Annual Crop-Burning Health Bill = 3 Times India’s Health Budget

Mumbai: India’s five-year air-pollution-related health bill from burning crop stubble can pay for about 700 premier All India Institutes of Medical Sciences or India’s 2019 central government health budget nearly 21 times over, according to an IndiaSpend analysis of data from a new study.

Burning of crop residue or stubble remains a key contributor to air pollution over northern India, despite a ban by the National Green Tribunal (NGT) in November 2015, and will cost the country over Rs 2 lakh crore annually, or three times India’s central health budget, or Rs 13 lakh crore over five years--equal to 1.7% of India’s gross domestic product (GDP) or enough, as we said, to build 700 AIIMS hospitals, according to a 2019 study by the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), a research advocacy based in Washington D.C., USA.

Crop-residue burning causes a collective loss of 14.9 million years of healthy life among the 75 million residents of Delhi, Haryana and Punjab--72.5 days or a fifth of a year per person in the three states--whose risk for acute respiratory infection (ARI) rises threefold due to exposure to pollution, the study says.

“We found that 14% of ARI cases could be averted if crop burning were eliminated,” Samuel Scott, IFPRI research fellow and co-author of the report, told IndiaSpend.

Crop residue burning in the north-western states of Punjab and Haryana is a key reason why levels of particulate matter up to 2.5 micron in size (PM 2.5) in the air spike by 20 times in neighbouring Delhi during harvest season, and is a major risk factor for ARI in all three states, especially among children younger than five.

In winter, particularly, 64% of Delhi’s PM 2.5 pollution comes from outside the national capital, as IndiaSpend reported on September 3, 2019.

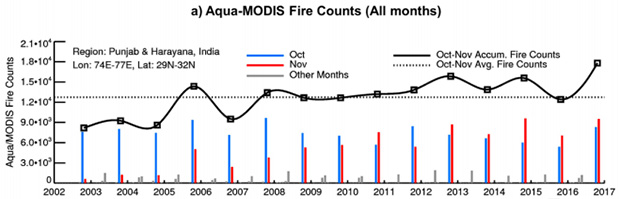

Agricultural fires in the states of Punjab and Haryana during October and November for pollution in Delhi, based on 15-year satellite records (2002-2016), showed an increasing trend in agricultural fires (up to 617 per year in 2017), according to a study by Hiren Jathava, research scientist, NASA published by the Taiwan Association for Aerosol Research in 2018.

Source: Taiwan Association of Aerosol Research, 2018

Between 1990 and 2016, indoor air pollution declined over northern India due to efforts to reduce the burning of solid fuel for household use, but outdoor air pollution increased by 16.6%, says the IFPRI study.

Why stubble burning continues

The central ministry of agriculture and farmers welfare’s (MoAFW) national policy for the management of crop residue, announced in 2014, suggested policy measures to minimise crop residue burning. The MoAFW announced an amount of Rs 1,151.9 crore for 2018-20--0.5% of the total budget of Rs 2,22,362 crore of Punjab and Haryana in 2019-20--to subsidise the use of additional farm equipment to remove crop residue, such as Straw Management Systems, in lieu of crop burning.

The NGT ban followed the next year. The tribunal has repeatedly issued orders directing the Punjab and Haryana state governments ‘to periodically review steps taken to stop crop burning incidents’, yet crop stubble burning incidents continue.

In 2018-19, the two states together spent over Rs 400 crore--around Rs 15 lakh for every agricultural worker in the two states--to prevent stubble burning. Using satellite-based remote sensing, Punjab and Haryana detected 75,563 events of crop residue burning in Punjab, Haryana and Uttar Pradesh during 2018. Punjab identified 6,193 cases and recovered Rs 19.02 lakh as compensation from farmers who burned crop residue even after the ban, while the government of Haryana identified 3,997 cases and recovered Rs 31.82 lakh as compensation, Lok Sabha data show.

Burning stubble continues because it is the only option left for farmers, Devinder Sharma, a food and trade policy analyst based in Punjab, told IndiaSpend. “The best way to distribute the [MoAFW] subsidy would have been to give it directly to the farmers instead of subsidising the machines. The agricultural lands in Punjab and Haryana are already over-mechanised and the mechanisation scheme is a burden for farmers. Farmers are ready to manage the residue if the funds are provided but agriculture is being sacrificed to keep market reforms alive by promoting and selling machines to farmers,” Sharma said.

Not only do farmers find the cost of hiring machinery exorbitant, they say the machines are not required and operating them needs specialised training.

A Straw Management System attached with a combine harvester costs Rs 1.12 lakh, a Happy Seeder that clears fields of crop residue Rs 1.51 lakh and a paddy straw chopper Rs 2.80 lakh after availing the 80% subsidy under the MoAFW’s central agriculture ministry’s guidelines for crop residue management. The average monthly income per agricultural household in Punjab is Rs 18,059 and in Haryana is Rs 14,434, as per agricultural statistics 2017 released by the government of India.

The subsidy provided by the government is for two years, after which mechanisation costs a farmer Rs 5,000 per acre, JS Samra, former CEO of the MoAFW’s National Rainfed Area Authority, told IndiaSpend. Machines such as the Happy Seeder are usable for only 20-25 days during harvest, Samra said, and lie unused for the rest of the year. “A farm machine usually works for 400-500 hours annually. A farm machine that doesn’t work for 200-300 hours is not viable. These machines are unlike a tractor that a farmer can put to other use,” Samra said.

Small and tenant farmers in Punjab and Haryana--like their counterparts across the country--have been in distress because agriculture has become unremunerative as a source of livelihood. There have been protests in Punjab and Haryana recently, including against what farmers call poor management of the NGT order to ban stubble burning.

Producing bio-fuel from crop residue is the way ahead

The foremost step to ease the issue of stubble burning is to provide funds directly to farmers, says Devinder Sharma. “A demand to the chief minister of Punjab was made by the opposition in 2018 to release a fund of Rs 3,000 crore to be distributed to the farmers in 2018 as the farmers demand Rs 5,000-6,000 per acre. If the said amount can bring down the risk of the problem causing a loss of 2 lakh crore, then it should be provided. The process of residue management should be left to the farmers,” adds Sharma.

A secondary approach can be to bring in the use of clean energy for better management of crop residue, Samra told IndiaSpend. Crop residue can be used for mushroom cultivation and paper production. Paddy straw can also be used to generate electricity, says Samra, but this method is now redundant and uneconomical because the per-unit cost of solar and wind energy is around Rs 3 while electricity from straw costs Rs 7-8 per unit, according to Samra.

The latest and most viable method, Samra said, is to produce compressed natural gas (CNG) from residue via a biological process that does not produce any spare gas or ash and provides CNG of the same quality as that derived from fossil fuels.

The bio-CNG technology is being processed by the DBT-Institute of Chemical Technology Centre for Energy Biosciences in Mumbai, says Samra, who serves as a consultant to the project. Germany-based Verbio Biofuel and Technology is setting up a bio-CNG plant at Bhutal Kalan village of Sangrur district in Punjab at an approximate cost of Rs 75 crore.

(Ahmad is an intern at IndiaSpend).

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@indiaspend.org. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.