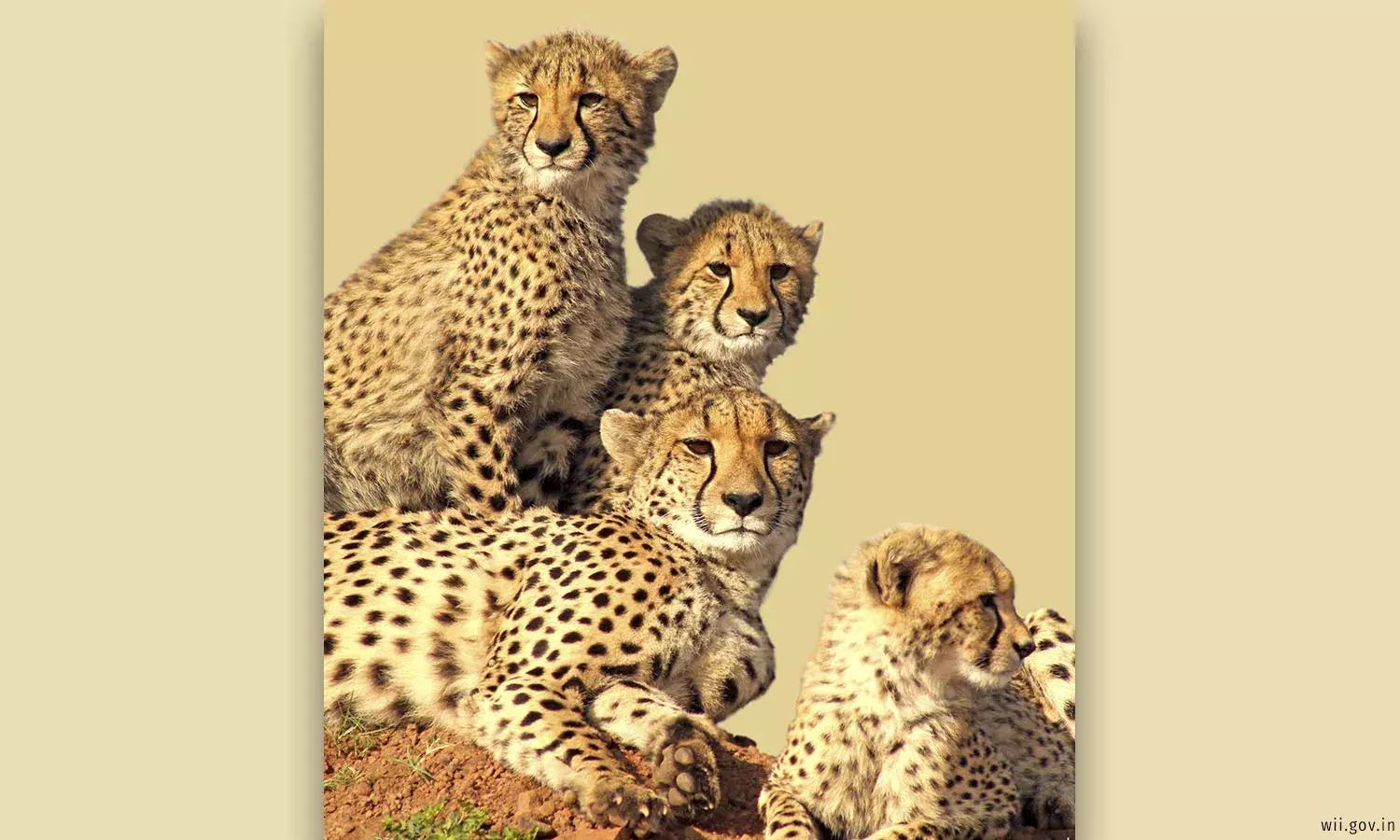

Deaths, ‘Runaways’, Space Crunch: Is India’s Cheetah Project On The Right Track?

India’s Kuno National Park was to accommodate 21 cheetahs but its management now says Kuno can house only around 10 of the 20 cheetahs translocated to India

Mumbai: Less than a year since 20 African cheetahs were translocated to India, three adults and three cubs have died, Madhya Pradesh’s Kuno National Park (KNP) officials have written to the Union government asking for relocation of some cheetahs to other parks, and experts have questioned the long-term viability of the project.

