Hindi Outpaces English Globally: Linguistic Survey

The global growth rate of Hindi appears to have outpaced the global growth of English, according to estimates from the People’s Linguistic Survey of India (PLSI), an organization surveying Indian languages from the ground up, particularly those spoken by fragile communities.

“Over the last 50 years, the world's Hindi-speaking population has increased from 260 million to 420 million. Over the same period, the English speaking population has gone from 320 million to 480 million. These figures indicate only those who say English is their mother tongue. It does not include those who speak English for professional use as a second language,” said Ganesh Devy, Professor & Chair, PLSI.

The surge in Hindi speakers is largely due to population growth (260 million say Hindi is their mother tongue) in India's Hindi-speaking states and the Hindi-speaking diaspora scattered around the world.

According to US census 2011 data, south Asian languages experienced high growth between 2000 and 2011 in that country; Hindi grew 105% whereas Malayalam and Telugu grew by 115%.

The growth of Hindi, English and other major languages within India has come at a price: Around 250 languages in India have disappeared in the last 50 years, according to PLSI. India now has 197 endangered languages, more than any other country.

India, one of the oldest civilizations in the world, is home to hundreds of languages that primarily belong to four families, namely Dravidian, Indo-Aryan, Austroasiatic and Sino-Tibetan. Sanskrit, a classical and the oldest literary language of India dating back to the Rig Veda, has also faded in recent centuries.

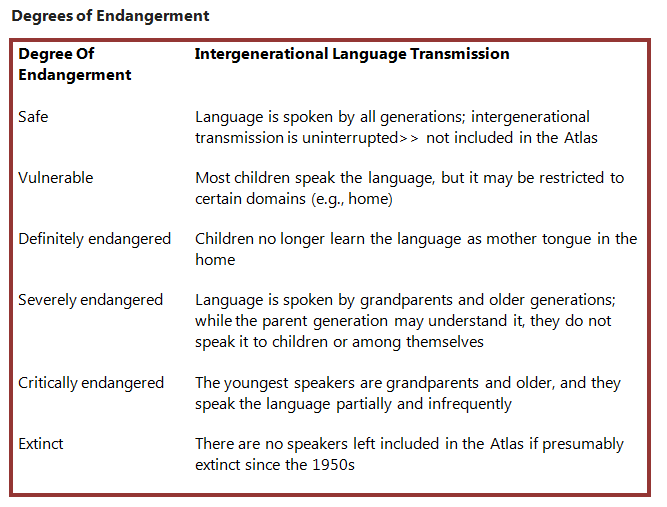

According to Prof. Devy, there are several ways of describing language endangerment (SEE BOX BELOW). According to United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), any language spoken by less than 10,000 persons is considered “potentially endangered”. Not every potentially endangered language necessarily faces the threat of immediate extinction. However, that number indicates a threshold.

Let us now look at endangered languages in India and around the world.

According to UNESCO, 197 languages in India are reported to be endangered of which 81 are vulnerable followed by definitely endangered (63), severely endangered (6), critically endangered (42) and already extinct (5).

Note: Andhra Pradesh and Maharashtra each share one language Naiki which is counted for both the states above.

Andaman and Nicobar, a union territory of India, tops the list with 11 critically endangered languages, mainly tribal dialects. Among the states, it is Manipur with seven languages, followed by Himachal Pradesh with 4 endangered languages.

The UNESCO Atlas of World’s Languages In Danger 2010 lists around 2,500 endangered languages around the world.

India, as we said, tops the list with 197 endangered languages, followed by the US (191) and Brazil (190). The US, a country that mainly speaks American English, houses numerous indigenous languages and dialects that face extinction; 74 are "critically endangered" and 54 are already extinct. Spanish is the second-most spoken language in U.S.A.

Papua New Guinea has more than 1,000 living languages, making it the country with the most spoken languages.

In India, English is thriving and is used widely by the emerging generation, which is one of the reasons leading to the threat of extinction of native or regional languages.

