'There Is No Timeline But Watch For Symptoms Worsening, Then Seek Hospitalisation'

It is becoming increasingly difficult for acutely ill COVID-19 patients to find hospital rooms, oxygen and medicines. What is the best way to deal with the progression of the disease? We speak to two doctors

Mumbai: The number of reported COVID-19 cases in India in 24 hours has now crossed 332,000, the highest for any country in the world at this point, and in the pandemic's history. The COVID-19 we are now seeing is a little different from what we saw in 2020: A lot of younger people are being infected and also showing more severe symptoms than before. The disease is also far more infectious than before.

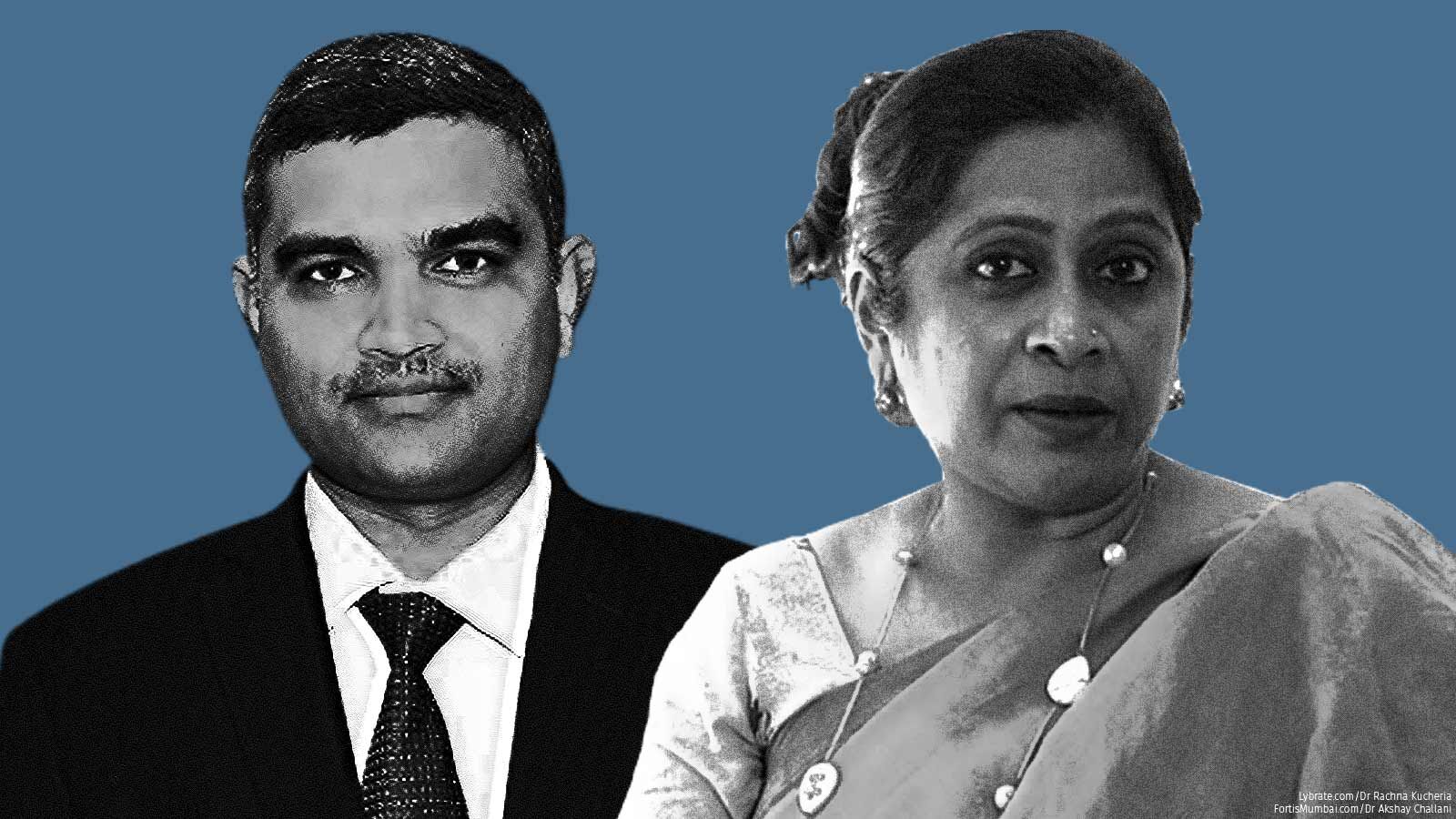

With the medical infrastructure collapsing across India and shortages in medicines and oxygen and hospital beds, what should patients be doing? How do they know that they have crossed the point where home care is no longer enough? We put these questions to two experts--Rachna Kucheria, the founder of DocGenie Telemedicine and Technologies and also an MD in family medicine, and Akshay A. Chhallani, a physician and intensivist at the AkshJyot Clinic and also with Apollo hospitals in Navi Mumbai.

Edited excerpts:

Dr Kucheria, how has the pandemic changed in 2021?

RK: We're seeing a much more infectious variant. This is what I'm hearing from patients over and over again: "My parents haven't stepped out of their house for over one year and yet they're infected." Whole families are down--it's rare for only one or two persons to be infected in a household [unlike in the first wave]. That is one of the biggest differences we're seeing.

In terms of symptoms, there is much more drying of the mucous membrane passages. People are complaining that [it feels like] there is something stuck there. People do different things to mitigate this, but actually it is the virus acting up. The other most common symptom I am hearing is a lot of weakness--even in young, very fit people who are the sort that play or exercise daily, even making a cup of tea becomes hard for them. And I do talk from my own family experience where four people are down.

Dr Chhallani, between last year and this, what are the key differences in the demographics of those who are contracting the virus?

AC: This year, we are seeing more younger patients. Last year, patients were more in the fifth or sixth decade [of their lives], but this year we are seeing the people in the third or the fourth decade. Secondly, last year we did not see much of a fever lasting one week or more; it lasted two to three days and the patient either landed in the hospital or did well. But this year, by and large, over the last two to three months we are observing that the fever lasts beyond a week. And after that they do recover, while some who have comorbidities such as diabetes or hypertension end up in the hospital. The third thing is that now we have a [better] grip on the situation compared to last year. We are in a better position to treat people because we know the nature and course of the disease.

