‘Climate Change Impact On Health Isn’t Easy To Perceive, So It Doesn’t Resonate With Populace’

New York: In Katowice, a Polish city whose economy has always rested on coal production, world leaders sat down last month to work on a framework on how to move forward with the 2015 Paris Agreement that aims to contain global warming below 2 degree Celsius.

The leaders who are a part of the 24th Conference of Parties (COP)--the highest decision-making body of the United Nations Convention on Climate Change--aimed to put in place measures to safeguard the health of our planet.

As many as 600 million people in India are at the risk of fallouts from climate change, most of them involved in agriculture or fishing. The 1-degree-Celsius rise in global temperatures has already caused the Himalayan ice sheets to melt at a fast pace, threatening the water supply to the rivers that depend on them. Rising sea levels have already changed lives and affected livelihoods along the country’s coastline and the prospect of conflict looms large.

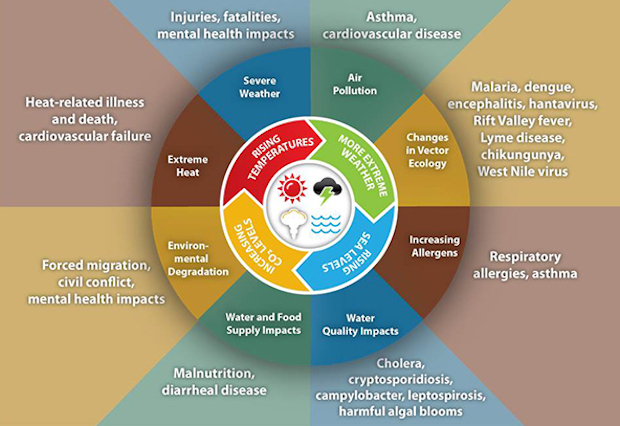

But, apart from the directly observable impacts on livelihoods, climate change is also likely to affect the spread of infectious diseases and nutrition levels of the crops, among others. The IPCC report by the UN, released in October 2018, warned that an increase in global temperatures would lead to a rise in heat-related adverse conditions and deaths. It also warned of a rise in vector-borne diseases such as malaria and dengue fever.

Climate change has already had negative health effects and undermines the “right to health”, especially among the poorest and most vulnerable communities, widening health inequalities, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). The direct damage costs to health are predicted to be between $2-4 billion per year by 2030, more than the entire gross domestic product (GDP) of Bhutan. Exposure to air pollution alone causes 7 million deaths every year worldwide.

IndiaSpend spoke with Jeffrey Shaman of the Mailman School of Public Health in New York, where he is the director of the climate and health programme, on how climate change impacts our health and why it is so difficult to link a particular public health event to climate change.

With a background in climate, atmospheric science and hydrology, as well as biology, Shaman studies how atmospheric conditions impact the survival, transmission and seasonality of pathogens. He is also interested in how meteorology affects human health. Shaman is currently working to develop systems to forecast infectious disease outbreaks at a range of time scales using mathematical and statistical models.

Edited excerpts from the interview:

There is clear evidence that climate change is having a serious impact on human lives and health, as per WHO’s director general Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus. What kind of public health impacts are we talking about?

It is going to be varied and some of it will be very subtle. I think you need to think of the climate system as a stressor on other systems, some of which affect health. You can break it down into those three components--the direct effects, the indirect and sort of more complex downstream effects.

In some instances, it is going to be like the heatwaves that are going to be more characteristic, more frequent and more intense. There are going to be times of the day potentially, not too far distant future, where certain parts of the world are not going to be hospitable outside because nobody’s going to be able to cool off.

It certainly is going to have other effects that might be more indirect that might be mediated through ecological systems, natural systems and other biological agents, things like infectious diseases that people often talk about, changes in allergens and pollen seasons. It is going to have more complex effects that may be associated with fossil fuel combustion, changes in air pollution and changes in ability to grow crops, maintain food security and water security.

If you are thinking about the outcomes, they run a whole gamut of problems--everything from infectious diseases to exacerbation of non-communicable diseases, cardiovascular problems, pulmonary issues, neuro-developmental issues, developmental issues, issues directly associated with temperature, heat-related morbidity and mortality, changes in pollen levels and things that are going to exacerbate chronic conditions of the lungs, COPD [chronic obstructive pulmonary disease], asthma etc.

There are going to be mental health issues associated with it and that can be everything from people being overwhelmed by what is happening and the changes in their life due to forced migration and having to abandon low-lying lands to how do you deal with mental illness services in places that are hot. What is that going to do to people who are really in the harm’s way and not able to take care of themselves?

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

During the COP24 meeting in Poland, the WHO drew attention to how only 0.5% of the multilateral climate finance has been specifically assigned to health projects. It also highlighted how climate change already has negative health effects and undermines the “right to health” especially in the poorest and most vulnerable communities like small-island states. Is the stress on public health impact of climate change enough?

It’s late. Whether it is too late or not I can’t tell you. I would have loved to have seen action on all this 25 years ago on a global scale.

Did we have evidence back then?