Dr. Deepak Pawar, Asst. Professor, Department of Civics and Politics, University of Mumbai, who is also the president of Marathi Abhyas Kendra, Mumbai (a civil society organization working for preservation and development of Marathi Language), said: “The spread of English has ... endangered the future of Indian languages and the languages of the world. English has become the language of knowledge and employability,as well as the primary language of the internet. The major content of the digital sphere is now in English, and, therefore, other languages have been marginalised. People have started considering these languages as kitchen languages."

Prof. Devy said: “The UNESCO assessment is full of errors. It includes Meiteyi (Manipuri), Khasi and Mizo, which are the main languages of the states of Manipur, Meghalaya and Mizoram. The UNESCO list needs to be seen as an indication of trends rather than as an accurate fact sheet. We need our own assessment.”

Indians do not find it necessary to learn or write in their mother tongue. This means advanced knowledge is not produced in these languages. Therefore, other languages have essentially become languages of translation. The survival of a language depends upon how assertive a linguistic community is about creating a space for its language, Pawar said.

He said general discourse around Indian languages has been literature-centric, which must change because a language can contribute to literature even if it dies in the public domain.

“We have to come out of the mindset that languages develop on their own and ensure there is an institutional mechanism for its development,” said Pawar. “Language development and planning are an integral part of preservation of language. Every linguistic community has the right to promote its language, and we have to work hard at community level, civil society and political level to ensure that a common agenda is undertaken for development of language.”

There has been no proper enumeration of languages in India for nearly a century. The last comprehensive exercise was carried out by George Grierson—an Irish linguistic scholar who carried out the first linguistic surveys in India between 1894 and 1928, listing 189 languages and several hundred dialects.

There is a general understanding that languages without scripts face the gravest threat of extinction. Prof Devy offered another view: “It is necessary to remember here that a language without a script is not necessarily a dialect. Several mighty languages in existence today do not have their own scripts. English, French, Spanish can all be counted in this class. The difference between the two is more a matter of structural identity. The Grierson Survey was carried out keeping in view the colonial administrative expediency. And, thus, it ended up reporting a lot less languages and a lot more dialects.”

Languages facing the threat of extinction in India

(Critically Endangered Languages in India; Source: LokSabha)

The PLSI reports that there are 780 “living languages” in the country. On the basis of that survey, the PLSI said that languages of the nomadic communities (branded during the colonial era as criminal tribes, now known as denotified tribes) and the languages of coastal communities in India have been on the forefront of language loss. Out of 190 such tribes, who reported to having nearly 120 of their own languages half a century ago, not more than 80 are able to recall at least the minimum vocabulary (such as the kinship terms, colour terms, names of months and days of week, etc).

The situation along India’s vast coastline is much worse. There, the main languages, those included in the 8th Schedule of the Constitution, have almost entirely replaced traditional and indigenous languages.

Indian languages that have come to prominence in recent years

Some languages have recorded significant growth in recent times, according to Prof. Devy's study. Hindi tops the chart.

Bhojpuri, spoken in Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Jharkhand and the Andamans, and in foreign countries with a Bihari diaspora, as far afield as Nepal and Surinam, is another rapidly growing language.

Some of the tribal languages, too, have recorded significant growth because of rising population. Bhilli, spoken in Gujarat, Maharashtra, Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh, shows, between 1991 and 2001, a rise of 90%.

Approximately 35 non-scheduled languages (the ones not included in the eighth schedule of the constitution) have shown a varying degree of growth, markedly higher than the actual rise in the population. These are mostly languages spoken by people who have received high-school education and can now pay attention to culture and language.

What can the government do?

The Government of India has initiated a scheme known as “Protection and Preservation of Endangered Languages of India”. The Mysore-based Central Institute of Indian Languages (CIIL) works on the protection, preservation and documentation of mother tongues/languages of India spoken by less than 10,000 speakers, depending on the degree of endangerment.

The UGC recently created Centers for Endangered Languages in 9 central universities and 11 state universities. The Ministry of Tribal Affairs has recognised the Baroda-based Bhasha Research Centre as a centre of excellence. Also, according to Prof. Devy, the Census of India has started a rapid survey of mother tongues.

Source: UNESCO

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

“Liked this story? Indiaspend.org is a non-profit, and we depend on readers like you to drive our public-interest journalism efforts. Donate Rs 500; Rs 1,000, Rs 2,000.”