How Jammu & Kashmir Is Seeing More Cases of Leishmaniasis

In recent years, Jammu and Kashmir has emerged as a new focus area of cutaneous leishmaniasis, with most cases reported from the Chenab Valley, Poonch and Rajouri districts in the Jammu division; and Kupwara and Baramulla districts in the Kashmir division.

Srinagar: Ten-year-old Muhammad Younis is in grade V and lives with his family in Kishtwar, Kashmir. Younis had sores on his nose two years ago. They were not severe, so his parents Abdul Kareem, a labourer, and Aamina Bano, a homemaker, tried home remedies. That ended up making it worse.

The sores had become crusty and infected with pus, Aamina Bano says, and their son had another sore on his left leg, which was not as severe. “After two years, we finally went to the hospital where they diagnosed him with cutaneous leishmaniasis and began treating him.”

Every week, Younis goes to Srinagar's Shri Maharaja Hari Singh Hospital for injections and to get his bandages changed. “Younis feels embarrassed about the sore on his nose. It's quite big, so whenever he goes out, he wears a cloth mask to hide it,” his elder brother Abban says.

“Leishmaniasis is a broad range of parasitic diseases caused by various Leishmania species, with clinical challenges ranging from small skin ulcers to lethal systemic infection in visceral organs, particularly the bone marrow, liver and spleen,” according to this 2021 paper in the European Journal of Pharmacology. The disease is prevalent in more than 90 countries in tropical and subtropical areas, including Asia, America and Europe.

Regarded as a neglected tropical disease, this fatal parasite has infected more than 12 million people worldwide, according to the paper. Yearly, there are 700,000 to 1.2 million new cases identified, and nearly 350 million are at risk of developing this infection globally. Around 21 Leishmania species and 30 species of sand fly vectors can transmit the infection to humans.

There are four forms of the infection: cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL), mucocutaneous leishmaniasis (MCL), visceral leishmaniasis (VL, also known as kala azar), and post kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis (PKDL). These forms differ in severity: VL is the most life-threatening, and CL is clinically identified as prominent ulcers or lesions on the skin areas like the nose, hands, forearms and legs, which are exposed to insect bites, the 2021 paper explains.

The trouble with leishmaniasis is that the mild symptoms fester for long periods, and those infected with the disease usually tend to ignore these. When they end up seeking care later, like Younis, the symptoms are much more severe.

