Education, Economic Independence Can Reduce Suicides In Indian Women

New Delhi: If Indian women are educated, economically independent and faced lesser domestic violence than they do, the rate at which they kill themselves today--more than twice the global average rate--is likely to drop, according to experts.

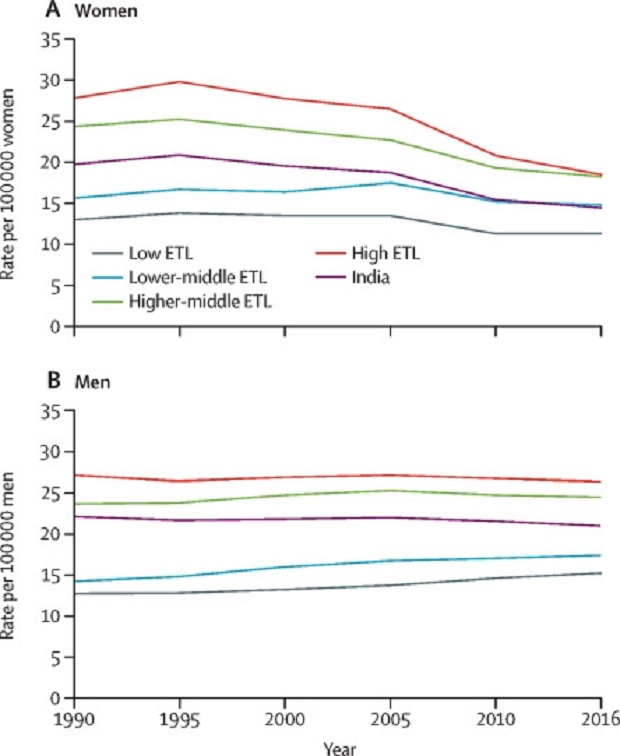

About 15 women committed suicide per 100,000 in India--2.1 times the global average and the sixth highest the world in 2016, according to the Gender Differentials and State Variations In Suicide Deaths in India: The Global Burden of Disease Study 1990–2016 study published in The Lancet, a medical journal, in September 2018.

There has been a 27% decline in Indian women’s age standardised suicide death rate (SDR) while the age standardised SDR did not change in men from 1990 to 2016. Age standardised rates help compare prevalence among different populations.

“This may be because of increasing education levels, higher age of marriage in women and economic progress between 1990 and 2016,” said Rakhi Dandona, lead author of the paper and professor of public health at the Public Health Foundation of India, a think tank and advocacy.

Married women account for the highest proportion of suicide deaths among women in India, noted the study, despite the fact that marriage is known as a protective factor against suicides globally. This can be explained by factors such as arranged marriage, early marriage, young motherhood, low status, domestic violence and [lack of] economic independence, said the study.

Early marriage and low status

Early marriages are still common in India; 27% Indian girls were married before 18 years and 8% of girls (15- 19 years) were pregnant before the age of 19 years, according to the latest National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4).

Domestic violence has a direct relation with suicide ideation in women across the world. Almost 29% married women in the 15-49 years age group in India have experienced spousal violence and 3% faced violence during pregnancy, NFHS-4 showed.

Only 36% Indian women aged 15-49 years have more than 10 years of education. So, coupled with early marriage, motherhood and domestic violence, Indian women do not have the education or economic independence to fall back on.

“Unlike men, education is a protective factor for women against suicide,” said Lakshmi Vijayakumar, SNEHA India and Voluntary Health Services, Chennai, and one of the authors of the study.

While the most common reason for men to commit suicide is financial debt, it is family and marital problems for women, she said.

Preventing child marriages, educating girls and curbing dowry will help prevent suicides in women, Vijayakumar said.

Another important factor for suicides by women is alcohol consumption among men. “Many studies have shown a direct link between alcohol abuse by men, domestic violence and suicides by women,” she added.

Reduction of sexual and intimate partner violence can reduce suicides in women; according to an estimate, in the absence of sexual abuse, female suicide attempt over lifetime would fall by 28% relative to 7% in men.

Difference in men and women

“While women’s suicides may have decreased due to various social factors, it is worrying that men’s suicide rate has not changed in nearly three decades,” said Dandona.

Deaths due to suicide among women were 20 per 100,000 in 1990 and 15 per 100,000 in 2016; in men, the figure was 22 per 100,000 in 1990 and 21 per 100,000 in 2016.

Globally, the suicide risk in men is two times--200%--as high as women; in India, the difference is smaller: Only 50% higher than women.

Suicide was the leading cause of death in the 15-39 years age group, accounting for 71% deaths in women and 58% deaths in men.

Source: The Lancet

Note: ETL refers to epidemiological transition level--that is, transition from communicable to non-communicable diseases with development of the region. Low ETL refers to high burden of communicable diseases and high ETL refers to high burden of non-communicable diseases.

Women’s suicide attempts go unreported

While these estimates are significant in understanding the extent of suicides in India, they miss out on suicide attempts and suicides that do not lead to deaths.

