn seasonal migrants, abandoning agriculture and entering unorganised professions, such as stone mining and its allied industries. The highway leading westwards from Jaipur to Ajmer is lined with factories, such as the one above. Stone mining and cutting needs a continuous supply of water, pumped out from aquifers.

Distress migration

“The government can give us free electricity but what do we do when the ground water runs dry and there is no water for the pump to pull up?” asked Sain, the farmer.

Between 2002 and 2008, data from the US’s The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) satellites suggested that groundwater across northwest India was reducing faster than it was being naturally replenished, according to findings published in the scientific journal Nature in 2009.

The groundwater in many district of southern Rajasthan has reduced, and the number of rainy days has gone down from 101 in 1973 to 46 days in 2010, observed a 2013 study that explored the impact of climate change in the state.

Sain’s son, like others in the village, has abandoned agriculture for work in a nearby stone quarry, a dangerous job, killing many by silicosis from inhaled dust, tuberculosis cases and accidents. “Hundreds of our youths die doing this work every year,” said Sain.

There are few options though.

In Rajasthan, over 8% of the population, or an estimated 5.79 million people, from rural areas turn seasonal migrants, according to a 2014 report by the Aajeevika Bureau, a nonprofit that works with migrants.

While western Rajasthan, which receives the lowest rainfall (102.57 mm) statewide, sends the largest number of migrants, the fertile alluvial soil rich and forested southern Rajasthan too now send migrants, as forests are cut down for mining and other extractive activities, according to a 2014 Aajeevika report.

“In the interviews, poor households are talking about the dramatically reduced and erratic rainfall, groundwater depletion and soil depletion as the most common reasons for migration,” said Priyanka Jain, an Aajeevika researcher.

The situation is not unique to Rajasthan.

Climatic drivers shape migration decision and are behind many people moving from agriculture to the informal sector, according to a 2017 study in Karnataka’s Gulbarga and Kolar region by the Indian Institute for Human Settlements (IIHS) in Bengaluru.

Rajasthan’s changing climate also has wider implications for 600 million Indians living across the Indo-Gangetic plain. This population is already feeling the impact of air pollution, as we reported earlier in this series. More dust from Rajasthan’s deserts could worsen that pollution.

The National Aerosol Facility being set-up at Indian Institute of Technology, Kanpur, Uttar Pradesh, will offer more insights on the role that dust from Rajasthan’s desert plays in rainfall and air pollution in the Indo-Gangetic plain.

Preparing for the future

Spread over 1,000 acres, or the size of nearly the same number of football fields, is the lush campus of the Indian Institute of Technology, (IIT) Kanpur, in the heart of the Indo-Gangetic plain.

Here, a new lab is under construction. When ready, it will study aerosol particles, such as dust, ash and sea salt suspended in air, some of them invisible to the naked eye.

The equipment at the National Aerosol Facility will offer insights into the nature of these particles, smaller than the head of a needle, their role in air pollution over the Indo-Gangetic plain and the role of dust from Rajasthan, among other research.

“We will study the sources of aerosols and how to mitigate them,” said Sachchida Nand Tripathi, professor and head, department of civil engineering, IIT-Kanpur. “It could give us a deeper understanding of the air pollution over cities like Delhi.”

IIT Delhi’s Sahany explained how rainfall changes in Rajasthan and dust and air pollution over cities like Delhi were connected.

“Rain essentially cleans the air,” said Sahany. “But if it rains for lesser number of days then the dust will remain in the air longer.” Winds carry this dust to other cities in the Indo-Gangetic plain, adding to the pollution. Irrigation mitigates the effect of dust and pollution by moistening the soil and binding it, he said. Dust also plays a role in the formation of clouds, affecting rainfall, as we explained in an earlier story. There is limited research on the interaction between dust and rainfall, apart from some studies in India and China, said experts, a gap that Tripathi’s IIT Kanpur laboratory hopes to fill in the coming years.

For Sain, the farmer in Chhota Narena, the concerns are more immediate. The government doesn’t bother about the poor, he said, and making their voice heard requires a trip to where the authorities are.

“One trip alone won’t get results,” said Sain. “The bus ticket to Ajmer and back can cost over Rs 100. Who has that kind of money?”

Correction: The spelling of Shambhuji Sen has been changed to Sain to make it more phonetically accurate.

(Shetty is a Columbia Journalism School-IndiaSpend reporting fellow covering climate change.)

This is the seventh and last of a series on India’s climate change hotspots. You can read the first part here, the second here, the third here, the fourth here,the fifth here and the sixth here.

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@indiaspend.org. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.