காலநிலை உச்சிமாநாட்டின் அவசர கூட்டத்திற்கு ஐ.நா தயாராகும் சூழலில் இந்தியாவுக்கான அவசரம் தெளிவாகிறது

மும்பை / நியூயார்க்: உலக காலநிலை மாற்றத்தின் - வேகமாக உருகும் ஆர்க்டிக்கில் இருந்து உருவாகும் சூப்பர் புயல்கள் கரீபியன் அல்லது மும்பையில் இருந்தாலும் சரி - அதிகரித்து வரும் இத்தகைய விளைவுகளை களைவதற்காக அழைக்கப்படும் காலநிலை உச்சி மாநாட்டின் அவசர கூட்டத்தில் பங்கேற்க, உலகத்தலைவர்கள், 2019 செப்டம்பர் 23இல் நியூயார்க் ஐக்கிய நாடுகள் சபை (ஐ.நா) தலைமையகத்தில் கூடி விவாதிக்க உள்ளனர்.

இந்த நிகழ்ச்சி நிரலில் முதன்மையானது, காலநிலை மாற்றத்திலிருந்து ஏற்படும் சேதத்தை கட்டுப்படுத்துவதற்கான வழிகள் பற்றிய விவாதங்கள் ஆகும். இது குறித்த தினசரி அறிக்கைகளை வழங்க, உச்சிமாநாடு ஏன் இந்தியாவுக்கு முக்கியமானது என்பதை உங்களுக்குத் தெரிவிக்க, இந்தியா ஸ்பெண்ட் குழு அங்கு இருக்கும். பிரதமர் நரேந்திர மோடி, செப்டம்பர் 27, 2019 அன்று உச்சி மாநாட்டில் உரை நிகழ்த்த உள்ளார்.

ஐ.நா பொதுச்செயலாளர் அன்டோனியோ குடெரெஸ் ஏற்பாடு செய்துள்ள இந்த உச்சி மாநாட்டில் தமது காலநிலை தொடர்பான உணர்ச்சிபூர்வ முறையீடுகளால் உலகத்தின் கவனத்தை ஈர்த்த ஸ்வீடனைச் சேர்ந்த 16 வயது கிரெட்டா துன்பெர்க் உட்பட சமூக அமைப்புகள் மற்றும் காலநிலை ஆர்வலர்கள் பங்கேற்கின்றனர்.

குளிர்கால வெப்பநிலை 1990ஐ விட ஆர்க்டிக்கில் ஏற்கனவே 3 டிகிரி செல்சியஸ் அதிகமாக இருப்பதால், காலநிலை மாற்றம் முக்கியமானதாகவும் அவசரமாகவும் மாறிவிட்டது என்று நிபுணர்கள் தெரிவித்தனர். கடந்த 1850 ஆம் ஆண்டில் முறையான பதிவு பராமரிக்க தொடங்கியதில் இருந்து சராசரி உலகளாவிய வெப்பநிலை ஏற்கனவே 1 டிகிரி செல்சியஸ் அதிகமாக உள்ளது என, காலநிலை மாற்றம் குறித்த அறிவியலை மதிப்பிடுவதற்காக உருவாக்கப்பட்ட ஐ.நா. அமைப்பான, காலநிலை மாற்றம் தொடர்பான சர்வதேச அரசு குழு - ஐபிசிசி (IPCC) அக்டோபர் 2018 அறிக்கை தெரிவிக்கிறது.

உலக வங்கியின் மதிப்பீடுகளின்படி, இந்தோ-கங்கை சமவெளியில் வாழும் 60 கோடி மக்கள் பாதிக்கப்படுகின்றனர்; ஏனெனில் புவி வெப்பமடைதல், இமயமலை பனிப்பாறைகள் உருகுவதற்கு காரணமாகிறது. இது கங்கை மற்றும் அதன் துணை நதிகளின் நிலையான நீரோட்டத்திற்கு அச்சுறுத்துகிறது.