KNP now has 17 adult cheetahs, and one cheetah cub. International consultants now suggest placing some cheetahs under ‘fenced reserves’ as against the Indian government’s original intention to establish “a free ranging population”.

After the death of three adults and three cubs, the government formed a steering committee to guide the project, and announced that government officials will be visiting African countries for studying the cheetah. The Supreme Court had, when it allowed cheetah introduction in 2020, already formed an expert committee to supervise the process.

The government’s criteria for the project’s success for the short term, according to the Cheetah Action Plan released in 2021, includes a 50% survival rate (10 of 20 cheetahs) for the first year; cheetahs establishing home ranges in KNP; survival of wild-born cheetah cubs for more than a year, and F1 generation--that is, the first offsprings--breeding successfully.

The project completes one year on September 17, 2023. Even though less than 50% of cheetahs have died and the deaths were not unexpected, all of the adult cheetahs are yet to establish home ranges at KNP.

The long term success of the programme includes establishing a long-term viable metapopulation in India, either in KNP or in a combination of three-five cheetah reserves. The project will be a failure if the introduced cheetahs do not survive, or fail to reproduce in the wild in five years, among other things. “In such a case, the Program needs to be reviewed for alternative strategies or discontinuation,” the action plan recommends.

Speaking about the cheetah deaths and the project so far, Union Environment Minister Bhupender Yadav on June 1 reportedly said, "we take responsibility for whatever happened", but asserted that the translocation project will be a major success.

IndiaSpend reached out to the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MOEF) and the National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA) with detailed queries on the cheetah project, Kuno’s cheetah carrying capacity, whether cheetahs will be moved out of Kuno, whether India will consider fenced reserves, among other questions. This story will be updated when they respond.

IndiaSpend takes a look at the current status of the project and what international and national experts say about its future.

Four births, six deaths

The last cheetahs in the wild in India were recorded in 1948, when three cheetahs were shot in the Sal forests of Koriya District, Chhattisgarh. There were a few sporadic reports of sightings from the central and Deccan regions till the mid-1970s. Currently, the subspecies found in Iran is the same as the one that disappeared from India in the 1940s, and were officially declared extinct in 1952.

The cheetah is listed as ‘vulnerable’ in the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species of 2021, with only 6,517 mature individuals left in the world.

As fewer than 50 mature cheetahs remain in Iran now, this species could not be translocated to India, and the Indian government decided to undertake the transcontinental translocation of the African cheetah to India instead.

On September 17, 2022, India welcomed eight cheetahs from Namibia and in February 2023 it welcomed 12 more cheetahs from South Africa. They were quarantined in KNP’s enclosures and over time, a few were released in the wild. At the time of writing this story, there were seven cheetahs in the wild, while 10 remain in quarantine.

In March 2023, the female cheetah ‘Jwala’ birthed four cubs. However, on May 23, a press note stated that one of the cubs, the weakest of the lot, had died. Its death must be “looked in the context of survival of the fittest”, the press release said. The government later confirmed that two more cheetah cubs also died the same day and attributed the deaths to heat, weakness and dehydration. The fourth cub was under critical care, but is stable and in quarantine at KNP, an official at KNP told IndiaSpend.

The government says that the survival rate of cheetah cubs in the wild is extremely low, around 10%.

In March, the cheetah named ‘Sasha’ died from chronic renal failure. In April, another cheetah named ‘Uday’ died due to terminal cardio-pulmonary failure.

In May, the female cheetah named ‘Daksha’ died due to violent interactions with the male cats during a courtship or mating attempt. The government had maintained that such violent behaviours by male coalition cheetahs towards female cheetahs during mating are common and that the chances of intervention by the monitoring team were almost non-existent and practically impossible.

South African wildlife expert Vincent van der Merwe, manager of the Cheetah Metapopulation Project, who is advising the Indian government on the cheetah project reportedly said that though cheetah deaths have been within the acceptable range, the team of experts that reviewed the project did not expect males to kill a South African female cheetah during courtship and that these experts take “full responsibility".

On May 25, Van der Merwe cautioned that more cheetahs will die in the next few months as they try to establish territories and come face to face with leopards and tigers in KNP.

