Hindu, Muslim Girls Marry Earliest; Jains, Christians Later

Delhi/Mumbai: If you are a girl—educated and from an economically stable family—from an urban area, either Jain, Christian or upper-caste Hindu, the chances are you will not be married before adulthood (18 years), according to a new report.

Some other highlights:

- Teen pregnancy is nine times higher among illiterate women than among those who have finished school.

- Women from cities marry two years later than rural counterparts; the richest women marry four years later than the poorest.

- Tribal Assam, which allows younger women to have sex outside of marriage, has a high age of marriage.

The age at marriage is mostly rising within the lower castes, but at a slower pace than within the upper-castes, indicates a seven-state report from Nirantar, a Delhi-based advocacy.

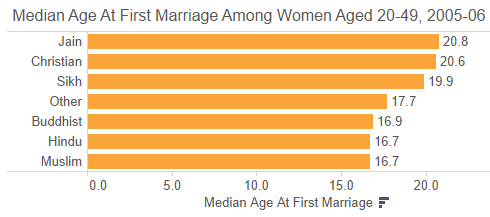

Jain women marry the latest (at a median age of 20.8 years), followed by Christian women (20.6 years) and Sikh women (19.9 years). Hindu and Muslim women have the lowest median age at first marriage (16.7 years).

Source: National Family Health Survey 3, 2005-06

Hindus and Muslims together account for 973 million, or 80% of India’s 1.2 billion people, according to the 2011 census.

Teenage pregnancies and motherhood are higher for Hindus and Muslims (16 percent) than for any other religion, making clear the relationship between early marriage and teenage pregnancies.

What determines child marriage?

Family income, location (urban and rural), community, caste and education are directly correlated with an Indian girl’s age of marriage, according to the Nirantar report Early and Child Marriage in India: A Landscape Analysis.

Nirantar works especially with women from disadvantaged communities, and its report stresses the need to change attitudes, and the need to recognise and remove adolescents from the broad category of 'child'.

Although the data reveal the widespread nature of child marriage, they also show the incidence of child marriage is dropping. Only 12 percent of Indian women who married before the age of 20 were younger than 15 at the time of marriage, according to the study.

Women have always had it worst

Nearly 17 million girls between the ages of 10 and 19—6% of the age group—are married, as IndiaSpend has reported, many to older men. This is an increase of 0.9 million from the 2001 census.

The legal age for marriage is 18, so some involved may have been adults, but it is unlikely both partners were. Of these married children, 76%, or 12.7 million, are girls, according to census data. Only four million boys in this age group are married, reinforcing the fact that girls are significantly more disadvantaged.

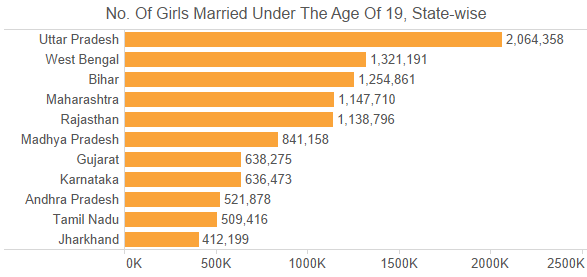

Uttar Pradesh, India’s most populous state, leads the list of states reporting child marriage:

Source: Census; *Married back in 2011

Globally, 720 million women were married before the age of 18, compared to 156 million men, a recent United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) report said. A third of these women are in India: about 240 million.

Education, income play lead roles in late marriage

Women in the highest family income bracket (this includes families that can afford all the 33 assets mentioned under a government wealth index) marry more than four years later than women in the lowest wealth quintile, according to data from the Nirantar report.

For women between 45-49 and 25-29 years, the gap in age at marriage between the highest and lowest wealth quintile widened from three and a half years, two decades ago, to five and a half years by 2007.

Among men, the age at marriage in the lowest wealth quintile is between 19.6 and 20.1 years of age, whereas among men in the wealthiest quintile, the age at marriage is between 25.3 and 26.6.

