The Rs 110,000 Crore ‘Enhancement’ Figure In India’s Food Security Bill

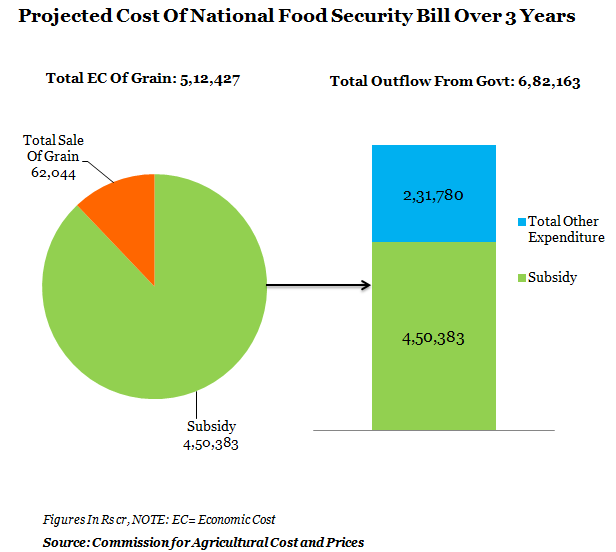

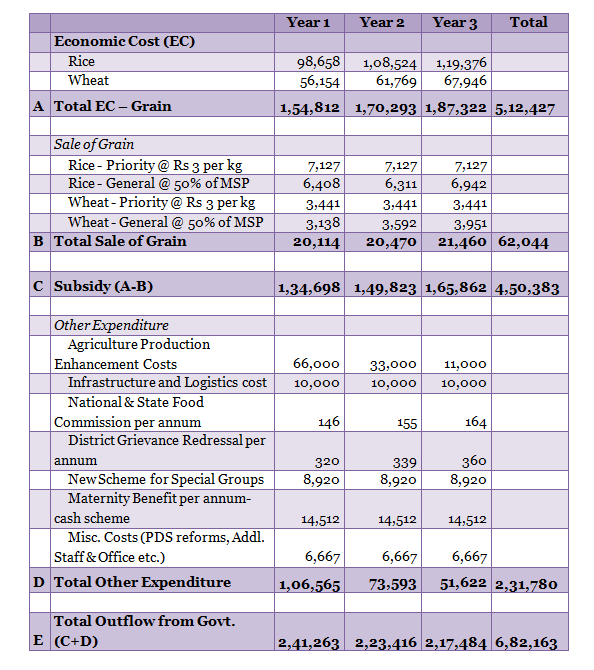

| Highlights * The National Food Security Bill is estimated to cost Rs 6,82,163 crore over three years

* Agriculture ‘production enhancement cost’ estimated at Rs 66,000 crore in first year, Rs 11,000 crore in third year

* Infrastructure and logistics expenses constant over 3 years |

India’s National Food Security Bill (NFSB), which plans to cover around two-thirds of the country’s population of 1.25 billion, threatens to ratchet up the subsidy burden substantially.

But it’s not just the subsidy figure that will strain the exchequer. A report by the Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices (CACP) says the Government’s attempt to ensure food security would mean spending some Rs 66,000 crore for boosting production in the first year alone, a sum which would decline to Rs11,000 crore by the third year.

Why such a huge cost for agriculture production enhancement, which will go towards investing in “productivity-enhancing technologies like irrigation, power, fertilisers, seeds and post-harvest technologies.”?

Here is a backdrop and the possible reasons;

- The average growth rate of food grain output declined from 2.2 % in the 1990s to 1.8% in the 2000s

- The average growth in yield (kilogramme/hectare) also declined from 2.4% in 1990s to 1.3% in the 2000s; and

-Agriculture growth at a trend rate of 2.9% during 1991-92 to 2011-12 is much lower than the targeted 4% in the Five-Year Plans

Indian agriculture is highly dependent on monsoon, and if production or buffer stock comes down, it takes almost two years to fill the gap. Around 50% of area under cultivation is at the mercy of monsoons. Perfect volatility was seen in the year 2002-03 when production of wheat and rice fell by 28.5 million tonne from 2001-02, and it took three years for the production level to increase to the 2001-02 level.

To minimise the risks of volatility and to maintain a sustained flow of production, CACP estimates that there will be a big cost in the first year, which could eventually scale down.

Now to the figures. Abhijit Sen, Member of Planning Commission (Agriculture), recently said that “there will be [a] subsidy increase due to the food bill but not as much as some people are exaggerating.” Media reports quote Food Minister KV Thomas saying that it is likely to cost an additionalRs20,000 crore to the taxpayers.