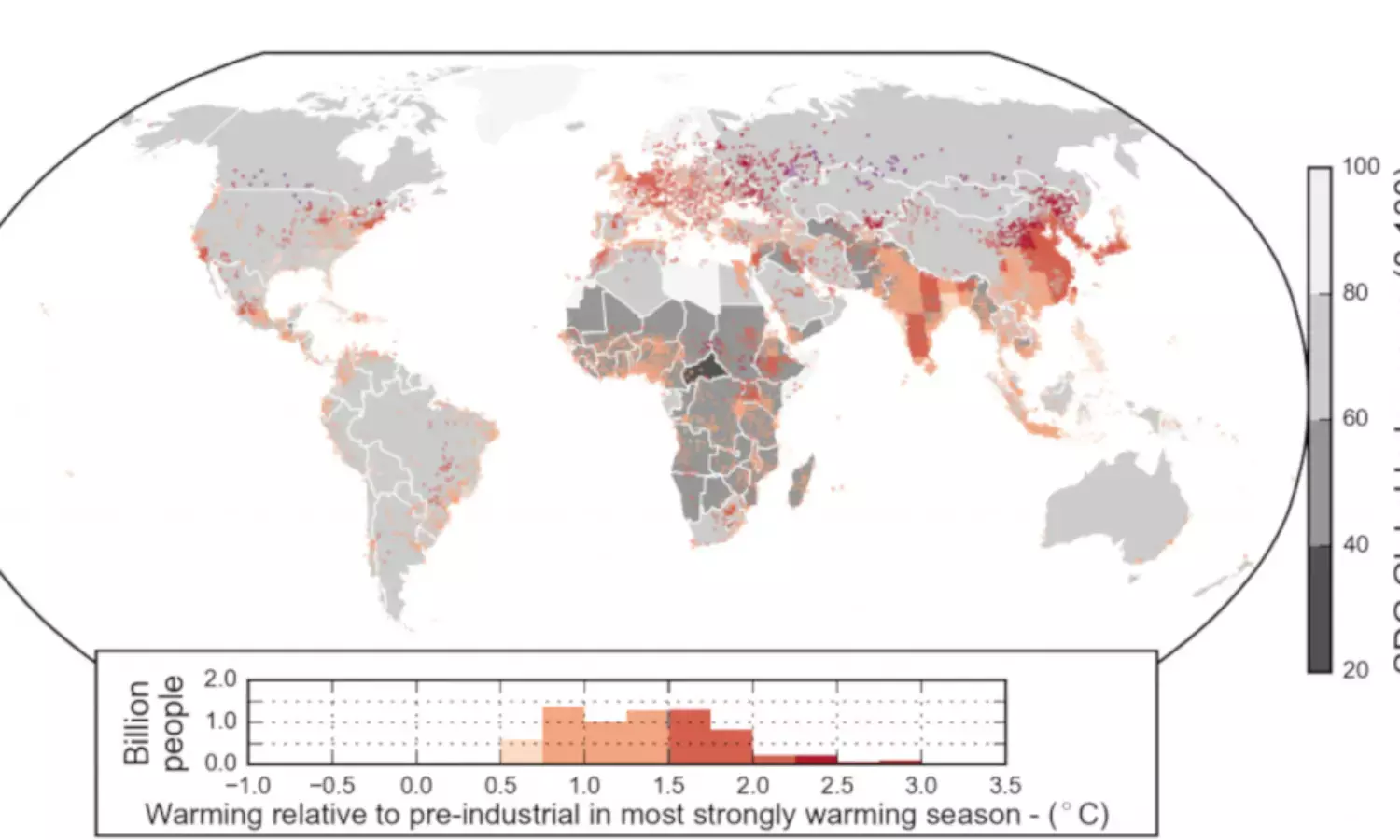

ஏறக்குறைய 14.8 கோடி இந்தியர்கள் காலநிலை மாற்றத்தின் "கடுமையான வெப்பப்பகுதிகள்" நிலவும் இடங்களில் வாழ்கின்றனர், ஏற்கனவே பெரிய அளவிலான மாற்றங்களை சந்தித்து வருகின்றனர் என்று, இந்தியா ஸ்பெண்ட் அறிக்கை திட்டத்தில் தெரிய வந்ததுள்ளது. காலநிலை மாற்றம் வெள்ளம் மற்றும் அனல் காற்று போன்ற தீவிர நிகழ்வுகளின் அதிகரிப்புக்கு வழிவகுக்கிறது. இது இந்தியாவின் தண்ணீர் பாதுகாப்பை அச்சுறுத்துகிறது; சமத்துவமின்மையை விரிவாக்கக்கூடும்.

