For Rich And Poor Indians Alike, Diabetes Epidemic Shows No Sign Of Abating

Mumbai: India’s economic development has brought higher incomes--and a large helping of diabetes.

As salaries have increased, and all socio-economic groups have experienced a rise in living standards, diabetes--a condition caused by the body’s inability to regulate insulin-levels, which can lead to tissue damage and organ failure--became the country’s fastest growing disease burden over 16 years to 2016.

India currently represents 49% of the world’s diabetes burden, with an estimated 72 million cases in 2017, a figure expected to almost double to 134 million by 2025. This presents a serious public health challenge to a country facing a future of high population growth and a government attempting to provide free health insurance to half a billion people.

More money, more problems

Diabetes prevalence has increased by 64% across India over the past quarter century, according to a November 2017 report by the Indian Council for Medical Research, Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, both research institutes, and the Public Health Foundation of India, an advocacy.

In 1990, India’s per capita income was $380 (Rs 24,867), rising 340% to $1,670 (Rs 109,000) in 2016, as per data from the World Bank. Over the same period, the number of diabetes cases increased by more than 123%.

Amongst the wealthiest quintile--the surveyed group were divided into five equal groups according to wealth--2.9% of women and 2.7% of men reported they had diabetes when asked in the National Family Health Survey (NFHS) 2015-16. These rates are almost triple those found in the lowest quintile (0.8% for women and 1.0% for men).

Inactivity and the excessive consumption of high-calorie foods, both changes that accompany economic development, exacerbate diabetes’ risk factors. For this reason, diabetes is often classed as a ‘lifestyle disease’ and is found in higher numbers as populations accumulate wealth.

However, the growth in availability of fast, relatively cheap food in recent years has meant that poor diets are now found across all income brackets.

The urban poor are just as prone to diabetes as wealthier communities, according to an August 2017 study published in the Lancet Diabetes and Endocrinology journal. As incomes have increased, diets have changed to incorporate more processed food, high in sugar and salt.

Due to a lack of awareness of diabetes symptoms and risk factors compared to those in higher socio-economic groups, the poor have greater difficulty managing the disease, said leading diabetologist V Mohan in an interview with IndiaSpend in July 2017.

The disease is likely to grow among these communities, before knowledge and awareness levels improve, and they begin to tackle and prevent the illness, he said.

The increase in diabetes prevalence across India is not just indicative of an aging population. Lifestyle changes linked to an increase in wealth are impacting all age groups.

Up to 2% of women aged 15-19 years and 2.6% aged 20-25 years had high or very high blood glucose levels. In men, this rose to 2.9% and 3.7%, respectively, according to data from the NFHS 2015-16.

Currently, one in every four people under 25 has adult-onset diabetes, a condition more usually seen in 40-50 year olds, according to the Indian Council of Medical Research’s youth diabetes registry.

“Diabetes strikes Indians a decade earlier than the [rest of the] world,” Anoop Misra, chairman, Fortis Centre of Excellence for Diabetes, Metabolic Diseases and Endocrinology, New Delhi, told IndiaSpend in October 2016. “This causes reduced productivity, increased absenteeism in working population and gives more time for complications to arise.”

Wealthy states have higher incidence of diabetes

At 53 deaths per 100,000 population, Tamil Nadu had the highest death rate from diabetes among Indian states, followed by Punjab (44) and Karnataka (42), all significantly higher than the national average (23).

These states are also amongst India’s richest. Here, it is not tuberculosis or diarrhoeal diseases that are the leading causes of disability or loss of life but cardiovascular disease, high blood pressure and cholesterol.

The surge in diabetes is linked to a concurrent increase of its risk factors (potentially modifiable causes of the disease) over the same period.

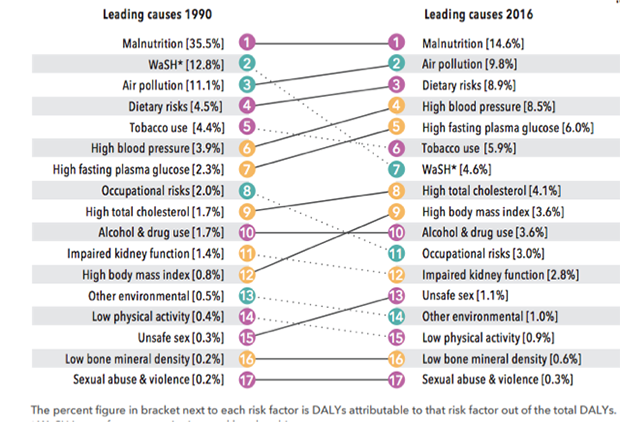

In 1990, dietary risk, high blood pressure and high plasma glucose ranked fourth, sixth and seventh, respectively, in the DALY (a measure of both early death and disability due to disease) risk factor rankings. A quarter century later, dietary risk is now third, high blood pressure fourth and high plasma glucose fifth--all of which are key contributors to the onset of type two diabetes, as the International Diabetes Foundation stated.