Let's come back to those first few days of the illness. Dr Kucheria, you spoke of that feeling of a scratchy throat. What happens after that? And at what point do most people tend to either take the next right step or lose control?

RK: Just to piggyback on Dr Chhallani's point, the fevers are longer this time, I would say [lasting] even up to 10-12 days. People shouldn't panic.

The progression usually starts with a very mild sort of what doctors call a URI or upper respiratory infection, a term for all kinds of viruses--maybe once in a while a bacteria--that all of us have faced, this little (pretend cough), and then you have this burning [sensation in the throat] and a little bit of that feeling of being unwell. In a pandemic, that should raise alarm bells right away--not in terms of panic, but to go isolate. With the whole system--including the testing system--collapsing right now, early recognition of symptoms should be the new testing to mitigate the wave because we can't wait for the results. That should be a very important message. You start feeling the symptoms, isolate, or you are going to infect other people.

So, this fever comes on and starts becoming worse. It could hit 102-103oF and then usually in a couple of days, for most people, the fever also starts coming down. One has to be patient through this time. Look for other red flags to decide if the patient is okay to be kept at home and ride through the fever. In most cases, the fever does come down and other problems like weakness and bodyache start to reverse. The URI, the cough, this dryness may progress. There may be some feeling of a little bit of heaviness in the chest and we have ways to mitigate that--[get people to] lie on the stomach, lie on the chest. As long as we have some amount of reversibility, you know it's getting better. We will come to oxygen monitoring a little later. A small minority of cases also have gastric symptoms--nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea. But 80% are coming with an upper respiratory infection.

Dr Chhallani, would you concur then that for the first five days after you experience the first round of symptoms, nothing much can, perhaps even should, be done?

AC: Yes, basically, for the first five days, we need to mostly watch out for symptoms like fever and weakness. Check if other parameters like pulse, blood pressure are okay--generally the pulse in an adult is around 60-100. So at any point if the pulse is between 60-100, don't worry, but anything above a 100 is a red flag. For the oxygen level, if it goes below 92 or 93, it is [also] a red signal.