"There has never been a successful reintroduction into an unfenced reserve in recorded history. It has been attempted 15 times in South Africa and it failed every time. We are not advocating that India must fence all of its cheetah reserves, we are saying that just fence two or three and create source reserves to top up sink reserves," Van der Merwe told the Press Trust of India.

India’s forests and protected areas have always been unfenced whereas in some countries, such as Australia and many African countries, some reserves are fenced.

However, the chairman of the cheetah steering committee Rajesh Gopal reportedly told PTI on May 31 that India will not fence its cheetah habitats as that goes against the basic tenets of wildlife conservation.

Unusually long quarantines

Some cheetahs have seen an unusually long quarantine period even as the action plan had expected to release them after one month (males first and females around a month after the males).

“To only focus on births and deaths is missing the fundamental question: Is India fully prepared to host free-ranging, wild cheetahs?” asks wildlife biologist and conservation scientist Ravi Chellam. “Why are many of the cheetahs in prolonged captivity even when the action plan said they will be released in a couple of months? What was the need to allow the cheetahs to mate in captivity?”

The plan is to translocate a further 12 cheetahs annually for the next eight to 10 years, according to the Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) signed with South Africa.

In the context of Uday’s death, a South African cheetah, Van Der Merwe reportedly said, “He [Uday] was very healthy before shifting to Boma in July 2022 [enclosure in SA] for the translocation project. After 10 months in captivity, he lost fitness and suffered from chronic stress,” Merwe said, adding that the animals must be released in the wild. “The cheetahs must go back into the wild where they belong. They are unhappy in cages.”

In May, the government announced that five cheetahs will be released in the wild before the monsoon, while the rest will continue to stay in the enclosures until a review after the monsoon.

After its first meeting on May 31, the steering committee has reportedly announced that it will be releasing seven more cheetahs in the wild in Kuno by the third week of June.

Kuno National Park might be too small for the cheetahs

The management of KNP, in April 2023, wrote to the Union government to relocate some cheetahs out of KNP, as they lack the manpower and infrastructure to support the felines in the wild, the Indian Express reported in May 2023. The Supreme Court recently asked the Central government to not allow politics to interfere with the movement of some cheetahs to Mukundara Tiger Reserve in Rajasthan just because ‘Rajasthan is an opposition-ruled state’.

J.S. Chauhan, Principal Chief Conservator of Forests for Madhya Pradesh, confirmed to IndiaSpend that he had indeed written to the NTCA to find a new home for the cheetahs.

The Cheetah Action Plan says that KNP can sustain up to 21 cheetahs currently and based on carrying capacity estimates, the potential cheetah habitat covering over 3,200 sq km in the larger Kuno landscape could provide a prey base for up to 36 cheetahs. Experts had questioned this estimate even before the cheetahs were introduced last year, we reported in September 2022.

While the Union government has maintained that KNP has a sufficient prey base, KNP is being restocked with prey, Chauhan said. He explained that there was no shortage of prey at the park but this was being done for a genetic diversity of prey.

And now, Kuno’s capacity needs to be reviewed, according to its own management.

In April, the Madhya Pradesh government asked the NTCA, which is implementing the cheetah project, to find a new habitat in the wild for some of the cheetahs brought to Kuno as they would not be able to monitor the movements of all of them living free. An official reportedly said that Kuno can accommodate only nine to 10 cheetahs as a cheetah’s territory is spread over 300 to 800 sq km. This falls far short of what the Cheetah Action Plan had estimated in 2021.

“My job is to say what should be done, what is the correct step technically. Taking a decision on that is the Centre’s prerogative,” Chauhan of KNP said. “If you can apply common sense, the current situation is like having all your eggs in one basket. If something happens like a virus or disease breakout [among the cheetahs], then the entire population is at risk. It is always advisable to have two metapopulations in two places, it works as an insurance also.”

He also pointed out that the action plan had expected up to 50% mortality.

One indicator of KNP falling short of space might be the fact that one of the first cheetahs to be released in the wild had ‘strayed’ away from KNP and had to be ‘retrieved’. Officials have stated that henceforth such cheetahs will be recaptured only if they are in danger.

In April 2023, a team of independent scientists from South Africa released a paper which questioned India’s cheetah introduction project. They questioned Kuno’s prey-base calculations and stated that the viability analysis, risk assessment and data on which these are based are not available for scientific scrutiny.