Change In DALYs Attributable To Risk Factors In India, 1990-2016

Source: India: Health of the Nation’s States

Again, wealthier states have higher instances of the population living with high blood pressure, high plasma glucose and dietary risk conditions. Tamil Nadu and Punjab, for instance, are consistently found in the top three DALY rate rankings for diabetes’ risk factors, while Mizoram, Arunachal Pradesh and Meghalaya--states at the lower end of the economic development scale--are consistently found in the bottom of all three categories.

How GDP affects diabetes

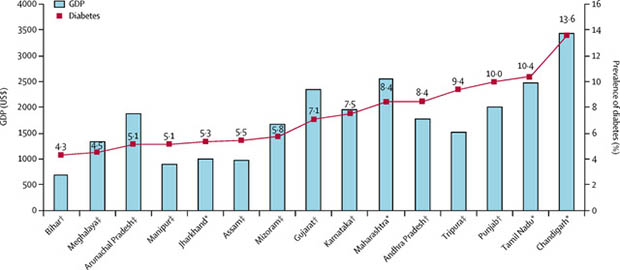

States with higher per-capita gross domestic product (GDP) have a higher prevalence of diabetes, according to a 2017 study by the Indian Council of Medical Research--India Diabetes (ICMR–INDIAB).

Of the 15 states/UTs analysed, Chandigarh had the highest GDP ($3,444) and the highest prevalence of diabetes at 13.6%. Similarly, Bihar, where GDP stands at $682, had 6% diabetes prevalence.

Diabetes Prevalence & GDP Per Capita, By State

Source: The Lancet: Prevalence of diabetes and prediabetes in 15 states of India

These findings align with the high prevalence of diabetes’ risk factors and lifestyle diseases found in wealthy states, such as Punjab, Tamil Nadu and Kerala--states with GDPs of $2,000 (Rs 1.3 lakh), $2,500 (Rs 1.6 lakh) and $2,140 (Rs 1.4 lakh), respectively. These states have the highest share of cardiovascular disease, obesity and high blood pressure, highlighting the correlation between increased income levels and illnesses caused by lifestyle changes.

Although genetic susceptibility is a key factor contributing to the onset of diabetes (the South Asian population is four times more likely to develop the disease than Europeans), environmental factors including diet have been found to contribute over 50% of the risk.

As economic growth has spread across India, studies have shown this results in an excess of calories, mainly from refined carbohydrates, in both the rural and urban population. White rice consumption, due to its high-glycaemic index which spikes insulin levels, was strongly linked to a risk of type 2 diabetes in the Indian population, according to a 2017 paper published in the British Journal of Nutrition.

An expensive trend

The annual cost to treat diabetes is estimated to be $420 (Rs 27,400) per capita, which if constant would reach an annual $30 billion (Rs 1.95 lakh crore)--over six times the 2018 health budget--by 2025, according to a report by global consulting firm PwC.

The government has recently announced its commitment to provide universal health coverage for half a billion people by 2020. Policymakers and healthcare providers are therefore concerned by a trend where the diabetes prevalence is rising as India develops, adding to the financial burden.

States with lower GDP, not immune to growing diabetes caused by a change in lifestyle and rising incomes, are faced with a double financial burden. They must tackle communicable diseases whose prevalence remains high, along with rising cases of diabetes, according to this 2017 report.

From 1990 to 2016, diabetes jumped from 37th to 15th position in a ranking of leading causes of death and disability in Uttar Pradesh, while diarrhoeal diseases and tuberculosis remained near the top, moving from first to second and third to fourth position, respectively. This highlights the disproportionate challenge faced by poorer states, who must tackle diabetes with less resources than their wealthy neighbours.

This makes a universal plan to treat and prevent diabetes across a developing India difficult. Any “policy and health system interventions to tackle their increasing burden have to be informed by the specific trends in each state”, said the India State-Level Disease Burden Initiative report.

(Sanghera is an intern with IndiaSpend.)

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@indiaspend.org. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.