What I suggest is that even if you have a mild fever or even if you are around a lot of other COVID patients, when you start any medicine, please consult a doctor. Don't self-medicate. It's not always possible that you have [only COVID], there may be other things in addition to--or instead of--COVID too.

Whenever the oxygen level goes down--since there are a lot of issues with [hospital] beds--until you get a [hospital] bed, try to sleep prone, lie on the stomach, ulta.

You said that there are other conditions which could also be leading to the same symptoms at this point of time. Could you tell us what you have been seeing or have seen?

AC: Specifically talking about Navi Mumbai, in addition to the fever caused by COVID, there is dengue fever, tuberculosis and other viral infections. So don't assume that if you have a fever, that is COVID only. Rule out other infectious diseases like dengue, malaria, typhoid fever and other nonspecific viral fevers.

Dr Kucheria, the heaviness linked to breathing and the lungs, does that usually show itself along with the feeling of discomfort in the throat?

RK: There is this joke going around on WhatsApp that you see every symptom except those for pregnancy and fracture in COVID. I know we would like to really slot these first five to seven days [of the disease] but unfortunately, it's not like that. This virus has us all on our knees. So if somebody started out with mild symptoms and they are continuing [to do so on] day 4, day 5, I tell them, rest assured, you had a good start; because panic and fear--I hope we also talk about mental health issues also--is also something we have to address in parallel.

But for others, on the second or third day they may start getting shortness of breath, difficulty breathing or the oxygen may drop to 90-91 within the first two days. It's a minority [of cases], but there's no timeline. One essential point is that a pulse oximeter, as Dr Chhallani also said, is now essential home equipment like a thermometer. You have to have it, you cannot wait for it because it may be the differentiator between you being able to stay home [and recover] and being sent to the hospital.

Coming to hospitalisation, I think it should be emphasised that no two patients are alike and symptom progression cannot be alike though it may be similar. So if the patient reaches a point where it clearly looks like they have to be taken to a hospital--anywhere between, let's say, four to eight days--what do you then recommend?

RK: This is the really hard part. Do remember the patient pool is different for Dr Chhallani and me. I'm a community health physician and a GP [general practitioner] and he is a hospitalist and intensivist. So, those who come to us are different.

Thankfully, only a small percentage of my patients are in need of hospitalisation. I do mostly telemedicine now but with training and experience you can pick up the red flags--looking or feeling sickly, or breathing issues of any kind. Of course, [with patient] data you can see if the oxygen is down, the temperature is spiking and if that is in combination with anything else. Then one does recommend [that they start looking for a hospital bed]. Even if they are vomiting so badly that they can't keep anything in. Even just the sign that I'm feeling just so sick and miserable--that is a good indicator and should not be negated.

Being able to thread out the unnecessary and the panic from the patient's physical symptomatology is an art or skill. If you start seeing those red flags, I say please start looking for a bed. In the meantime, certain other things can be done but please start looking for a bed. This is really important.

Dr Chhallani, at what point should one think of or even start looking for hospital beds, which are now scarce? And what about sourcing remdesivir?

AC: Unfortunately now, that is the reality. It's very difficult to get a bed because the number of beds and patients is very disproportionate. So what I suggest to those who require a bed is that they make enough attempts to find a bed, not go to the hospital first. I have seen that some patients say they want only this hospital and not that. Don't be very categorical about the hospital because by and large, the government of Maharashtra and all over India, there is a fixed protocol for all COVID-positive patients. So, by and large, the treatment is the same.

What you need to do till you get a bed is drink a lot of water because COVID creates dehydration in your body. Lie on the abdomen. Stable patients can be managed at home. We don't hospitalise them as medical personnel.

Regarding remdesivir, medical literature is very clear that it will decrease the viral load but it does not change the mortality. So don't feel guilty that your patient may not live or do well because you did not get remdesivir.

A lot of people are looking for oxygen as well. Should oxygen be a substitute for going to the hospital or is it something that you need to now arrange even as you go to a hospital because they are running out of it?

