As India Fights COVID, 50% Households Share A Water Source, 41% Share Toilets

Bengaluru, Mumbai: Nearly 600 million people face “high to extreme water stress” in India. About 94 million--more than three times the population of Australia--live without a source of clean water, at a time when access to water and sanitation is essential to protect people from COVID-19 or any other health risk.

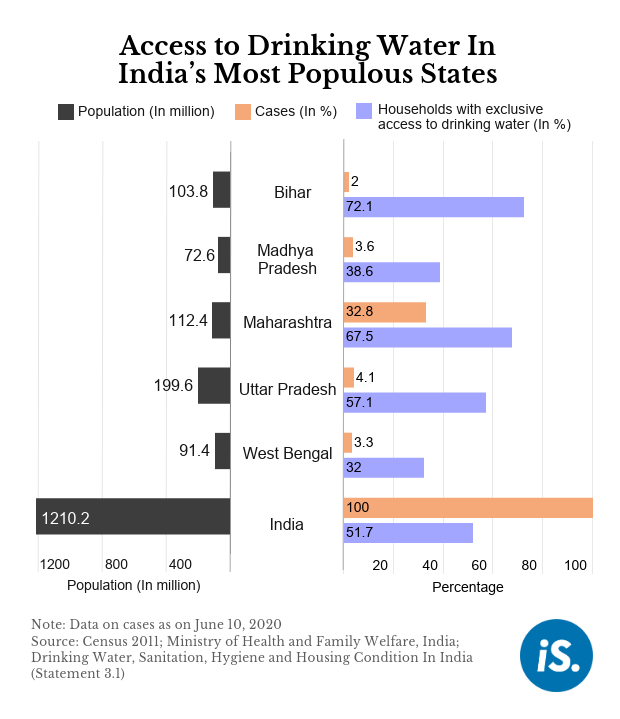

An IndiaSpend analysis of five of India’s most populous states--Uttar Pradesh, Maharashtra, Bihar, West Bengal and Madhya Pradesh--which account for 46% of all COVID-19 cases in the country, as on June 10, 2020, found that lack of exclusive access to drinking water, distance to the source of water, poor sanitation and handwashing habits were a challenge for households. Hence, preventing the infection also becomes a challenge.

In both urban and rural India, lack of water facilities and the need to use community water sources and toilets would pose a challenge in the fight against a disease that currently has no cure and limiting whose spread is contingent upon washing hands and maintaining social distance, experts told IndiaSpend. It is practically impossible to prevent infections through common water and sanitation sources, an expert said, adding that the common facilities, especially in urban slums, have no arrangements for disinfection.

India has had more than 275,000 COVID-19 cases, and reported its highest single-day increase of 9,987 new cases on June 9, 2020, after more than two months of lockdown, which triggered reverse migration to rural regions.

Drinking water availability

Nearly half (48.3%) of the households (in urban and rural India) do not have exclusive access to drinking water and one-fourth of households access it through a public, unrestricted source (23.6%), data from the National Sample Survey’s (NSS) 76th round (2018) show. In rural areas, less than half (48.6%) have exclusive access and 30.5% access public sources.

A family of four would need 40 litres of water--same as the government's allocation per person per day in rural areas--to wash hands if a conservative estimate of two litres is used for each hand wash, as IndiaSpend reported in April 2020.

“A high dependence on community stand posts and community toilets has both contributed to increased probability of exposure to the virus,” said V.K. Madhavan, chief executive of WaterAid India, a non profit. “Uncertainty over availability of or inadequacies in water supply that existed before has made practising hand hygiene that much harder for those residing in slums in urban areas. Increase in cases in urban areas where poor live are exposing the fault lines that exist [in India].”

“It is possible that demand [for water] during this period may go up and if people have to fetch water from the public stand post, supply hours may be required to be increased to ensure social distancing,” the health ministry said in an April 14, 2020 advisory, issued following a Supreme Court order for a writ petition on need for clean water.

While nearly two in three households in India have a source of drinking water at home or within the premises, the rest (34%) have to travel to access water, some of them more than 1.5 km, according to NSS data. Maharashtra, the state with one-third of all cases in India, reported that 21% of households need to travel outside their homes to a source of water. Bihar was the only state, among the five most populated states, where fewer than 10% of households had to travel to a principal source of water.

Of the five states, more than two in five households (rural and urban) in Madhya Pradesh (44.8%) and West Bengal (46.5%) depended on a public, unrestricted source for drinking water.

Among rural households, more than half in Madhya Pradesh (57.5%) and West Bengal (50.1%) had to use a public source for drinking water. The percentage was lower in Maharashtra (23.2%), Uttar Pradesh (21.3%) and Bihar (4.7%). Bihar has “chappakal or hand pumps just outside each house, often, even inside homes”, said Sunderrajan Krishnan, executive director of the Indian Natural Resource Economics and Management (INREM) Foundation, a research institution that looks into societal issues concerning water, public health and environment. Northern parts of Bihar “have a much shallower water table than those in these other states”, he added.

Water scarcity

Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, West Bengal and Bihar are among the states that have received the highest number of Shramik Express special trains since inter-state movement of people was allowed on May 4. These states have reported between 70% and 90% of their total number of COVID-19 cases since May 4. Of these, Bihar (91%) reported the most, followed by West Bengal (90%), Uttar Pradesh (77%) and Madhya Pradesh (71%).

It has taken a few months for the pandemic to reach the most remote parts, said Krishnan. “Now, the harsh reality of poor access to water facilities and lack of health facilities and detection in rural areas is coming to the fore. It is going to be a very tough two to three months for some of these pockets which will emerge as the newer hotpots of COVID-19 in rural India,” Krishnan told IndiaSpend.