உலகத் தலைவர்கள் காலநிலை நடவடிக்கை பற்றி விவாதிக்க உள்ள சூழலில், இந்தியாவுக்கு அதனால் என்ன ஆபத்து என்பதை நாம் காண்கிறோம்.

இந்தியாவின் பசுமை இல்ல வாயு ஜி.எச்.ஜி (GHG) உமிழ்வு

In 2014 China was the top greenhouse gas (GHG) emitter followed by the US, the EU and India.

Source: CAIT Climate Data Explorer, 2017. Country Greenhouse Gas Emissions. Washington, DC: World Resources Institute (WRI)

பசுமை இல்ல வாயுக்கள் - ஜி.எச்.ஜி (GHG) உமிழ்வில் சீனா முதலிடம் வகிக்கிறது. 2014 ஆம் ஆண்டில், அதன் உமிழ்வு 12 ஜிகா டன் (Gt) ஆக இருந்தது. சீனாவின் உமிழ்வில் நான்கில் ஒரு பங்கு அதாவது 3.2 ஜி.டி.உடன் இந்தியா நான்காவது இடத்தில் உள்ளது.

அமெரிக்காவும் ஐரோப்பிய ஒன்றியமும் ஒரே மாதிரியான உமிழ்வுகளை பதிவு செய்கின்றன அல்லது முந்தைய ஆண்டுகளுடன் ஒப்பிடும்போது சரிவைக் காண்கின்றன, வளரும் நாடுகளான சீனா, இந்தியா போன்ற நாடுகளின் உமிழ்வு அதிகரித்து வருகிறது.

தனிநபர் உமிழ்வை நாம் பகுப்பாய்வு செய்யும் போது நிலைமை மாறுகிறது.

Canada has the highest per capita emission of GHGs. India comes at number 10.

Source: CAIT Climate Data Explorer, 2017. Country Greenhouse Gas Emissions. Washington, DC: World Resources Institute (WRI)

வளர்ந்த நாடுகளான கனடா மற்றும் அமெரிக்கா போன்றவற்றில் தனிநபரின் அதிகபட்ச பசுமை இல்ல வாயு (GHG) வெளியிடுகின்றன. சீனா ஆறாவது இடத்தில் உள்ளது; மேலும் இவ்வுலகில் ஒவ்வொரு ஆறு நபர்களில் ஒருவராக உள்ள இந்தியா, பத்தாவது இடத்தில் உள்ளது.

"காலநிலை உச்சி மாநாட்டில் இந்தியாவின் நிலைப்பாடு சமத்துவத்தில் ஒன்றாகும், வளர்ந்த நாடுகள் முன்னிலை வகிக்க வேண்டும்; எங்களால் முடிந்ததை நாங்கள் செய்வோம்" என்று லாப நோக்கற்ற ஆராய்ச்சி மற்றும் ஆலோசனை அமைப்பான, டெல்லியை சேர்ந்த அறிவியல் மற்றும் சுற்றுச்சூழல் மையத்தின் - சிஎஸ்இ (CSE) துணை இயக்குநர் சந்திர பூஷண் கூறினார்.

பல ஆண்டுகளாக, யார் உமிழ்வை குறைப்பது, அதை எவ்வாறு செய்யலாம் என்பதில் நாடுகள் மோதிக் கொண்டன.

190 க்கும் மேற்பட்ட நாடுகள் ஒரே திட்டத்தை ஏற்றுக்கொள்வது என்பது, ஒரு உணவக மேசையை சுற்றி 190 பேர் உட்கார்ந்து கொள்வதற்கு சமம், அவர்கள் அனைவரும் சாப்பிட விரும்பும் ஒரேயொரு டிஷ் கொண்ட மெனுவை தான்.