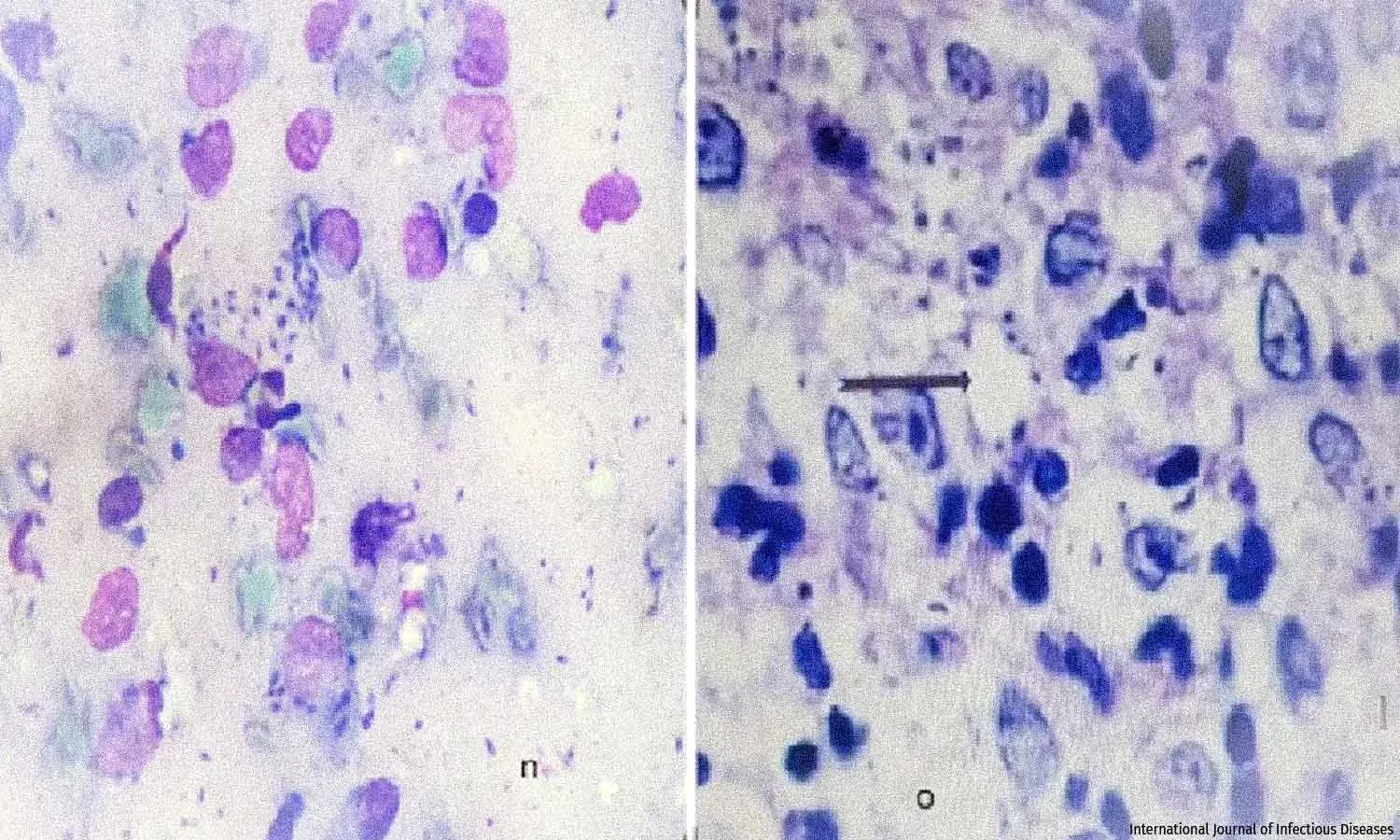

The earliest cases of CL were reported from Kashmir valley in 2009 from Tangdhar area of Kupwara district when dot-like structures appeared during microscopic examination of patient samples in a tertiary care hospital in Srinagar, Shagufta Rather, associate professor at the Postgraduate Institute of Dermatology, Venereology and Leprosy, at Srinagar’s Government Medical College, told us. Before that, such patients were unsuccessfully treated for skin tuberculosis.

Patients with parasitic disease cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) suffer psychologically, physically and economically. If left untreated, CL leaves permanent scars on patients causing them stress and often, stigmatisation.

In recent years, Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) has emerged as a new focus area of CL, with most cases reported from Chenab Valley, Poonch and Rajouri districts in the Jammu division; and Kupwara and Baramulla districts in the Kashmir division, this November 2020 paper in the International Journal of Infectious Diseases noted. This region “possesses the distinction of having hot summers and cold winters thus providing a favorable niche” for the Leishmania species, the paper, by a team of researchers led by Rather, says.

In areas endemic to CL, children account for 60%-70% of the total disease burden, Rather told us. The higher incidence could be because children are exposed to the parasite at an early age when their immune systems are still developing.

There has been a significant upsurge in the incidence of CL in J&K over the last decade, Rather said. “Initially, we received six to seven cases yearly back in 2009 at Srinagar hospital, and the numbers have risen to 60 patients [now], while around 100 cases of CL are reported yearly in Jammu.”

There have not been any comprehensive studies that provide the exact number of CL cases in J&K. But, studies, such as the one led by Rather, highlight the Union territory as a new focus of endemicity. Rather’s study collected data for 1,300 cases from two tertiary care hospitals of J&K over a period of 10 years (2009-2019). None of the patients had a history of travel to any endemic areas in the five years preceding the disease onset.

The patients suffering from CL rarely witness severe symptoms during the first six months of infection, unlike bacterial infections, which makes CL difficult to diagnose. The patients develop lesions or boils on exposed parts, like the face, followed by hands and feet, explained Shuhab Shah, a dermatologist from Srinagar currently practising in the UK. It is only during the later stages of the disease, when lesions get bigger in size or, involve eyelids, that patients report to the dermatologists. Another reason for its underreporting is that CL is more prevalent in poverty-ridden people in far-flung areas who lack access to dermatologists, and by the time they reach tertiary care, it gets late.

