The Mystery Of India’s Child Malnourishment Numbers

Two weeks ago, IndiaSpend put out a report on child malnutrition in India, using Government of India, Ministry of Health data to show how child malnutrition in the country is worse than sub-Saharan Africa. We also pointed out that this is a problem across states, though the degrees vary.

Two weeks ago, IndiaSpend put out a report on child malnutrition in India, using Government of India, Ministry of Health data to show how child malnutrition in the country is worse than sub-Saharan Africa. We also pointed out that this is a problem across states, though the degrees vary.

The report invited several comments, one of which referred to an interview with well-known Columbia University professor, Arvind Panagariya, where he sharply differs with the generally held view on India’s child malnutrition numbers. The headline sums up his main thesis: “Once we do our malnutrition numbers correctly, we will find that India has no more to be ashamed of its malnutrition level”.

IndiaSpend’s Dr. Julie Hudman uses this claim as a trigger to revisit the data and discuss what most experts (India and worldwide) say about Indian children’s nutrition levels.

Let’s begin with the base data, which shows that 43% of India’s children under 5 are underweight (or, malnourished) – far above India’s Millennium Development Goals 2015 target of 26% by 2015.

As we reported, according to UNICEF and the World Health Organizations’ Global Health Database, India has more malnourished children than sub-Saharan Africa and nearly one in every 5 malnourished children in the world is from India. Malnutrition is one of the leading causes (about 50%) of all childhood deaths. And malnourishment at an early age can lead to long-term consequences as it affects motor, sensory, cognitive, social and emotional development.

Now, let’s look at Professor Panagariya’s two arguments which advocate that India’s malnutrition numbers are flawed. The first is that the World Health Organization’s (WHO) standard reference population is flawed because it does not account for the fact that, genetically, Indian children are smaller and shorter then Western children. On the face of it, this seems like a reasonable argument.

Indian children here ARE smaller and shorter than say children in many western countries. Well, that is the point – they are smaller, but according to most experts, it is not for genetic reasons rather because of social and development factors. This “small but healthy” hypothesis was first debunked in 1980 – and the academic community to date generally agrees that there are no genetic reasons why children in certain countries are just always going to be smaller than others.

To combat the argument that the reference population was not a representative sample (only had US children), in 2006 the WHO started using a new sample of healthy children that was drawn from India, Brazil, Ghana, Norway, Oman and the US – and this is the population that Indian children are now compared to. Panagariya dismisses this as inadequate and still not properly accounting for “smaller and shorter” healthy Indian children.

Second, Panagariya argues that the data does not pass the “smell test” (his words). How, he wonders, can India’s malnutrition data be so much worse than sub-Saharan Africa when other measures (such as under 5 mortality and life expectancy) are better in India? This argument too seems pretty sensible to most readers. However, if you think about it, there are a multitude of reasons babies born who are malnourished sadly die before their 5th birthday or die before they reach 60 or 70 years old.

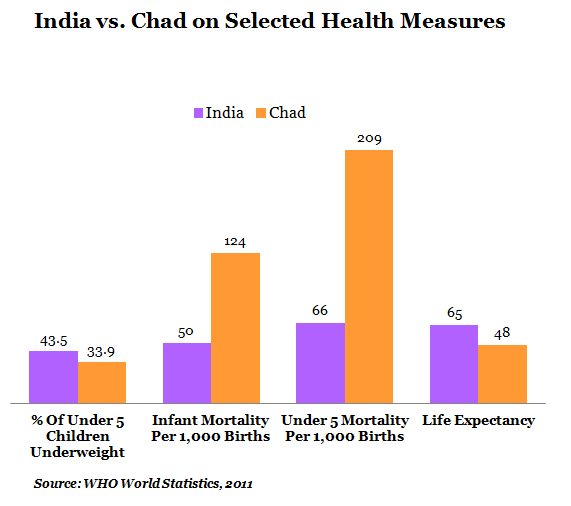

To illustrate his point, Panagariya compares data from the sub-Saharan African country of Chad to India – see the graph below. Chad’s child malnutrition stands at 33.9%, while India is at 43.5%, but on many other health measures (e.g., infant mortality, under five mortality, life expectancy) Chad does worse than India.

Referring to these apparent inconsistencies, Panagriya concludes, “it can’t get more absurd than this.” Let us explain how these numbers can make sense. Are children’s malnutrition data and under five mortality correlated? Or more importantly, does malnutrition cause death?

While malnutrition has been reported to account for over 50% of deaths for children under five, not all children who are malnourished die. Furthermore, kids and adults die from many other things too – accidents, HIV, malaria, political unrest/war, cancer, heart disease, TB, suicide and murder.

So what about Chad – a country that has half the per capita income of India but about 10% less children malnourished? Writers for a Kolkata-based publication, Sanhati, found that compared to India, Chad had ten times the rate of HIV infection, has less than 10 percent of the population with access to “improved sanitation facilities” (vs. 31% in India), significantly lower per capita expenditure on health care services and facilities (94 vs. 132 US Dollars), and a huge influx of political refugees from Darfur and Center African Republic. In Chad, it seems, children and adults are dying from many things other than malnutrition.