It would emerge that these same households who “do not have access to hand-washing facilities also do not have the luxury of maintaining physical distancing because of the nature of their livelihoods and occupations”, added Krishnan. “This population is highly vulnerable. Surely, there is a big hidden water scarcity now. It has not received any attention because of the COVID-19 crisis... people are coping silently.”

“Due to fragmentation of areas [with lockdown restrictions making routes inaccessible] and containment measures, it is not even possible now to access water sources far away,” said Krishnan. “Containment measures also mean some people have to take longer routes to fetch water.” This also means that there is an added burden on women to collect water. Worldwide, 200 million hours or 22,800 years are spent by women and girls every day in collecting water, noted a 2016 United Nations press release.

“Due to COVID-19, there is a need to collect more water. Due to inadequate storage capacities at home, several women and girls have to undertake more trips to collect water, further aggravating their physical distress,” said Chandra Ganapathy, head of knowledge management at WaterAid India. While communities are following physical distancing at public water sources using paint, lime and old cycle tubes as markings, “the challenge is to inculcate the habit of sanitising the handles, [or areas] where there is contact at water collection points regularly and properly”, Ganapathy added.

For 30.5% of Indian households, a hand-pump is the source of drinking water, NSS data show. The number increases by 12.4 percentage points in rural areas. Except for rural Maharashtra (8.9%), more than half the rural population of the other four states--Bihar (94.3%), Madhya Pradesh (52.4%), Uttar Pradesh (87.8%) and West Bengal (53.8%)--gets water from handpumps.

“We find rural communities asking us to [provide] tankers in many places. They are unable to make arrangements these days due to the local permissions needed for movement,” said Krishnan. India is the world’s largest groundwater extractor, accounting for 12% of global extraction, as IndiaSpend reported in June 2019.

Better communication for improved hygiene

Only one in four rural households in India use soap and water to wash hands before a meal, while one-third wash their hands with sand/mud or only water after defecation, NSS data show. Overall, only 35.8% households wash hands before a meal and one-third households in rural India do not use soap or detergent to wash their hands after defecation.

Although early studies have shown evidence of COVID-19 genetic material in faecal matter, more research is needed to determine if the virus can spread through stool, according to an April 2020 study in the International Journal of Infectious Diseases. However, when shared facilities are used by infected individuals, they “could become sources of both airborne and contact exposures to SARS-CoV-2 exposure, especially in the absence of adequate water and soap for hygiene purposes,” public health researchers from Emory University in the US wrote in The Lancet.

The behaviour change around handwashing hygiene needs several rounds of reinforcement, which is difficult at scale, said Krishnan. “There has been a sense of awareness building up and more tendency towards hygiene and handwashing, but this is observed in places where focussed communication and interventions are happening,” he added.

There has been a change to “some extent” as people are using “soaps, detergents and washing powder to wash their hands and [a] negligible percentage is also using sanitisers where water supply is a challenge”, agreed Ganapathy, adding, “But there is a lot of scope for improvement.”

At 42.9%, Maharashtra had the highest number of rural households washing hands with soap before a meal among the four states, followed by Madhya Pradesh (26.6%), West Bengal (18.6%), Uttar Pradesh (16.9%) and Bihar (12.2%), as per NSS data.

Community sanitation facilities and risk of infection

Community toilets and sanitation facilities pose a risk as it makes social distancing and hygiene difficult. In densely populated cities and slum pockets like in the case of Mumbai, “presence of overused and poorly maintained mega community toilets are seen to be the ‘major reason’ for the explosion of Covid-19 cases in the city”, noted a May 16, 2020 feature by Observer Research Foundation, a think-tank.

In India, 41% of households use community bathrooms, 11.2% use community latrines and 20.2% have no latrines, NSS data show. Among the states analysed, all except Maharashtra had more households using community bathrooms than the national average. In West Bengal (63.7%), Bihar (63.1%) and Uttar Pradesh (62.2%), nearly two-thirds of the households had no exclusive access to bathrooms.

Nearly 38% of households in Uttar Pradesh and 33% in Bihar do not have latrines. At 22.5%, Madhya Pradesh also had a higher proportion of households without latrines than the national average. “People from households without a toilet are most likely to defecate in the open,” said Ganapathy, adding that if transmission of COVID-19 through the faecal-oral route were to be established, then the prevalence of open defecation will add to the risk in rural India.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi declared rural India open defecation-free on October 2, 2019. But, a FactChecker.in investigation across five states found missing toilet subsidies, half-constructed and neglected toilets, lack of water in toilets and open defecation.

“Even in households where toilets and bathrooms exist, the load may be very high [due to the recent reverse migration] and it may become difficult to maintain proper hygiene and sanitation,” said Ganapathy. “This may be increasingly important in the case of confirmed COVID-19 patients and those in home quarantine.”

While rural areas with lower population density have the advantage of physical distancing and isolation, the nature of water and sanitation systems in urban areas and the habitations themselves put the urban poor at much greater risk, said Ganapathy.

Of the 276,583 COVID-19 cases in India, 18% (50,878) are in Mumbai, home to 44% of the slum population in Maharashtra. In Dharavi, one of Asia’s largest slums by population, 1,621 cases were reported till May 26, 2020--when data were last shared by the municipal corporation. Of the 35 states and union territories that have reported COVID-19 cases, 17 have fewer cases than Dharavi.

A Union inter-ministerial team that had visited Dharavi in April 2020 found that many residents have to step out of their houses in violation of lockdown restrictions as most of them use community toilets. The team had suggested arranging portable toilets for the residents.

(Paliath is an analyst and Shreya Raman is a data analyst with IndiaSpend.)

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@indiaspend.org. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.