Actual suicides of women are often not reported because families are held responsible if suicides occur within seven years of marriage. There was a 37% difference in estimated suicides in women versus suicides reported by the National Crime Records Bureau compared to 25% difference in estimated suicides and reported suicides in men, according to the estimates of the 2014 suicide mortality study.

Many suicide attempts by women by poisoning have been termed as accidental poisoning, said Sangeeta Rege, coordinator of CEHAT, a health advocacy that started the first hospital-based crisis centres for women facing violence in India.

At any given time, there are 25 women admitted in government hospitals per month under “accidental poisoning”, she said.

“We started the first Dilaasa [hospital-based crisis centre] in 2000 after meeting many such women who had ingested poison. In hospitals, these women received medical treatment but did not receive any support that could prevent future attempts at suicide.”

Psychiatrists tend to view women as having adjustment issues while ignoring the hostile environment she lives in that makes her take the extreme step, she added.

There has also been a rise in suicides in adolescent girls, according to the study. Nearly 17% deaths of girls aged 15-19 years were due to suicide, the third highest incidence among all age groups.

“Parental abuse is hardly ever spoken about but parents are extremely abusive and controlling; young girls have no autonomy or independence to make their own decisions,” said Rege.

As much as 30% of domestic violence was committed by parents or step-parents, according to the national health survey.

Regional differences

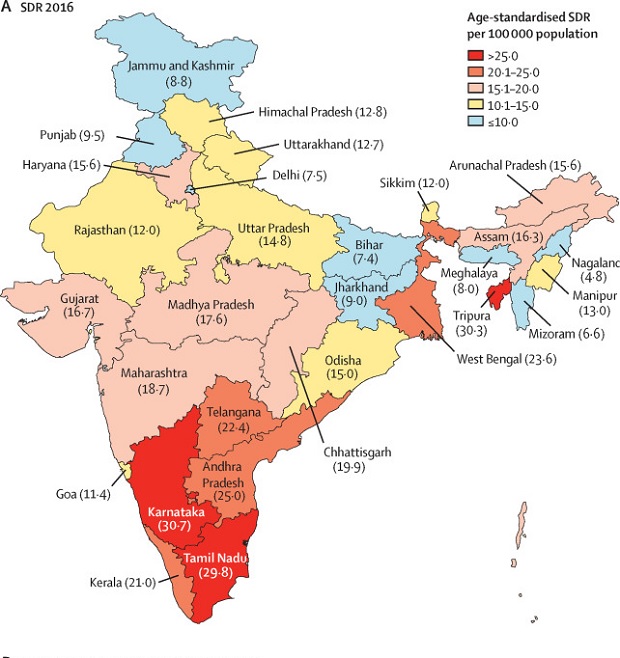

Suicide was the leading cause of death in 26 of 31 states for women aged 15-29 years. Suicide contributed to a lower proportion of deaths in less developed states than developing and developed states, said The Lancet study.

Source: The Lancet (Image 4, age standardised SDR in 2016)

The highest SDR was in Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, West Bengal, Tripura, Andhra Pradesh and Telangana--more than 18 per 100,0000 population; only three countries--Greenland (38.1), Lesotho (35.3) and Uganda (18.7)--have higher SDR.

The southern states of Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Karnataka and Tamil Nadu had higher SDR for men and women than other parts of the country.

“Suicide is very complex and cannot be reduced to a single factor,” said Dandona.

“Southern states are more urbanised, and that leads to stress factors like overcrowding, smaller families and expensive lifestyles leading to high SDR. With time, these stabilise and then there is increase in SDR in rural areas as more people move to cities and there is lack of development.”

The highest declines in suicides among women from 1990 to 2016 were in Uttarakhand (45%), Sikkim (43%), Himachal Pradesh (40%) and Nagaland (40%).

Need more research on suicides in India

Suicides are a leading cause of death among the young (15-39 years) but there is very little research on suicides, and how to prevent them other than public attention towards farmer suicides.

Unchanging rates of suicides in men need to be explored. “For suicides among men in India, it appears that young adults are a vulnerable group, and marriage does not seem to be protective for them either,” the Lancet study noted.

Men tend to internalise the stress and have trouble seeking help when facing emotional issues. “There are so many cases where there has been no sign of trouble till the man has taken his own life,” said Dandona.

Decriminalisation of suicides in 2017 as well as passing of the National Mental Health Act are expected to improve access to mental health treatment and reduction in stigma and under-reporting of suicide, said the study.

Restricting the use of pesticides, which was found to be the most common way to commit suicide, can help as would regulating the sale of alcohol. “Educating general physicians to detect signs of depression, loneliness and suicides can help and school level education to help resolve interpersonal conflicts and dealing with emotions like anger,” Vijayakumar said.

“We need to start first by declaring suicide a national health priority,” said Vikram Patel, professor, department of global health and population, Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health, and author of the 2014 study on suicides in India. He suggested setting up a cross-sectoral/ministerial commission to prioritise, implement and evaluate strategies for reducing suicides.

India must take inspiration from China and Sri Lanka where suicide rates have plummeted in the last decade to find out which interventions work, Patel added.

(Yadavar is a principal correspondent with IndiaSpend.)

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@indiaspend.org. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.