Dalits Are Still Converting To Buddhism, But At A Dwindling Rate

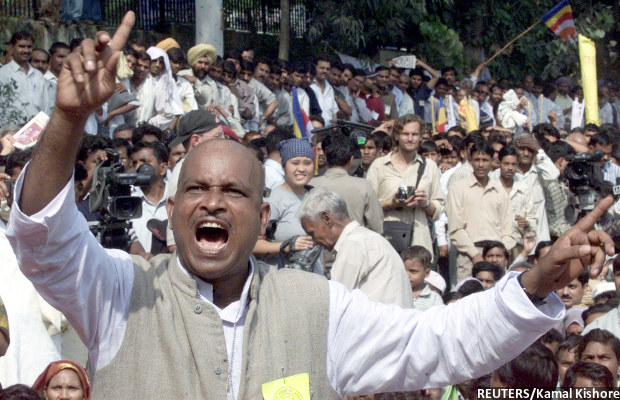

A Dalit or lower caste "untouchable" shouts anti-government slogans during a gathering of in New Delhi, November 4, 2001. Thousands of Dalits embraced Buddhism during the huge mass conversion ceremony in the heart of the city.

- Around 180 Dalit families converted to Buddhism after caste violence in Saharanpur district of Uttar Pradesh (UP) in May 2017.

- Bhim Army, the new group that seeks to give Dalit politics a more aggressive face, says it is considering a mass campaign for conversions to Buddhism.

- Last year, over 300 Dalits converted to Buddhism in Gujarat after seven of their caste were flogged for skinning a dead cow.

Dalits, ranked lowest on the Hindu caste hierarchy, first started converting to Buddhism as a political gesture in 1956. This was the year BR Ambedkar, a Dalit icon, embraced Buddhism contending that this was the only way to escape caste oppression.

The community has continued to use initiation into Buddhism as a gesture of protest. Every time the Dalit movement peaked, the number of conversions rose. After 1956, the number of neo-Buddhists--or fresh converts to Buddhism--grew again in the 1980s and 1990s because of the rise of the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP), a major Dalit-centric political party.

Today, around 87% of Buddhists in India are neo-converts; the rest belong to traditional Buddhist communities, mostly in the north-east of India and other Himalayan regions.

However, there has been a decline in the growth rate of Buddhists in India in recent years. Among religious groups, this decline is second only to the fall in the growth of Jains, according to Census data.

The number of Buddhists grew by 6.13% in 2001-11 and Hindus, 16.76%, Census data show. But in the previous decade, this trend had been the reverse: Buddhists (24.53%) and Hindus (20.35%).

Source: Census of India data here, here and here

This decline was most noticeable in states such as Karnataka, UP and Madhya Pradesh--known for their neo-Buddhist movements.

Maharashtra, which accounts for 77% of all Buddhists in the country, has also seen the growth rate in the community sliding from 15.83% in 1991-2001 to 11.85% in 2001-11.

Source: Census of India data here, here and here

What could be the reason for this slowdown? It could be because conversion is primarily used as a political tool by Dalits and this means fluctuations in numbers depending on factors that affect the community.

“This explains why many still follow Hindu rituals. However, there is a strong interest in learning more about the spiritual and religious aspects of Buddhism,” wrote Meena Srinivasan, a practising Buddhist and school teacher in this article.

New converts to Buddhism are returning to Hinduism or reporting themselves as Hindus in government surveys. Both these scenarios underscore the complexities that mark the neo-Buddhist movement in India.

Karnataka registered 75% decline in number of Buddhists

Maharashtra, which has around 90% of India’s neo-Buddhists, saw their numbers grow by 11.85% between 2001 and 2011, from 5.8 million to 6.5 million.

“The consistent influence of social reformers, including Jyotiba Phule and Dr Ambedkar, has ensured that people here are more aware and secure enough to leave their Hindu identity,” said Sandeep Upre, the president of Satyashodhak OBC Parishad, an organisation that conducts deeksha (initiation rites) programmes in Maharashtra.

Karnataka, on the other hand, registered a decline of 75% even in the total number of Buddhists between 2001 and 2011. This was a sharp reversal from the upsurge of 439% the state saw in 1991-2001. The earlier growth was in response to a strong political movement in 1990s which saw the BSP winning its first assembly seat in south India.

“The sway of the BSP has dissipated over the years which explains the decline to some extent. Another reason is the denial of caste certificates to neo-Buddhists by the state government. This excludes them from reservations in education and jobs,” said Mavalli Shankar, the state secretary of Dalit Sangharsh Samiti, an activist organisation based in Bangalore.

In 1990, an amendment was made in the Government of India (Scheduled Castes) Order of 1936 bringing neo-Buddhists into the category of Scheduled Castes. However, Karnataka has not issued an official order reflecting the change.

