As Farmers Kill Themselves, Uttar Pradesh Hides Deaths

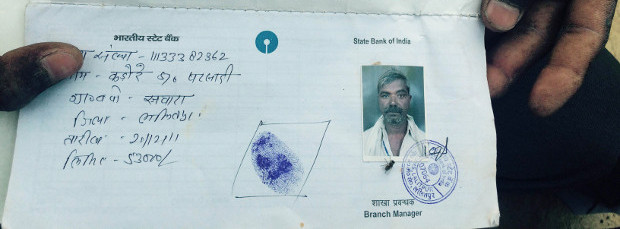

The bank passbook of Kadore Kushwaha, a 56-year-old Uttar Pradesh wheat farmer who failed to repay a four-year debt of more than Rs 41,000. The local administration, which has not sent an official to find out how he died, refuses to acknowledge that such suicides are a result of agricultural distress, blaming them on drinking and disease. Image: Bhasker Tripathi, Gaon Connection

Rajwada (Lalitpur district), Uttar Pradesh: When the unseasonal downpour swept through his land last month, Kadore Kushwaha spent the night worrying. When the rain stopped the next day, he inspected his wheat farm.

He returned, left for the market, bought what his family called “sulphas”, available as tablets, came home and took some.

Kadore, 56, was taken to the hospital, but he died the evening of March 19, his body rapidly poisoned by the fertiliser aluminium phosphide—the scientific name for “sulphas”—a popular mode of suicide here in an impoverished district officially classified as among the 250 most backward in India.

Kadore was under much mental stress, according to his family. Three days before he died, he received a notice from a bank through the local court, warning him to immediately deposit Rs 41,415 plus interest.

It is a debt Kadore failed to repay over four years, during which his crop repeatedly failed.

When Kadore was cremated on March 20 at his village, 5 km from the district headquarters, the local papers headlined his death. But until March 27, when your correspondent visited Rajwada, no official had been there—which means his suicide was not recorded.

Kadore is not the only farmer whose death was ignored by the administration of India’s most-populous state. Farmers' representatives and non-government organisations reported more than a dozen similar suicides in just Lalitpur and Hamirpur, both in south-eastern UP’s backward region of Bundelkhand last month.

The government denies that crop failures and debt pushed any farmer to suicide in these two and 10 other districts ravaged by unseasonal rain and hailstorms in 2014 and 2013—a phenomenon that has occurred again, as we write this, raising the possibility of further distress.

Officials sent out—but do not reach families of the dead

On March 27, Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister Akhilesh Yadav ordered district collectors and other government officials to track down farmers who had died and find out the causes of death.

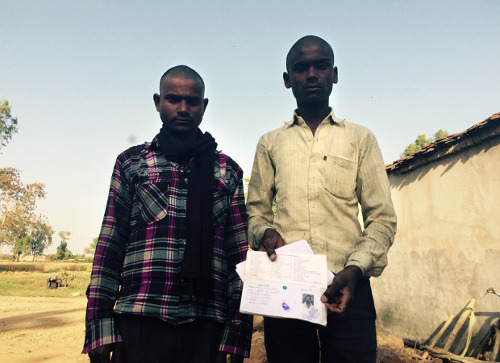

“Where is the officer?” asked an agitated Purshottam Kushwaha, 29, son of the dead farmer Kadore. “No one has come till now, not even the accountant.” Purshottam and younger brother Vijay have abandoned farming and now work as labourers.

Nissar Khan, a worker of Sai Jyoti Sanstha, an village NGO in Lalitpur said that his organisation had visited the homes of four farmers who had killed themselves. “There have been more deaths,” said Khan, “and we are still doing our survey.”

More than 40 suicides by farmers were reported when hailstorms destroyed the rabi, or winter, crop last year, said Khan. “We have all those details,” said Khan. “But in the official data, there is no mention of them.”

After Vidarbha in Maharashtra, long regarded as India’s farm-suicide heartland, Bundelkhand—comprising the districts of Jhansi, Banda, Chitrakoot, Mahoba, Lalitpur, Hamirpur and Jalaun—has emerged as another region where farmers kill themselves, deaths that UP’s government would rather not acknowledge as suicides.

Over 20 years—between 1991 and 2011—more than 1.5 million farmers, distressed by crop failure and death, committed suicide across India, according to P. Sainath, journalist and Magsasay Award winner, who analysed National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) data. The NCRB reports to the Ministry of Home Affairs, collecting data every year from states.