கால் நூற்றாண்டு காலமாக,ஒரு முட்டுக்கட்டை என்பது அதிகமாகவோ அல்லது குறைவாகவோ உள்ளது.

2015 ஆம் ஆண்டில், அப்போதைய அமெரிக்க ஜனாதிபதி பராக் ஒபாமா தலைமையில், ஒரு ஒப்பந்தம் ஏற்பட்டது. அப்போது நாடுகள் தங்கள் உமிழ்வை குறைக்கவும், தங்கள் சொந்த இலக்குகளைத் தீர்மானிக்கவும் முயன்றன, அவை நிர்ணயிக்கப்பட்ட தேசிய பங்களிப்புகள் -என்டிசி (NDC) என்று அழைக்கப்பட்டன. பாரிஸ் ஒப்பந்தம் என்று அழைக்கப்படும் இந்த ஒப்பந்தம், ஒரு தொடக்கமாகும். உலகின் இரண்டாவது பெரிய பசுமை இல்ல வாயு உமிழ்ப்பாளரான அமெரிக்கா இந்த ஒப்பந்தத்தில் இருந்து விலகுவதாக, 2017இல் அமெரிக்க அதிபர் டொனால்ட் டிரம்ப் அறிவித்தார்.

உலகளாவிய பேச்சுவார்த்தைகளின் போது, பணக்கார நாடுகள் பெரும்பாலும் காலநிலை மாற்றத்திற்கு ஏழை மற்றும் மக்கள் தொகை மிகுந்த நாடுகளையே குறை கூறுகின்றன. ஆனால், தரவு இக்கூற்றை ஆதரிக்கவில்லை.ஆப்பிரிக்கா - உலகின் இரண்டாவது மிகப்பெரிய மற்றும் இரண்டாவது அதிக மக்கள் தொகை கொண்ட கண்டம் - உலகளாவிய கார்பன் உமிழ்வில் 2-3% பங்களிக்கிறது, ஆனால் சிறிய தீவு நாடுகளுடன் சேர்ந்து, காலநிலை மாற்றத்தால் மோசமாக பாதிக்கப்பட்டுள்ள நாடுகளில் இதுவும் ஒன்றாகும்.

கனடா, அமெரிக்கா, ஆஸ்திரேலியா மற்றும் சவுதி அரேபியா போன்ற நாடுகள் ஆசியா மற்றும் ஆபிரிக்காவில் உள்ள ஏழ்மையான நாடுகளை விட தனிநபர் உமிழ்வை அதிகம் உருவாக்குகின்றன.

நிலக்கரி மீது அதிக நம்பிக்கை

2018 ஆம் ஆண்டில், இந்தியாவின் மின்சாரத்தில் 76.42% அதிக மாசுபடுத்தும் நிலக்கரியில் இருந்து பெறப்பட்டது என்று மின்துறை அமைச்சகத்தின் ஜூன் 2018 அறிக்கை கூறுகிறது. புதுப்பிக்கத்தக்க மின்சாரம் பெறுவது வளர்ந்து வருகின்றன, ஆனால், அவை இந்தியாவில் 20 சதவீதம் மட்டுமே வழங்குகின்றன.

Much of India’s electricity comes from highly polluting coal, only 6.60% from renewables.

Source: Growth of electricity sector in India from 1947-2018, Ministry of Power, June-2018

"மின்சார உற்பத்தி என்ற பார்வையில், நாங்கள் சரியான திசையில் நகர்கிறோம்," என்று குறிப்பிடும் சுற்றுச்சூழல் மற்றும் மேம்பாட்டு மையம், சூழலியல் மற்றும் மேம்பாட்டுக்கான அசோகா டிரஸ்ட் அல்லது ஏ.டி.ஆர்.இ.இ. (ATREE) சேர்ந்த ஷோபல் சக்ரவர்த்தி, புதுப்பிக்கத்தக்கவற்றில் அதிகரித்து வரும் கவனத்தை குறிப்பிடுகிறார். போக்குவரத்து துறை என்பது கடினமானாலும், நகரங்களில் பொது போக்குவரத்தை மேம்படுத்துவதற்கு இந்தியா சிறப்பாக செய்ய முடியும் என்று அவர் மேலும் கூறினார்.