“As such, it is impossible to evaluate what risks were identified and how they were mitigated against. This is particularly important in this scenario in which the animals are likely to come into contact with novel pathogens, unknown and unpredictable ecological interactions (such as predator–prey), a high poaching threat and undefined conflict with humans,” the researchers stated.

“It appears that the welfare of the animals is being compromised through a lack of mitigation of threats to their post-release survival and inadequate fencing, and the conservation potential of the animals is being squandered.” It added that the funds India has used for the cheetah project might be better suited for conservation of some Indian species.

Another set of Indian and international researchers called the Action Plan ‘ecologically unsound’, in a 2022 paper. This paper relied on a study of a free-ranging cheetah population in the prey-rich Maasai Mara landscape in Kenya which found that cheetahs are characterised by disproportionately large home range sizes (over 750 sq km) and very low population densities (about one cheetah per 100 sq km). Kuno is spread over 748 sq km.

“The derived carrying capacity of about 3 cheetahs per 100 sq km for Kuno was based on an out-of-date density estimate from Namibia, where the study area size was far lower than the home range size…Therefore, we anticipate that neither Kuno National Park, unfenced, harbouring about 500 feral cattle and surrounded by a forested landscape with 169 human settlements, nor the other landscapes considered are of the size and quality to permit self-sustaining and genetically viable cheetah populations,” they stated.

However, consultants and other experts working with the Indian government disagreed.

“Historical cheetah population densities in East Africa were likely to have been higher before marked declines in their prey base and cheetahs are likely to have been more abundant in more productive areas of their historical range that have now been taken over by livestock farming. In a reserve in southern Botswana, with fences that are permeable to predators, a mean true density of 5.23 cheetahs per 100 sq km has been reported, indicating that higher densities are possible,” they wrote in an article, published in Nature Ecology and Evolution in February 2023.

Researchers from Germany predicted in April 2023 that irrespective of the territory size, the three males from Namibia will occupy the entire KNP, thus not leaving space for additional territories for males introduced from South Africa. The researchers also said that the eight Namibian cheetahs “will conduct extensive excursions outside the KNP during their exploration phase, potentially coming into conflict with livestock farmers”. They also predicted that additional males brought in or born in KNP will settle at a distance of 20–23 km away from the first two established territories, coming into conflict with livestock farmers.

On May 8, the Indian government said that it is impossible to determine the precise cheetah carrying capacity in KNP until the cheetahs have properly established their home ranges and secondly, the home ranges of cheetahs can overlap substantially depending on the prey density and several other factors.

“While many have made predictions about the anticipated carrying capacity of cheetahs in KNP based on other ecosystems in Namibia and East Africa, the actual number of animals that the reserve can accommodate can only be assessed after the animals are released and have established home ranges. Cheetah home-range sizes and population densities vary tremendously for different cheetah populations in Africa and for obvious reasons, we do not have useful spatial ecology data for cheetahs in India yet,” the statement said.

Chellam, CEO of Metastring Foundation, Coordinator of Biodiversity Collaborative and also one of the authors of the paper which called the Action Plan ‘ecologically unsound’, says that KNP cannot hold more than 8-10 cheetahs in total, and thus additional sites should have been explored and prepared at least three years ago. “And if no attempt to introduce cheetahs in unfenced reserves has succeeded in history, then why are we doing it in India? It is a well established fact that India’s protected areas are not fenced.”

Wildlife Institute of India (WII) scientist Qamar Qureshi, who is also part of the steering committee, had said in April that releasing all cheetahs in the wild in KNP was never the plan.

“We know that Kuno does not have enough space for all cheetahs and that is why Nauradehi Wildlife Sanctuary, Mukundra Wildlife Sanctuary, and Gandhisagar Wildlife Sanctuary were selected as other possible homes for them,” he had said. Qureshi had added that Mukundara, in Rajasthan, is ready for the cheetahs and the Union environment ministry and NTCA will take the final decision.

However, the Centre had reportedly rejected the Rajasthan government’s request to shift cheetahs to Mukundara in 2022. The Gandhisagar sanctuary might take another year to be ready.

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@indiaspend.org. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.