“It was all fine till the certificates were issued manually as issuing authority could make the changes by hand. But with introduction of computer-generated certificates, it’s not possible to alter the options programmed into the system,” said Devendra Hegde of Dalit Sanghatana Vedika, another activist organisation in Karnataka. To maintain the reservation advantage, some converts still maintain their Hindu caste certificate and report themselves as Hindus in government surveys while practising Buddhism.

Enumeration in Census may not be accurate, said Shiv Shankar Das, a former researcher with the Centre for Political Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, who studied the neo-Buddhist movement in UP. “Often the surveyor doesn’t even ask about religion once he hears a Hindu-sounding name. In other cases, recent converts may not be as assertive with their changed identity,” he added.

In UP, along with BSP’s fortunes, neo-convert numbers too decline--by 29.64%

Buddh Purnima and Vijayadashmi--the day Ambedkar embraced Buddhism--are special days for Dalits and neo-converts. Despite being a Hindu festival, Vijayadashmi is the day when King Ashoka, the biggest royal patron of Buddhism in history, took deeksha in 263 BCE.

Hindu right groups don’t see Dalit conversions to Buddhism as a challenge. This is because they see Buddhism as an offshoot of Hinduism and Buddha as an avatar (reincarnation) of Vishnu. But the repercussions of this assumption are bigger than those acknowledged.

Dalits in Saharanpur, hit by caste violence in May 2017, have complained that Hindu outfits treated them as their own until the assembly elections which saw the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) come to power in UP.

“The BJP, RSS (Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh) and Bajrang Dal are always seeking support based on the Hindu identity. When people reject Hinduism by embracing Buddhism, they also refuse to be part of their socio-political ambitions,” said Nawab Satpal Tanwar, a leader of Bhim Army, which has been accused by the UP police of inciting violence in Saharanpur.

The BJP had acknowledged the risk when it sponsored a six-month state-wide ‘yatra’ by 40 monks before the assembly elections to woo new converts to Buddhism.

UP has the largest number of neo-Buddhists after Maharashtra and West Bengal. The state not only has important Buddhist pilgrimage spots such as Sarnath and Kushinagar, but it also has considerable support for BSP.

During her term (2007-12) as chief minister of UP, BSP president Mayawati got several memorials and parks constructed besides districts and cities renamed after Dalit icons and Gautam Buddha. (She herself delayed embracing Buddhism to remain politically relevant for non-Dalits.)

In UP too, the population of new converts to Buddhism declined by 29.64% between 2001 and 2011.

Source: Centre for Policy Studies

There are differences between Ambedkarites on how to take the movement further. Bhim Army and its president, Chandrashekhar, take great pride in reinforcing their caste identity. “Dr Ambedkar’s message was annihilation of the caste, not its celebration. Such political associations with caste weaken the neo-Buddhist movement instead of strengthening it,” said Das.

Das pointed out that UP has not been able to achieve what Maharashtra has in terms of assertiveness. “There was en masse conversion in 1956 and hence the state had a good strength of neo-Buddhists from the very beginning. They don’t look up to any political party because they are themselves a force,” he adds.

Ambedkar’s dhamma journey

Ambedkar’s interest in Buddhism went back to 1908, when he first read about Buddha’s life and reached its zenith in 1935 when he declared, ‘Although I have been born a Hindu, I will not die a Hindu.’ His essay, The Annihilation of Caste, stated that the greatest barrier to the advancement of the untouchables was Hinduism itself.

Ambedkar also identified Buddhism and Sikhism as the two home-grown religions that defied Brahmanism. “You must take the stand which Guru Nanak took. You must not only discard the Shastras, you must deny their authority, as did Buddha and Nanak. You must have courage to tell the Hindus that what is wrong with them is their religion--the religion which has produced in them this notion of the sacredness of Caste,” he wrote.

His stance was seen as a response to Gandhi’s who stressed the removal of untouchability, not caste system itself.

‘Conversion is a rejection of caste discrimination’

On a small hill overlooking Dhank village in Rajkot district of Gujarat, there’s a small Shiva temple. Around 25 residents of the village, however, don’t enter this temple. They also refuse to attend any religious festivals here.

Bharatbhai embraced Buddhism after reading the Gujarati translation of Ambedkar’s The Buddha and his Dhamma. He also initiated eight other families of the village into the religion five years ago.

“I realised that Buddhism is the only religion that truly stresses on humanity. It does not differentiate between people. Taking deeksha thus came naturally and also as response to those who don’t consider us their equals,” Bharatbhai says.

But does conversion change how Dalits are treated by casteist elements? “If neighbours continue to treat us according to our caste, it’s their ignorance. We cease to be a Hindu and that act is a redemption enough for us,” said Upre.

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@indiaspend.org. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.

__________________________________________________________________

“Liked this story? Indiaspend.org is a non-profit, and we depend on readers like you to drive our public-interest journalism efforts. Donate Rs 500; Rs 1,000, Rs 2,000.”