காற்று மாசுபாட்டை ஏற்படுத்தும் பல ஏரோசோல்கள் (தூசி, கடல் உப்பு அல்லது சாம்பல் போன்ற காற்றில் உள்ள திட துகள்கள்) காலநிலை மாற்றத்திற்கும் வழிவகுக்கும் என்று, மார்ச் மாதத்தில் இந்தியா ஸ்பெண்ட் கட்டுரை வெளியிட்டிருந்த நிலையில், காலநிலை மாற்றம் மற்றும் காற்று மாசுபாடு ஆகியன சிக்கல்களை மேலும் நெருக்கமாக்கின."மாசுபாட்டை வெல்ல காலநிலை மாற்ற இலக்குகளை நாம் பயன்படுத்த வேண்டும், மேலும் மாசுபாட்டை கையாள்வதற்கான சரியான கொள்கையைக் கொண்டிருக்க வேண்டும்" என்று சக்ரவர்த்தி கூறினார்.

அதேநேரம், இந்தியா முழுவதும் காலநிலை மாற்றத்தின் தாக்கம் உணரப்படுகிறது.

இந்தியாவில் பருவமழை, வெப்பநிலை மாற்றங்கள்

இந்தியாவில் மேக வெடிப்பால் அதீத மழை பெய்வது அதிகரித்து வருகிறது. 1950 முதல் 2015 வரையில், மத்திய இந்தியா முழுவதும் தீவிர மழை நிகழ்வுகள் மும்மடங்காக அதிகரித்ததாக, 2017ஆய்வில் தெரிவிக்கப்பட்டுள்ளது. இந்த அதீத கனமழையுடன், குறைந்த அல்லது மழை இல்லாத வறண்ட காலங்களின் பாதிப்பும் அதிகரித்து வருகிறது: இந்தியாவில் ஆண்டு மழையின் 85%, அதன் மழைக்காலத்தில் இருந்து தான் கிடைக்கிறது.

"இந்த மாற்றங்களை நாம் அரேபிய கடலில் வெப்பநிலை உயர்வுடன் தெளிவாக இணைத்துள்ளோம்" என்று புனேவில் உள்ள இந்திய வெப்பமண்டல வானிலை ஆய்வு நிறுவனத்தின்- ஐஐடிஎம் (IITM) காலநிலை விஞ்ஞானி ராக்ஸி மத்தேயு கோல் கூறினார். "பொதுவாக இந்திய கடல் வெப்பநிலை முழுவதும் அதிகரித்து வருகிறது" என்றார்.

புவி வெப்பமடைதல் நிலம் மற்றும் நீர் மேற்பரப்பு வெப்பநிலை இரண்டையும் அதிகரிக்கச் செய்கிறது. கடல் வெப்பநிலை அதிகரிக்கும் போது, பருவமழை வீசுவதற்கு அதிக ஈரப்பதம் கிடைக்கிறது. "இது இந்திய பருவமழையில் பெரிய அளவிலான ஏற்ற இறக்கங்களுக்கு வழிவகுக்கிறது" என்று கோல் கூறினார்.

மற்ற காரணி, விரைவான நகரமயமாக்கல் ஆகும். எல் நினோ விளைவு போன்ற உலகளாவிய காரணிகள், மழை வடிவங்களில் மாற்றங்களுக்கு வழிவகுக்கும், மற்றும் சூறாவளிகள் தீவிரத்தில் அதிகரித்து வருகின்றன; மேலும் அவர் "முனை புள்ளிகளை" அடைந்து, இந்தியாவை "காலநிலை உச்சகட்ட பாதிக்கக்கூடியதாக" விட்டுவிட்டது.