“The drug of choice for CL used to be sodium stibogluconate, which had very high efficacy and no side effects, but it is not easily available anywhere in the whole north India. The pharmaceutical companies no longer take interest in manufacturing the drug due to low profit which has made its [CL’s] treatment a challenging task,” said Rather.

Qazi Qamar, the deputy general of the J&K Medical Supplies Corporation Limited, told us that the department issues tenders on receiving requisitions for the drugs. “There is a possibility that companies haven’t shown interest in manufacturing this drug,” he said, adding that the department ensures the tendering process is repeated until the demand is met. In case companies do not show interest, he said, they find an alternative drug.

“We have requested WHO [World Health Organization] to make it available on a low-profit basis as it is the only time-tested drug available for the treatment of CL. The patients need to be given a 2-3 week course under proper medical supervision after which the patient shows complete recovery,” Rather said. She served as convenor for the special interest group on neglected tropical diseases under the Indian Association of Dermatologists, Venereologists and Leprologists.

The most important factor which contributes to rising cases of CL in J&K, which earlier was not an endemic for this disease, is climate change. Studies (see here and here, for instance) suggest that changes in temperature, rainfall and humidity impact its epidemiology because of their effects on population size, distribution and the survival of sandflies. The second reason for the rise in cases is population mobility, since epidemics of both CL and kala azar are often associated with migration and the movement of non-immune people into areas with existing transmission cycles, Shah told us. The third reason is deforestation and making colonies near forest zones which are suitable for sandfly vectors.

According to Diksha Kumari, a research scholar at the Infectious Diseases department at the Indian Institute of Integrative Medicine (CSIR- IIIM), Jammu, the focus should be given to identifying the species causing CL in J&K by formulating epidemiological teams. This will help discover drugs for specific target species, since there are more than 21 different species of leishmania which makes the drug discovery process challenging.

“The available drugs for Leishmaniasis pose major drawbacks such as drug resistance, exorbitant prices, etc. which makes it incumbent upon us to work in the direction of discovering a new affordable drug,” said Kumari.

Rather said that their department has worked on the clinical part and treatment response but now, they have collected samples of 50 patients diagnosed with CL which will be studied to identify species in collaboration with epidemiological teams.

The focus of the WHO is on involving dermatologists in the battle against neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) of the skin, and the target for its eradication is 2030.

As far as India is concerned, there are no solid governmental schemes to help the patients since it is prevalent among poor people who suffer to meet their daily ends, Rather told us. “There are around 20 NTDs and most of them show presence on the skin like CL, leprosy, scabies, etc. We are formulating treatment guidelines for the same and would urge the government to devise policies which would help them combat such diseases,” said Rather.

The patients with CL suffer a lot psychologically, physically and economically--the drugs are expensive and not easily available. If left untreated, the disease leaves permanent scars on the faces of patients causing them stress and often, stigmatisation.

Sahil Khan, a 22-year-old student from Rajouri, Kashmir, has CL. “It's really hard. These sores on my skin won't heal. They become crusty and sometimes infected. It's not just the pain; it's also embarrassing, especially when they're on parts of my body people can see," he said.

"People stare, and it's hard not to feel self-conscious. I just want to get better and not have to worry about these sores anymore. It's been a real struggle,” he added. “Sometimes I can't even go outside or play [cricket] with my friends because of the pain and the fear of others seeing my sores. It's like I'm trapped in my own body, wishing for relief and a normal life again," he added.

Rather stressed the immediate need to make CL notifiable by making a proper registry just like the government has done in the case of tuberculosis. “This will enable us to know the exact burden of the disease and will be a pivotal step in devising a robust strategy to combat CL. There are no prominent studies from the developing world when it comes to drug discovery of CL except recently from Sri Lanka. The government should fund the drug discovery projects and also make the drugs available for the poor masses,” said Rather.

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@indiaspend.org. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.