Despite Law, 70% Working Women Do Not Report Workplace Sexual Harassment; Employers Show Poor Compliance

"Three years ago, I was working as a fellow at a non-profit organisation based in New Delhi. At one point, I felt the need to flag the management about some coordination issues I was facing with my superior. I took my problems to another programme manager. But he started making unwanted overtures the moment I walked into his office.

“He suggested that we go to Connaught Place for a chat. I agreed but then he later insisted that I accompany him to his place. Although I resisted, he persuaded me to agree. On the way, he started touching me inappropriately and commented on what I was wearing. When we reached his place, he asked me if I drink and when I said no, he asked me to sleep with him. Despite a clear ‘no’, he continued to force himself on me.

"My colleagues encouraged me to file a complaint. I found that although my contract mentioned a committee to investigate sexual harassment, there were no details. There was mention only of a panel that would be constituted in ‘rare instances of sexual harassment’.

“I took up the complaint with my superior, who then took it to the human resources (HR) manager and the city director. But my relationship with my boss was already strained -- he said it was all my fault. I ended up leaving my fellowship incomplete. Before I left, the HR manager sought a written exit interview and even though I mentioned the harassment my complaint was not taken up. The programme manager’s career, however, soared high.”

Ridhima Chopra, 25, is among the growing number of Indian women encouraged to complain about harassment at work by the Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act, 2013, promulgated in the wake of the 2012 Delhi gangrape. Yet, 70% women said they did not report sexual harassment by superiors because they feared the repercussions, according to a survey conducted by the Indian Bar Association in 2017 of 6,047 respondents.

An IndiaSpend analysis of available data and conversations with working women showed there was an increase in reported cases of harassment--to 2015, the year for which latest data are available.

Between 2014 and 2015, cases of sexual harassment within office premises more than doubled--from 57 to 119--according to National Crime Records Bureau data. There has also been a 51% rise in sexual harassment cases at other places related to work--from 469 in 2014 to 714 in 2015.

Source: Crime in India 2014 and 2015, National Crime Records Bureau

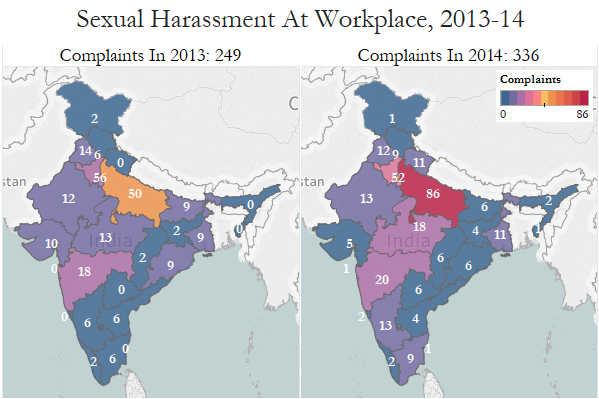

In the year before, between 2013 and 2014, the National Commission for Women reported a 35% increase in complaints from 249 to 336, according to this December 2014 reply filed in the Lok Sabha (the lower house of Parliament).

Source: Lok Sabha

Despite the rise in numbers, women, like Chopra, are finding that their complaints are not redressed effectively by employers. Employers are either unaware of the law’s provisions or have implemented them partially and even those that do set up internal panels have poorly trained members.

Above all, there is little gender parity in organisations even today. The high profile case of the woman employee at The Energy & Resources Institute who had to fight a case of harassment against the company’s former director general, RK Pachauri, for two years despite clear evidence illustrates this inequity.

As will become clear in later sections, these problems apply not just to private and public sector establishments but also to relatively younger information technology (IT) companies.

Why Riddhima failed to get justice: Redressal system is still flawed

An internal complaints committee (ICC) is mandatory in every private or public organisation that has 10 or more employees, according to the Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act, 2013. However, 36% of Indian companies and 25% of multinational companies had not yet constituted their ICCs, the 2015 research study, Fostering Safe Workplaces, by the Federation of Indian Chamber of Commerce and Industry (FICCI) showed. About 50% of the more than 120 companies that participated in the study admitted that their ICC members were not legally trained.