ஆண்டு சராசரி வெப்பநிலையும் இந்தியா முழுவதும் சீராக உயர்ந்துள்ளது. இந்தியா ஸ்பெண்ட் ஆகஸ்ட் 2019 கட்டுரை தெரிவித்தபடி, 2019 கோடையில், 65% இந்தியர்கள் வெப்ப அனல் காற்றால் பாதிக்கப்பட்டுள்ளனர். ஜூலை 2019 இந்தியாவிலும், உலகளவிலும் அதிகபட்சம் என்ற சாதனை படைத்தது.

The stripes show the annual average temperature for India from 1901 (left) to 2018 (right). Changes in the colour from blue to red indicate a rise in temperature.

Source: Berkeley Earth, NOAA, UK Met Office, MeteoSwiss, DWD.

காடு வளர்ப்பு என்பது வெப்பநிலையைக் குறைக்க உதவும் வழிகளில் ஒன்றாகும், ஆனால் இந்தியாவைப் போலவே, உலகம் முழுவதும் வனப்பதிகளும் அழிக்கப்பட்டு வருகின்றன.

கார்பனில் மூழ்கும் ஆபத்தில் இந்தியாவும், உலகமும்

ஆகஸ்ட் 2019 இல், “உலகின் நுரையீரல்” என்று அழைக்கப்படும், பிரேசிலின் அமேசான் மழைக்காடுகளின் பெரும்பகுதி தீப்பிடித்து நாசமானது.

2015 ஆம் ஆண்டில், 1980 களுக்கும் 2000 க்கும் இடையில் பாலைவனமாகிவிட்ட பகுதிகளில், 38 கோடி முதல் 62 கோடி மக்கள் வாழ்ந்தனர். ஆகஸ்ட் 2019 இல் வெளியிடப்பட்ட நில சீரழிவு தொடர்பான சமீபத்திய ஐ.நா. அறிக்கையின்படி, இவ்வாறு பாதிக்கப்பட்டுள்ளவர்களில் அதிக எண்ணிக்கையிலானவர்கள் தெற்கு மற்றும் கிழக்கு ஆசியாவில் உள்ளனர். மேற்கு ஆசியாவில் வறட்சியின் அதிர்வெண் அதிகரித்து வருவதாகவும், தூசி புயல்களின் அதிர்வெண் இருப்பதாக அந்த அறிக்கை கூறியுள்ளது.

இந்தியாவில் நெருக்கமான பகுதிகள், ராஜஸ்தான், மத்தியப் பிரதேசம் மற்றும் மகாராஷ்டிரா மாநிலங்கள் ஒன்று சேர்ந்த பரப்பளவுக்கு, ஏற்கனவே சீரழிந்து உள்ளதாக, இந்தியா ஸ்பெண்ட் செப்டம்பர் 2019 கட்டுரை தெரிவித்தது: இந்தியாவின் 2018-19 பொருளாதார கணக்கெடுப்பின்படி, இந்தியாவில் உள்ள அனைத்து நடவடிக்கைகளில் இருந்தும் (நில பயன்பாடு, நில பயன்பாட்டு மாற்றம் மற்றும் வனவியல் தவிர) 26.07 லட்சம் டன் பசுமை இல்ல வாயுக்களுக்கு சமமானதாகும்.

இந்தியாவின் பசுமை இல்ல வாயுகளில் உமிழ்வுகளில், எரிசக்தி துறை 73%, தொழில்துறை செயல்முறைகள் மற்றும் தயாரிப்பு பயன்பாடு 8%, விவசாயம் 16% மற்றும் கழிவுத் துறை 3% ஆகும். வனப்பகுதி, பயிர்நிலங்கள் மற்றும் குடியிருப்புகளின் கார்பன் மடு நடவடிக்கையால் சுமார் 12% உமிழ்வுகள் ஈடுசெய்யப்பட்டன.

இந்த ஏற்றத்தாழ்வை எதிர்கொள்ள இந்தியாவுக்கு கார்பனை உறிஞ்சி சேமித்து வைக்கும் காடுகள் போன்ற தற்போதைய கார்பன் மூழ்கிகளைப் பாதுகாப்பது மட்டுமல்லாமல், புதியவற்றை உருவாக்குவதும் அவசியம்.