Figure 1

What about other, comparable South Asian countries? Aren’t they more similar in physical and genetic features as well as economic development (save China) to India than say the US or Sub-Sahara Africa?

Professor Panagariya seems to think so --in the interview he referenced a study that concluded that South Asian descendants living in South Africa, Fiji, and US had a predisposition for low adult BMI (Body Mass Index) – arguing that South Asians are just smaller, and since India is a South Asian country, that is why India’s data on children’s nutrition is bad.

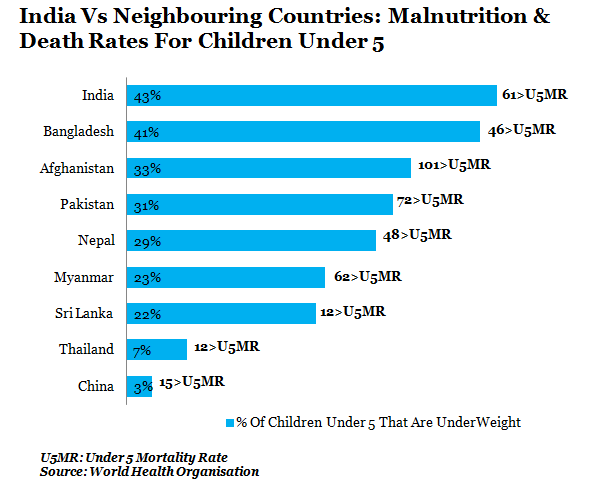

Let’s compare the data of our South Asian neighbors to India on children’s malnutrition and deaths before 5 years old.

Figure 2

Every single South East Asian country listed here has a smaller percentage of children than India who are classified as underweight. Bangladesh is the closest to India with 41% of its children underweight while some other close neighbors – Sri Lanka (22%), and Myanmar (23%)-- have nearly half the number of malnourished children as India (43%). Thailand and China, meanwhile, both have percentages less than 10% of children malnourished.

For children under five, India has 61 deaths per 1,000 live births. Of the countries that surround India, only the war torn, politically volatile nations of Pakistan (72), Afghanistan (101), and Myanmar (62) have more children die before they reach their 5th birthday. Sri Lanka and Thailand are doing the best of the group of SE Asian countries, with 12 deaths per 1,000 births – a rate much closer to world leaders Singapore, Sweden and Japan (among others) that have 3 deaths.

If the widely accepted international standard is skewed towards more Western physically traits, how does Professor Panagariya explain that every single neighbor of India is doing better on children’s nutrition measured by weight?

These data beg the question -- why is India’s problem that much worse than most all other countries in the world? Veena S Rao, a former Secretary to the Government of India and current Advisor to the Karnataka Nutrition Mission, provides one explanation. She argues that the low status of the girl child, deeply rooted in culture and structural discrimination, severely and negatively impact food consumption. “The Indian adolescent girl,” she writes, “is the most underweight in the world.”

This is the case even during pregnancy -- the typical Indian mother gains 5KGs during pregnancy, but African mothers gain 10KGs. This directly leads to low-birth weight babies --30% of babies born in India are low-birth weight in India, which is a much higher percentage than all of the African countries. And this high level of babies born with a low weight directly leads to the number of underweight children in India.

Another possible explanation is the issue of scale – India has so many people and so many challenges that it is just harder to tackle malnutrition then in Sri Lanka or Nepal. Or maybe it stems from ineffective program implementation or prioritizing by the Indian government.

There is evidence that India is improving, albeit slowly, on the issue – no “developed” nation has a serious issue with malnutrition. India has decreased its malnutrition by 10 percentage points since 1991 -- from almost 53% to 43% in 2005-06. It might be worth looking at newer data from the HUNGaMA (Hunger and Malnutrition) Survey, which was conducted across 112 of the poorest, rural districts of India and found promising improvements in child nutrition.

Also, a recent survey data on Maharashtra’s nutrition status by UNICEF has very encouraging early findings on stunting (short for their age) which decreased in children under-two from 39% in 2006 to 23% in 2012 -- and severe stunting decreasing from 15% in 2006 to 8% in 2012. These positive trends are seen both in rural and urban areas.

We cannot say that India's malnutrition numbers are right but nor does Professor Panagariya. But his reasoning for saying they are exaggerated would appear flawed – and it could be argued that his conclusions are counterproductive to the efforts by the Indian government and others to do something about it.

There are several serious questions though, around India’s high malnutrition among children – the Food Security Bill’s ability to address the problem of malnutrition; the challenge for state governments to provide children Vitamin A; or new research showing that inexpensive antibiotics along with nutritious food can save tens of thousands of lives – many of those in India. These debates could actually help continue the slow, but positive, trend in India’s battle against malnutrition.