AC: This is a grey zone. My suggestion is that if you require oxygen, it is better that you are not at home [but in a hospital], because oxygen is only a component [of the treatment]--you don't know what the patient's pulse or BP is and what their breathing pattern is. If you are breathing very heavily and the oxygen is normal, that's bad. And if your oxygen is on the borderline, but your breathing is comfortable, that is okay. So, in addition to the numbers, breathing pattern, oxygen level and other parameters are also important [to take a call on the need for hospitalisation].

So should you keep an oxygen cylinder at home? My suggestion is that you keep oxygen at home, but make enough attempts to go to the hospital if you require it. It shouldn't happen that there is oxygen at home but you don't make an attempt to go to the hospital because the fact that you require oxygen may mean that you may be in trouble.

Dr Kucheria, on remdesivir, what do your interactions with people show? What are you telling them about oxygen that everyone is now trying to arrange one way or the other?

RK: I agree completely with Dr Chhallani that this whole panic and guilt around remdesivir needs to go. It's good if it [remdesivir] is used in the first two or three days, but remember it's not cutting mortality. That's what we saw in the trials. If it was of any use at all, it was maybe in just cutting some hospitalisation days. There is so much panic and guilt and madness running around for this when our energies could be focused elsewhere. I think it's a bit much. So the correct messaging on remdesivir needs to go out there. And people need to know that we still don't have a drug that kills the [novel] coronavirus. Lots of cocktails are being tried out there, but we don't have evidence-based data that this is actually good. We have drugs for malaria or a sore throat, but we don't have a drug [for SARS CoV-2].

A lot of [drug] cocktails have been given and some very dangerous ones. So please stay away from this. Also support your practitioners by not harassing them--[complaining] that your treatment is not working, you are still running a fever. That's a part of the illness. Remember we are all stretched to the limit. I'm sure Dr Chhallani is, and many of my colleagues are, constantly triaging; the sickest one is getting our attention first and if you have a little bit of fever, that's going to be okay. Right now, it's a war. Support us. Don't point fingers that your treatment is not working. There is no treatment. No one's keeping anything from anybody. If we have a drug, trust me, it would be our job to give it to you first. Especially as a person who manages patients at home, I don't want to give you unnecessary drugs that will give you side-effects and then I have to look after that also.

So really, eating home-cooked food, hydrating, being prone, being with a little bit of peace and joy, meditating, making yourself less anxious--this is the best you can do. And if you're in the care of a doctor, be frank with them, help them assess you for danger signals, and then appropriately start looking for a hospital bed.

You talked about mental health earlier. If you're generally prone to panicking, then obviously things could get worse. Are you seeing more of this? And how should people first compose themselves before dashing off to buy medicines or block beds?

RK: I think having support systems, which we are good with in India, helps. Many of us stay in multigenerational families. We are a culture that comes together when people are sick. Before COVID, nobody went alone to a hospital, we always have relatives. So get that support system in place, even virtually over a phone. Make sure you have people to talk to, calm yourself by having the strategies in place because it is very hard. No one's denying that--especially if you're going into isolation, or another family member is. And you're getting horrible news from the [news] channels or 'WhatsApp University' telling you that oxygen is over. It's a huge thing to say calm, it is, but let's make that our goal whatever it takes. We also need to come together as small communities, have your resident welfare associations set up volunteers who can call people who are alone. Or [communicate that] hey, you can get this medicine here or these labs are still open and can come home or let me arrange this for you.

Finally, what should one do to avoid COVID-19?

AC: Get vaccinated as early as possible as per the government regulation. We hope and pray you don't get COVID-19 but even if you do, don't panic, the mortality is low--less than 1-2%. When you recover, please continue to use a mask, wash hands and keep a safe distance.

RK: I differ a little. If you do get the symptoms that I mentioned earlier, act as if it's COVID--isolate, get in touch with a doctor if you can. Get tested and don't panic. Most people do fine. To add to the vaccine bit, I have seen that among people who have [had] the vaccine, all have stayed home, no one had to be sent to the hospital. And these are senior citizens.

One more suggestion: If you're going to get the vaccine, make sure you wear an N95 mask. I cannot tell you how many people have come back after their vaccination and got the illness. So I'm pretty sure that they've got it at the [vaccination] centre by being in a closed place for that half hour or whatever, and not wearing a proper mask. So, it has to be an N95 mask if you are going for your vaccination.

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@indiaspend.org. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.