COVID-19: India Must Regulate Its Wildlife, Wild Meat Markets

Bengaluru: India must regulate its numerous markets that sell wild meat and live wildlife--especially in the wake of COVID-19--by regulating the trade, addressing the social and economic reasons that drive people to trade in wildlife, and safeguarding and restoring wildlife habitats, experts have told IndiaSpend.

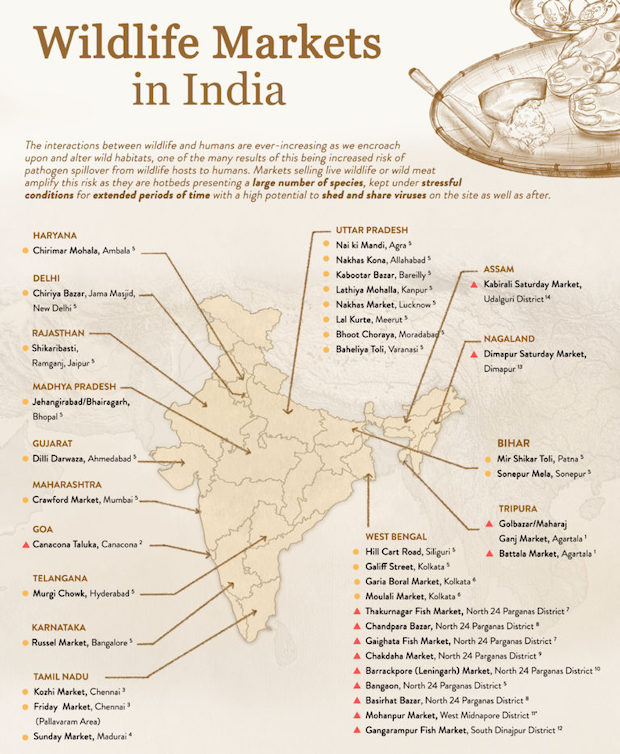

Numerous such markets exist around the country, according to a report by Wildlife Conservation Society-India (WCS-India), a non-governmental wildlife conservation organisation, published in April 2020. These markets amplify the risk of zoonoses--infectious diseases caused by pathogens that jump from animals to humans--because they house a large number of species under stressful conditions for extended periods of time.

To understand what happens if such markets are not regulated and illegal trade in wildlife is not curbed, one needs only to look at the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

About two-thirds of the first 41 patients admitted to hospitals with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 infection had been exposed to the Huanan seafood market, “an important hub in the lucrative trade in wildlife--both legal and illegal”. Scientists believe that this poorly regulated, unsanitary market has all the conditions that are conducive for virus transmission from animals to humans.

As of June 9, 2020, more than 400,000 people have died of COVID-19 globally, with over 7 million confirmed cases, data from the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center show. India has reported 266,598 cases, and 7,466 patients have died, according to Coronavirus Monitor, a HealthCheck database.

At least 60% of about 335 identified diseases that emerged between 1960 and 2004 were transferred from animals to humans. Zoonotic diseases are responsible for 2.5 billion cases of human illness and 2.7 million deaths worldwide each year, as IndiaSpend reported in March 2020.

Where these markets are

Source: Wildlife Conservation Society-India (WCS-India)

The representative map is based on information openly available online that was collated and assessed by members of WCS-India’s Counter Wildlife Trafficking (CWT) Program. The aim is to improve capacity among enforcement agencies to detect, identify, investigate, arrest, prosecute and convict wildlife traffickers.

“As you can see from the map, markets where wildlife is sold are widespread across the country,” said Sahila Kudalkar, who leads WCS-India’s CWT programme. “But I suspect that this map represents only a snapshot of a much more pervasive problem across India,” she added.

“The dynamics of wildlife trade are changing,” said Jose Louies, a conservationist with the Wildlife Trust of India, a Noida-based conservation organisation. “In the last few years, we have not found large, organised tiger poaching networks. But live animal markets, especially in small mammals and reptiles like turtles and tortoises, are booming and even local [wildlife] meat markets are becoming a big problem.”

Not new

“Urban markets such as those in Mumbai, Delhi, Chennai and Kolkata have been selling wildlife for many years and continue to do so,” Kudalkar said. She explains the high incidence of such markets in Uttar Pradesh and West Bengal on the map is probably owing to a reporting bias. “It is also important to remember that both these states are critical nodes in the international freshwater turtle and tortoises trafficking network.”

“A large volume of freshwater turtles and tortoises are collected from across the extensive river basins of Uttar Pradesh and these animals then make their way to markets in West Bengal where they are sold to customers,” Kudalkar explained. “Often, West Bengal is just a pit stop for species such as spotted black terrapins which are then transported across the land border to Bangladesh, or sent to southeast Asian countries by air.”