"காலநிலை மாற்றத்தைத் தணிக்க இந்திய அரசு உறுதிபூண்டுள்ளது" என்று ஏ.டி.ஆர்.இ.இ. மற்றும் புவி பன்முகத்தன்மை மற்றும் பாதுகாப்புக்கான சூரி சேகல் மையத்தின் மூத்த பணியாளரும், நிலச்சீரழிவு தொடர்பான ஐ.நா. அறிக்கையின் இணை எழுத்தாளருமான ஜெகதீஷ் கிருஷ்ணசாமி கூறினார். "நாங்கள் தழுவலுக்கான திட்டங்களைப் பற்றியும் பேசுகிறோம். தட்பவெப்பநிலை மற்றும் காலநிலை அல்லாத அழுத்தங்களுக்கு சுற்றுச்சூழல் அமைப்புகள் மற்றும் சுற்றுச்சூழல் அமைப்பு சேவைகளின் பாதிப்புகளை, களத்தில் உள்ள கொள்கைகளும் நிர்வாகமும் கணக்கில் எடுத்துக்கொள்ள வேண்டும்” என்றார்.

இதில் நினைவில் கொள்ள வேண்டியது என்னவெனில், இந்த சிக்கல்கள் ஒன்றோடொன்று இணைக்கப்பட்டுள்ளன, மேலும் அவை குழப்பங்களில் தீர்க்கப்பட முடியாது. காலநிலை மாற்றம், வறுமை ஒழிப்பு மற்றும் வளர்ச்சி பற்றிய விவாதங்கள் பெரும்பாலும் பல்லுயிர் மற்றும் வனவிலங்குகளின் பிரச்சினைகளை மறைக்கின்றன என்று பெங்களூரின் வனவிலங்கு ஆய்வு மையத்தின் பாதுகாப்பு உயிரியலாளரும் தலைமை பாதுகாப்பு விஞ்ஞானியுமான கிருதி கரந்த் கூறினார்.

"பல சந்தர்ப்பங்களில் பல்லுயிர் பாதுகாப்பைச் சுற்றி நடைபெறும் உரையாடல்கள் ஒரு சிந்தனையாகும்," என்று அவர் கூறினார். "கார்பனைப் பிடிக்க மரத்தை காப்பது ஒரு சிறந்த முதல் படியாகும், ஆனால் காடுகள் அழிக்கப்பட்டு, வனவிலங்குகள் வேட்டையாடப்பட்டால், நீங்கள் உண்மையில் வெற்றிபெறவில்லை" என்றார்.

நாடுகள் ஒவ்வொன்றும் பிற நாடுகளின் செயல்பாட்டுக்கு காத்திருக்கையில், உலகத்திற்கோ நேரம் கடந்துவிட்டது மற்றும் 2015 பாரிஸ் ஒப்பந்தத்தின் போது ஒப்புக் கொள்ளப்பட்ட காலநிலை இலக்குகளை கூட எட்டப்படவில்லை.

உலகம், அதன் காலநிலை இலக்குகளை தொலைத்துவிட்டது

உலகளாவிய வெப்பநிலை உயர்வு 1.5 டிகிரி செல்சியஸாக கட்டுப்படுத்த 2030 ஆம் ஆண்டில் உலகின் பசுமை இல்ல வாயு உமிழ்வுகளில் 45% வரை குறைக்கப்பட வேண்டும்; மேலும் இந்த நூற்றாண்டின் நடுப்பகுதியில், நிகர உமிழ்வு பூஜ்ஜியமாகக் குறைக்கப்பட வேண்டும் என்று நிபுணர்கள் தெரிவிக்கின்றனர்.

தற்போதைய பசுமை இல்ல வாயுக்களின் அளவு தொடர்ந்தால், உமிழ்வானது வீழ்ச்சிக்கு பதிலாக உயரவே செய்யும்.