IndiaSpend had earlier reported how the Food Security Bill could lead to higher subsidies. Here’s another angle to the story: the expenditure for three years, as estimated by CACP would amount to Rs 6,82,163 crore.

Source: National Food Security Bill: Challenges and Options

3 assumptions for cost calculation

1. CACP assumes that approximately 70 million tonne will be the annual requirement of food grain for implementing NFSB. Priority recipients identified by the State Governments would require40.96 million tonne, general recipients would require11.63 tonne, and buffer stock/other welfare schemes would require around 20 million tonne.

2. The wheat : rice ratio of stock has been assumed at 42:58% based on the total off take from 2009-10 till 2011-12. For example, procurement and allocation for food grain range from 30 million tonne in 2004-05 to 42 million tonne in 2009-10 under TPDS, while, in the same period, allocation was 70 million tonne in 2004-05 and 48 million tonne in 2009-10.

3. Year 1’s economic cost is calculated at the 2012-13 level of Rs19,100 per tonne for wheat and Rs 24,300 per tonne for rice. The commission has further assumed that future years’ economic cost will increase by 10% annually.

An analysis of the table shows us that the economic cost of food grain will increase by 21% from Rs154,812 crore to Rs187,323 crore. Total sale of grain would increase from Rs 20,114 crore to Rs 21,460 crore, up 7%. And total subsidy, which is the difference between total economic cost and total sale of grain, would increase by 23% from Rs 134,698 to Rs 165, 862 crore.

Furthermore, total other expenditure, as compiled by ‘internal calculations of different ministries and departments,’ drops from Rs106,565 crore to Rs 51,622 crore, a 52% decline.

Finally, total outflow from Government is estimated to come down from Rs 241,263 crore to Rs 217,485 crore. Therefore, we can see that the total cost for the NFSB declines by 9.8% over the years, mainly due to the decline in the “agricultural production enhancement cost.”

Now for a closer look at the other variables.

The CACP report also estimates that the cost of infrastructure and logistics would be Rs10, 000 crore. The public distribution system needs expansion, considering that more than 30% of grains supplied through the system are lost due to storage constraints every year. The problem is expected to worsen due to the expected expansion of PDS to encompass two-thirds of the population.

Another example could be Food Corporation of India’s insufficient storage capacity. FCI has around 37.5 million tonne of storage capacity while the central pool stock was around 80.5 million tonne in 2012.

FCI also needs to revamp its procurement process in surplus/ self-sufficient states like UP, Bihar, West Bengal, Assam and Orissa. Presently, FCI’s procurement is mostly concentrated in the Northern and Southern states. Therefore, a static level of cost for infrastructure and logistics seems surprising.

Other Challenges

While we can see that the total cost will come down in the third year, it still could be as high as Rs 682,163 crore, which may increase the already high fiscal deficit. High fiscal deficit, coupled with probable high demand for food grain may lead to more inflationary pressures.

Agriculture in India is seeing high productivity in fruits, vegetables and livestock now but the CACP paper highlights that farmers will be more interested in producing rice and wheat, thereby disturbing the equilibrium, leading to more imports (translating to more dollar outflow) of other items.

Labour costs in agriculture will also increase due to the MGNREGA impact (people shying away from agriculture), and it is evident for the last three years. In some states, agriculture labour costs have increased by 100%.

The question still stands: Will NFSB guarantee food security? The FAO’s 2001 ‘State of Food Insecurity in the World’ report explained that food security exists “when all people, at all times, have physical, social and economic access to sufficient, safe nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life.” In short, food security refers to four criteria: availability, access, proper utilisation, and stability.

And the Indian Government is trying to guarantee just that. NFSB would guarantee either free or heavily subsidised rice, wheat and coarse grains for all under-14 children, pregnant and lactating mothers in eligible households, destitute and malnourished people. The food articles would cost these groups at mostRs3 per kg.

In a sense, NFSB would mark the shift from food being regarded as a product of welfare to food being regarded as a right guaranteed by the State.

The Way Ahead

The CACP report states that conditional cash transfers would probably be the best method to implement such welfare measures. The model has already been followed by BolsaFamilia, the largest cash transfer scheme run by Brazil that has lifted millions out of poverty. The Indian Government has started implementing cash transfers in select districts using Aadhaar cards (incidentally, only around 30% Indians have Aadhaar numbers!).