Many cities in Uttar Pradesh also sell protected native birds such as parakeets, munias, owls and hill mynas.

For smugglers, wildlife may also be considered as “just another commodity worth trading, besides other contraband such as drugs, weapons, artefacts”, said Aristo Mendis, lead wildlife crime analyst of WCS-India’s CWT programme. Such trade is prominent in areas that are in proximity to international borders “which makes it important to focus on such regions to counter wildlife trafficking”, added Mendis.

But first, a thorough assessment of the prevalence of wildlife markets in the country is needed, especially given that we are living through a zoonotic pandemic, said Mendis.

To get a truer picture of the scale and impact of wildlife markets in India, researchers could merge data on wildlife crime sourced from multiple enforcement agencies, government and non-government organisations, media outlets (including local, regional, state-level and multilingual news sources), as well as other relevant information portals, Mendis suggested.

Most aware trading wildlife is illegal

Wildlife crime syndicates operate at varying levels--regional, state, national and international--and there are multiple players involved. Hence, it is difficult to ascertain how significant each player is in any organised illegal trade syndicate.

For example, a July 2019 raid on a rhino poaching syndicate in Assam revealed the role that the master of the ring played in facilitating the trade by hiring ‘sharpshooters’ from the northeastern states and supplying them with the necessary guns and weapons. The ‘master’ was also instrumental in moving rhino horns from the poaching site in Assam to Nagaland and Manipur, from where they were smuggled to neighbouring Myanmar.

A September 2019 investigation into the pangolin smuggling network found that “there is clear indication that some individuals within the syndicate play a significant role in facilitating the trafficking, and who are clearly aware of the illegality of trade in wildlife”, said Mendis.

“In my experience, most people are usually aware that selling or buying wildlife is illegal,” said Kudalkar of the CWT programme. “In places like the Battala market in Agartala, the local authorities have put up signboards warning against the sale and consumption of wildlife, but the sale of freshwater turtles and tortoises continues.”

How to crack down on smuggling

The Suraj Pal case shows what strong enforcement action can do, Kudalkar said: the accused was convicted under stringent provisions of the Prevention of Money Laundering Act, 2002 (PMLA), which empowers the authorities to freeze assets, effectively choking finances of wildlife smugglers. “Charging offenders under the PMLA can go a long way in dismantling organised trafficking networks,” said Kudalkar.

Better communication between various offices and agencies involved in cracking down on wildlife protection and smuggling could lead to improved detection of crime and stronger action against offenders. “In the past year alone, we have had numerous instances where we facilitated communication between officers from the state forest departments and security forces, such as Border Security Force and Sashastra Seema Bal, leading to successful action in cases involving turtles, tokay and geckos,” said Kudalkar.

The key in an enforcement-driven solution is regulation of the trade--rather than the blanket ban we currently have in place. “Overnight, the Wildlife Protection Act (WLPA) outlawed the hunting and consumption of wild meat, irrespective of whether it came from an endangered species or a common one,” said Abi T. Vanak, a senior fellow at the Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and Environment, a non-governmental organisation that works on conservation and sustainability.

Except for a handful of species that are listed under Schedule 5 of WLPA as “vermin”, it is illegal to kill and consume wild species.

“Even in the case of species that are declared agricultural pests in some states and are allowed to be shot, like wild pigs or nilgai, in most cases their consumption is not allowed. This goes against every tenet of sustainable harvesting,” noted Vanak. “There are clearly good reasons to not allow the hunting or killing of endangered species, but what of species such as chital that are protected on the mainland but are an invasive species in the Andaman islands and cause great harm to the native vegetation?” asked Vanak.

However, it is important to note that allowing hunting of certain wildlife might entail enforcement issues in the conservation of all other wildlife. “It is difficult to say what animal was killed, especially if what we have left is meat… may be cooked meat,” said an enforcement officer on condition of anonymity.

“To ensure that people do not become a part of the wildlife trade, we have to address other questions like: Is poverty driving people to trade in wildlife? Is hunting a part of local culture and tradition, and is the sale of wildlife in local markets opportunistic in nature?” said Kudalkar. “Of course, the first step [to tackle illegal wildlife trade] is strong and direct enforcement action, but multiple social and economic interventions are likely required in the long term,” explained Kudalkar.

As for the larger issue of safeguarding and restoring wildlife habitats, what India can do is secure wildlife corridors, strengthen legal frameworks, and completely ban big developmental projects such as mining and hydropower within protected and other ecologically sensitive areas, added Kudalkar.

(Pardikar is a freelance journalist from Bengaluru.)

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@indiaspend.org. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.