At least 3,000 farmers have killed themselves in Bundelkhand over five years, according to official records and suicides reported in newspapers, the terms of agricultural bank loans that underlie these deaths substantially more unfavourable than home loans given to the urban middle class in India’s metropolitan cities, as IndiaSpend reported in October 2014.

Suicides by farmers—even if you consider only official data—reflect a farm crisis in India, where 118.9 million of 1.3 billion people are dependent on agriculture. If families are included, the number exceeds 600 million.

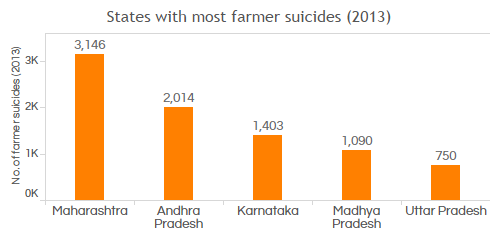

Source: NCRB (National Crime Records Bureau)

Most farmer suicides were reported in states like Maharashtra (3,146 cases), Andhra Pradesh (inclusive of newly formed Telangana, 2,014 cases) and Uttar Pradesh (750 cases) in 2013, according to the NCRB.

Why UP’s data on farm suicides are dodgy

UP, as IndiaSpend reported last month, has a problem with dodgy data, and farm suicides do not appear to be an exception.

Here is why:

According to the NCRB report, UP, with a population of 200 million, had 750 suicides in 2013. However, Madhya Pradesh—a state with two-and-a-half-times fewer people than UP—reported 340 more suicides than UP.

The contradictions in the data—and reports from the ground—indicate that many suicides by farmers in UP are not making their way to official documents.

Farmer representatives accuse local officials of gathering information on farmer deaths but deliberately not registering it.

Chronic diseases, drinking—not suicides: Officials

Gauri Shankar Bidhua, head of the Bundelkhand Kissan Panchayat (Bundelkhand farmer council), firmly blamed district officials for not registering suicides. “According to our survey, until now (March 27), 62 farmers have committed suicide in Jhansi, Banda, Hamirpur, Jalaun and Lalitpur alone,” he said.

Officials attribute such deaths to causes other than weather disasters, crop failures and debt. Anuraag Yadav, the district collector of Jhansi, said he now possessed all the inquiry reports into the deaths of farmers, and crop failure was not a cause.

“Reasons like chronic diseases and drinking habits are coming to attention,” he said.

“We keep fighting with the governments about the facts, but they do not accept that their debts killed them,” said Bidhua. “The weather’s blow to the rabi crop is breaking down farmers mentally.”

Things became worse this time because of a drought during the kharif (monsoon) crop across Bundelkhand—coming on the heels of hailstorms that wrecked the rabi crop in 2013 as well.

That there is a crisis on Bundelkhand’s farms is something the government now acknowledges.

What happened to Bundelkhand’s rabi crop

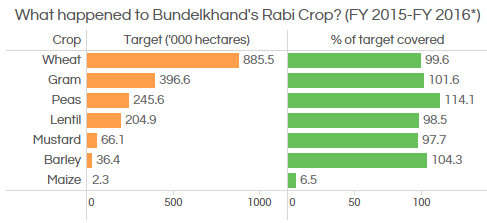

The overall crop production, by area, appears healthy, but drops in key crops indicate localised problems, enough to cause bankruptcies and those suicides.

Source: Directorate of Agriculture, Uttar Pradesh

In Bundelkhand’s seven districts, wheat was sown across 88.19 lakh hectares; 92.2 lakh hectares were sown with pulses (gram, peas and lentil), according to the UP farm directorate.

On March 26, during the budget session, in reply to a question, Chief Minister Yadav accepted that Bundelkhand had suffered from unseasonal rains and hailstorms.

His government, however, will not accept that these disasters could have pushed farmers like Kadore to suicide.

(Tripathi is Senior Reporter at Gaon Connection, a rural newspaper published in Hindi from Lucknow. Tewari is an analyst with IndiaSpend.)

This is the first of a two-part series. You can read the second part here.

Update: This story has been modified to reflect the number of Indian families dependent on agriculture.

__________________________________________________________________________

“Liked this story? Indiaspend.com is a non-profit, and we depend on readers like you to drive our public-interest journalism efforts. Donate Rs 500; Rs 1,000, Rs 2,000.”