Expenses Fell, Usage Rose After Public Healthcare Improved In 3 TN Blocks

Mumbai: Strengthening rural public health systems in three Tamil Nadu blocks made more people utilise their services while reducing their out-of-pocket expenditure on outpatient care, an assessment of a government-run pilot project by the Indian Institute of Technology, Madras (IIT-M), has found.

Thanks to better public health facilities, fewer people accessed private facilities for outpatient care, the study conducted in one block each in Krishnagiri, Pudukkottai and Perambalur districts, found.

This has clear policy implications because Indians’ out-of-pocket spending on health is the sixth highest among 50 low-middle income countries, as IndiaSpend reported on the basis of two studies published in the medical journal The Lancet. Of the Rs 290,932 crore ($42.6 billion) spent out of pocket in 2013-14, 32% or a third was for outpatient care, according to data from the health ministry.

Health costs caused 52.5 million Indians to slip into poverty in 2011--almost half the world’s population similarly impoverished each year--as IndiaSpend reported on January 30, 2018.

Yet, outpatient care was left out of the vast National Health Protection Scheme, dubbed ‘Modicare’, that Finance Minister Arun Jaitley announced in his budget speech in February 2018. The programme would provide 100 million families with an annual insurance cover of Rs 500,000 each. However, critics pointed out, by not covering outpatient care--the largest component of out-of-pocket expenditure--it would fail to help those it seeks to target.

The government’s rejoinder is that various schemes already cover out-of-pocket expenditure. The maternity care programme Janani Suraksha Yojana provides food to pregnant women and one accompanying caretaker during hospitalisation; government-run mobile medical units and ambulance services provide free transport to and from public facilities; and the public healthcare system provides free vaccines, contraceptives, drugs and tests for HIV, TB, malaria, leprosy etc., union health minister Jagat Prakash Nadda told IndiaSpend in this March 18, 2018, interview.

The intervention

In preparation for rolling out universal health coverage, the state government of Tamil Nadu launched a pilot project in early 2017 in Shoolagiri block of Krishnagiri district, Viralimalai block of Pudukkottai district and Veppur block of Perambalur district.

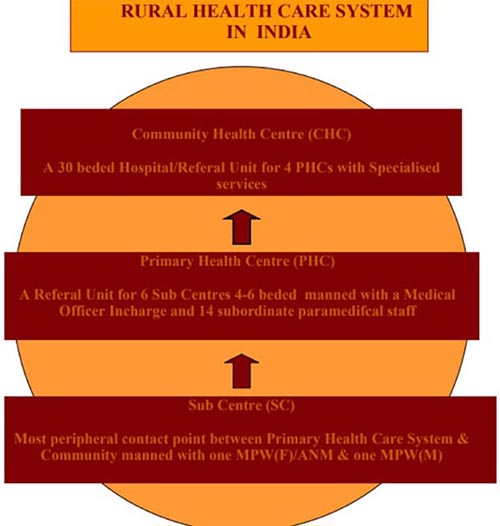

Health Sub-Centres (HSCs) are the first point of contact for rural Indians with the country’s public health system. An HSC caters to 5,000 people and is supposed to stock medicines for diarrhoea, malaria and vaccines for children. It has 3-4 staff and the capacity for basic investigations such as haemoglobin estimation and urine test for albumin and sugar.

Source: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare

However, an estimated 22% of HSCs across India are short of auxiliary nurse midwives (ANMs) and 46.4% are functioning without a male health worker, according to the 2015 rural health statistics.

Consequently, rural Indians either turn to private practitioners--58% rural Indians preferred private healthcare, according to the 71st round of the National Sample Survey--or to secondary and tertiary public facilities, which are often overburdened.

Higher up in the hierarchy are Primary Health Centres, Community Health Centres, and General Hospitals.

The pilot made sure HSCs had water, electricity and toilets, a proper consultation room and quarters for nurses. Further, staff shortages were identified and two village health nurses (VHNs) were allotted to each HSC.

Basic diagnostic services such as for blood sugar, hypertension and fever, as well as adequate drugs, were made available, including drugs for non-communicable diseases.

The results

The pilot led to a significant fall in out-of-pocket expenses for outpatient care in various public facilities--77% in Shoolagiri block (from Rs 261 per visit to Rs 59), 92% in Viralimalai (from Rs 351 to Rs 26) and 83% in Veppur (from Rs 395 to Rs 67), according to the study.

In HSCs, particularly, out-of-pocket expenditure was lesser still: Rs 5.9 per visit in Shoolagiri, Rs 2.9 in Viralimalai and Rs 5.16 in Veppur.

Utilisation of HSCs improved: 17.8% of all outpatients in Shoolagiri block, 14.8% in Viralimalai and 23.1% in Veppur used an HSC, up from just 1% before the intervention.

Source: Indian Institute of Technology, Madras

Note: PHC/CHC: Primary Health Centre/Community Health Centre

Outpatient attendance in HSCs also increased: each HSC served 10 outpatients per day in Shoolagiri, 13 in Viralimalai and 10 in Veppur. There had been fewer than three outpatients per day before the intervention.

Similarly, fewer people from these blocks sought outpatient care in private facilities. In Shoolagiri, the percentage of people who visited a private facility for outpatient care dropped from 51% to 21%; in Viralimalai from 47.8% to 24.2%; and in Veppur from 40.9% to 23.9%.

There was also a fall in the overall financial burden on patients due to expenses on drugs: until December 2017, the pilot had dispensed drugs worth Rs 10.5 lakh through HSCs to hypertension and diabetes patients.

These are two of the most common non-communicable diseases in rural India. One in five adults is affected by hypertension and one in 20 by diabetes, this March 2018 article in India Development Review said. Nearly 70% of out-of-pocket expenditure in rural areas is on medicines for non-communicable diseases, according to this August 2016 paper.

(Salve is an analyst with IndiaSpend.)

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@indiaspend.org. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.