Oh yes. There was a substantial amount of evidence. People have said that the evidence is better now, and it is, but the question is when do you act on it? The big problem is, and this gets to sort of why we have not been able to act about global warming, we had the Montreal Protocol and the thing about it is there was a ready solution (countries decided to phase out substances that depleted the ozone). There was an alternative that you could plug in, that could be easily manufactured, that wasn’t going to compromise the ability of the people to do the same thing that they’ve been doing before. The pain associated with signing on to that protocol was not great. The consequences were good as a result of that. We don’t have that easy answer for climate change. Climate change is pushing against the interests of a lot of interests--oil, gas, coal, electrical power, car industry--all these components. The way we go about things, they have to undergo a major restructuring.

The very existence of some of these corporations would disappear. Some of these won’t survive the transition. What you are asking for is a transition. What you are asking the societies to do is to change the way they do business. In some way it’s happened. It could have happened faster with taxes and regulatory actions. Regulatory actions are very effective when properly implemented and they do compel and initiate a lot of innovation rather than let them happen otherwise. But the problem here is that nobody had the appetite for it.

Where does the willpower come from? The willpower has to come from the people. People respond to things that sociologists tongue-in-cheek call the three S’s. Things that will happen soon, certain and salient. Obviously, they are not all S’s. If it is going to happen immediately, if it is definitively going to happen and if the impact of it is going to be felt then people will act on it. Climate change is not all of those. It is none of those. It is a gradual creep. It is not certain--none of us knows how bad it is going to be, if it is going to be bad in your location. It is not salient.

Yes, you can have a hurricane and cyclone come about in some communities but then people quibble about the fact that they’ve have them before. Attribution is very hard. Climate change is not in the appropriate place that the general populace is going to prioritise over the health of their family etc.

What about human health? Health and the impact of climate on human health are things you think might motivate people into action but it doesn’t. It just doesn’t seem to resonate for most part. Again, it’s this attribution. We’ve had hurricanes before, we’ve had droughts before. It is going to be the accumulation of evidence, disaster after disaster when people really start to recognise that there is a decided acceleration in the number of things that are going wrong.

Waiting for people to perceive it is just not the way to do it though, because we can’t perceive climate change well.

The WHO video explains the impact of climate change on health services in South East Asia.

We are seeing a fresh outbreak of zika in India, not a disease heard of in the region. What role will the warming planet play on the spread of such infectious diseases to newer regions and their absolute numbers, if at all?

Zika obviously is vector-borne and there are going to be changes in the environment that are potentially going to be beneficial to the Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus (mosquito species that spread zika). Those are climate-sensitive diseases in the sense that the mosquitoes themselves are climate-sensitive. You are already (in India) in an environment where these mosquitoes can survive.

I think certainly within India there is some possibility of climate drivers associated with zika but I again put this cautionary on which is that there are a lot of other drivers of a disease, and you can’t look at a disease in isolation. Why you get a disease outbreaks have to do with prior exposure and immunity. If you have a population where everybody is already immune to zika you are not going to see an outbreak because no one is going to come down with it. If the population is completely susceptible then you will see large outbreaks of zika. It comes down to infrastructure. You are going to see them in areas where the mosquitoes are more likely to breed such as slums where there aren’t good screens in the windows and where there is standing water available in pots that can be breeding spots for mosquitoes.

A vector is any organism--such as fleas, ticks, or mosquitoes--that can transmit a pathogen, or infectious agent, from one host to another. Warmer average temperatures might make it easier for some vectors to reproduce leading to a rise in vector-borne diseases.Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

So those conditions in themselves are more socio-economic than anything else that can lead to disparities where you will see more zika in communities that are more impoverished.

You have to be careful to not say this is a global warming symptom. This is a signal or even a climate variability signal. Maybe the monsoon was really wet that year. Attribution of individual events is always the place where it gets really sticky. What I will say is that it is another stressor. I cannot tell you right now that the drought caused the Syrian civil war. You have all sorts of other socio-economic and political drivers of what’s going on there. Did it lead to crop failures that could have exacerbated the problem? Yes, it did. Absolutely. Are those crop failures linked to the weather? Yes, they are. Are the weather events related to climate changes? I think so.

I am getting a little more tenuous as I am going back but I still think the connection is there and I still see it. We have seen it too many times and it seems to increase over and over. It is with that lens that you have to step back and say that zika doesn’t occur in isolation. Infectious diseases are all around the world and they are certainly still prevalent in India. So, the fact that you have a zika outbreak could mean it is the introduction of the virus or the reemergence of the virus.

That makes it more difficult for the policy makers to act, does it not?

Right, because I have just undermined the certainty of that. It makes it very difficult when you can’t attribute them. A policy maker is not going to want to implement a policy because it is unpopular and doesn’t have a clear reason for doing it with demonstrable outcomes that are beneficial.

But we have to look at the collective evidence and the collective evidence suggests that it is happening, it is not immediate--that’s problematic. And the ways it’s going to be manifesting are many. So, we have this multi-tier outcome that we are going to have to content with that’s destabilising in many ways. We like a certain amount of stability in our life.

What would mitigation for a city like Mumbai for instance look like?

There are all sorts of policies you can implement. Trying to plant trees, regulations and controls on the way fuels are going to be burnt. Obviously, the burden of doing that is going to be very different in a city such as Mumbai. It is somewhat modern but it is a complicated system right now. It is less centralised and it doesn’t even provide piped water to all of its citizens and some of its citizens aren’t even official. So, in a situation like that there has to be roles for regulation and community effort, trying to do it from bottom up rather than top down I would think.

(Disha Shetty is a Columbia Journalism School-IndiaSpend reporting fellow covering climate change.)

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@indiaspend.org. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.