Source: World Resources Institute

காலநிலை மாற்ற பேச்சுவார்த்தைகளைப் பின்பற்றியவர்கள் பல ஆண்டுகளாக அதிகம் மாறவில்லை என்று கூறினர். இரண்டு பெரிய உமிழ்ப்பாளர்களான அமெரிக்காவும் சீனாவும் லட்சிய உறுதிப்பாட்டைச் செய்யாவிட்டால், உலகம் அதிக முன்னேற்றத்தைக் காண வாய்ப்பில்லை என்று நிபுணர்கள் வலியுறுத்தினர்.

பல ஐரோப்பிய நாடுகளும் தங்கள் 2020 காலநிலை இலக்குகளை கைவிட தயாராக உள்ளன. "இன்னும் 25 வருட செயலற்ற தன்மையை நம்மால் பொறுக்க முடியாது" என்று பூஷன் எச்சரித்தார்.

காலநிலை பேச்சுவார்த்தைகள் என்பது, அறிவியலை விட சர்வதேச இராஜதந்திரம் மற்றும் வர்த்தக போர்களைப் பற்றியது என்று நிபுணர்கள் தெரிவித்தனர். சர்வதேச அளவில், இந்தியாவின் காலநிலைக் கொள்கையும் பெரும்பாலும் ஒரே மாதிரியாகவே உள்ளது.

"தேசிய ஜனநாயகக் கூட்டணி (தே.ஜ.கூ - NDA ) மற்றும் ஐக்கிய முற்போக்குக் கூட்டணி (யுபிஏ -UPA) அரசுகள் இடையே, சர்வதேச காலநிலைக் கொள்கையில் பெரிய வேறுபாடு எதுவும் இல்லை" என்று சிஎஸ்இ-யின் சந்திர பூஷண் கூறினார். மற்ற நாடுகள் இன்னும் பலவற்றைச் செய்யக் காத்திருக்க வேண்டிய நேரம் கடந்துவிட்டது என்றும் அவர் கூறினார். "1.5-டிகிரி-சி வெப்பநிலை உயர்வைத் தவிர்ப்பதற்கான வாய்ப்பு நமக்கு உள்ளது" என்றார்.

திங்களன்று தொடங்கும் உச்சிமாநாட்டில், "துணிச்சல் நடவடிக்கை மேற்கொண்ட நாடுகளுக்கு மட்டுமே மேடை கிடைக்கும்" என்று செப்டம்பர் 18 அன்று நியூயார்க்கில் செய்தியாளர் கூட்டத்தில் பேசிய 2019 காலநிலை மாற்ற உச்சி மாநாட்டிற்கான ஐ.நா. சிறப்பு தூதர் லூயிஸ் அல்போன்சோ டி ஆல்பா கூறினார். 100 க்கும் மேற்பட்ட நாடுகள் திட்டங்களை அனுப்பியுள்ளன, அவற்றில் 15 நாடுகளுக்கு ஒரு தளம் கிடைக்கும் என்று எதிர்பார்க்கப்படுகிறது. அவற்றில் இந்தியாவும் ஒன்றா என்பது இன்னும் தெரியவில்லை.

"காலநிலை தலைமை எப்படி இருக்கும் என்பதை நாம் திங்களன்று பார்ப்போம்" என்று ஆல்பா கூறினார்.

‘காலநிலையின் தற்போதைய தழுவல்’ என்ற சர்வதேச ஒத்துழைப்பின் ஒரு பகுதியாக, இந்தியா ஸ்பெண்ட் உள்ளது; இந்த அமைப்பு, 2019 செப்டம்பர் 23இல் நியூயார்க்கில் நடைபெறும் காலநிலை உச்சிமாநாட்டிற்கு முன்னதாக, காலநிலை நெருக்கடி தொடர்பான பாதுகாப்பு அதிகரிப்பதை நோக்கமாகக் கொண்டது.

(ஷெட்டி, இந்தியா ஸ்பெண்ட் செய்தி பணியாளர்).

உங்களின் கருத்துகளை வரவேற்கிறோம். கருத்துகளை respond@indiaspend.org. என்ற முகவரிக்கு அனுப்பலாம். மொழி, இலக்கணம் கருதி அவற்றை திருத்தும் உரிமை எங்களுக்கு உண்டு.