Kunjila Mascillamani, a freelance writer, had filed a complaint against sexual harassment while she was a student at the Satyajit Ray Film and Television Institute (SRFTI) in Kolkata. “In 2015, I went to the dean of my school to register a sexual harassment complaint. He said the institute has no mechanism to deal with such matters. I didn’t know the provisions of the law on workplace harassment and went to the director to tell him that we needed a mechanism to address such issues. He pointed out to me that an internal committee against sexual harassment for women already existed at the institute. I was shocked to find that the dean had lied to me,” she said.

Mascillamani had filed two cases--one of harassment and another of rape. The verdict on harassment was passed in July 2016 and the professors who harassed her were asked to take retirement. The rape case is still pending in court.

SRFTI chairperson Partha Ghose in an interview said that the complaints of sexual harassment were a “new and shocking” experience for him. He described it as a “disciplinary problem” on which the institution had acted as required by the law.

Private problem: 40% of IT and 50% of ad and media companies oblivious to law

All ministries and departments in the government of India have constituted ICCs, the ministry of women and child development told the Lok Sabha in this December 2016 reply. The ministry of corporate affairs--along with industry bodies ASSOCHAM, FICCI, Confederation of Indian Industry, Chamber of Commerce & Industry, and National Association of Software and Services Companies--was requested to ensure its effective execution in the private sector.

The law imposes a penalty of upto Rs 50,000 on employers who do not implement the Act in the workplace or even fail to constitute an ICC. But, the number of employers who do not fully comply with the law indicates that there is little monitoring of their redressal machinery.

There is a high rate of non-compliance in the private sector, as is evident in the 2015 study, Reining in Sexual harassment at Workplace, by Ernst and Young. Two in five IT companies were oblivious to the need to set up ICCs and 50% of advertising and media companies had not conducted training for ICC members, the study found.

Three years ago, Meera Kaushik (not her real name) had started working in a Pune-based media and advertising company as a copywriter. She had an uneasy time during her job interview when her future employer insisted that she smile. “One day, when I was at work and feeling restless, my boss demanded to know why I was upset. He forced me to smile and leave my hair open. I didn’t realize that this was harassment. Such expressions of concern are often considered a part of the work culture. I didn’t object because I feared losing my job,” she said.

Kaushik finally did leave her job.

Why women fail to report workplace harassment

Anagha Sarpotdar, a researcher who works on sexual harassment at workplace and an external member appointed to monitor such trials by Mumbai city, was of the view that employers are wrong to discourage reporting in order to protect their image.

“Low or no reporting speaks volumes about the gender sensitivity of a particular organisation,” she said. “Further, women may not know where to go to report harassment or it could be that the cases may not have been dealt with sincerely. Often, women go to committees believing them to be independent and find that they are actually puppets in the hands of their superiors.”

Chopra pointed out that though her contract promised “strict action” against sexual harassment, there was little awareness about the issue at her former workplace. And no effort was made to create awareness either.

“Under the law, there are guidelines to display information at a conspicuous place in the workplace, list the penal consequences of sexual harassments. There is also an order directing the ICC to create awareness regarding sexual harassment in all government departments and ministries. But these don’t exist,” said Shikha Chhibber, a Delhi-based lawyer.

During the hearings on her case, the freelance writer Mascillamani said she was blamed for the incident. “All the faculty members and the administration had turned against me and I was slut-shamed on social media. It was at this juncture that I approached an NGO to appoint an external member to oversee the procedure and ensure a fair trial,” she said.

As Sarpotdar pointed out, for many organisations, training sessions on workplace harassment is only a box to be ticked. “They lack the perspective on gender equality to put the law into action,” she said.

(Chachra is an MPhil student at Delhi’s Jawaharlal Nehru University. She has previously worked at Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative.)

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@indiaspend.org. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.

__________________________________________________________________

“Liked this story? Indiaspend.org is a non-profit, and we depend on readers like you to drive our public-interest journalism efforts. Donate Rs 500; Rs 1,000, Rs 2,000.”