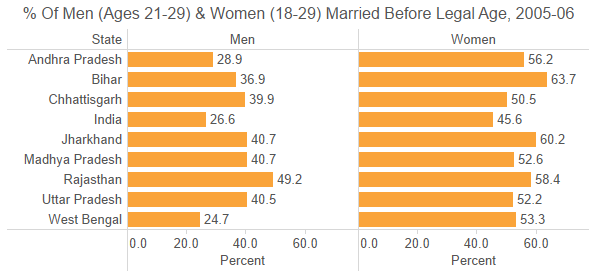

The percentage of women—between 18 and 29—married by the legal age of 18 is 45.6% and the percentage of men—between 21 and 29—married by the legal age of 21 is 26.6%.

Source: National Family Health Survey 3, 2005-06

If you live in a city, you marry later

Women from urban areas, on average, marry more than two years later than their rural counterparts, according to the Nirantar report.

The median age at marriage among urban women was 18.8 years, compared with 16.4 years among rural women. A quarter of all women aged 15-49 in urban areas have never been married, compared with 17 percent of rural women.

Among men aged 15-49, 42 percent in urban areas and 32 percent in rural areas have never been married.

Teen pregnancy 9 times higher among illiterate women

Among educated women (with at least 12 years of education) in the age groups of 25-49, it was found that there is a seven-year difference in the median age at marriage compared to those women with no education.

The level of teenage pregnancy and motherhood is nine times higher among women with no education than among women with 12 or more years of education. About 258 million Indian women are illiterate, according to the 2011 census, down from 272 million from 2001.

Marriage was the main reason for 6% of girls in rural areas and 2% of girls in urban areas dropping out of school.

Girls in Murshidabad, West Bengal, who are beneficiaries of a central government scheme SABLA that aims to improve the health and life skills of adolescent girls. Image: Nirantar

How tribal Assam delays marriage: allow sex

Another important facet of the report was its look at states with low child marriage rates such as Kerala and Assam and its attempt to draw learnings from them.

In both states, education for women and a matriarchal society were identified as two factors that have helped ensure a low percentage of girls getting married between the ages of 10 and 19, 11.7% in Kerala and 7% in Assam.

The practices of Assam’s tribal communities (which make up 12.4% of Assam’s population; Hindus are 64% and Muslims 30.9%) delink sex and marriage and allow young adults to have sex outside marriage without any social stigma.

“This has led to a higher age at marriage within these communities,” the report said. “In addition, many communities in Assam are matrilineal and hold the empowerment of their girls as a high priority.”

Similarly in Kerala, education was the prime mover for the state’s development, and its efforts to reduce poverty, and the social importance of literacy and education led to initiatives like the library movement of the mid-1930s, creating spaces for women and child-care centres as well as for political meetings.

“My story is very exciting. I was 14 when I fell in love.”

Soni (she goes by one name) giggled as she told us the story of teenage love that led to her marriage. She was not forced into it. Soni, at the age of 14, married a 16-year-old boy she met in her village Fatehnagar in southern Rajasthan.

“My father was very angry,” said Soni, now 17. She believes her life has only improved after marriage, as she no longer has to stay with an abusive aunt and uncle. Soni lives with her husband in Gujarat, where he works as a factory labourer, and clearly shares a comfortable relationship.

Soni’s story reveals the complexity of child marriage in India.

Desire and choice are often neglected as issues in the lives of teenagers, when government and NGOs address the issue of child marriage.

While the practice has affected girls’ education, their sexual and reproductive health and, in many cases, increased the likelihood of domestic violence, the debate remains open: What if adolescent girls decide that they could have a better life if they were married as early as possible?

(This story has been produced in partnership with Khabar Lahariya, a rural, weekly newspaper run by a collective of female journalists from five districts in Uttar Pradesh and one in Bihar. Each district has its own edition, brought out in the local language of the district. Salve is a policy analyst with IndiaSpend)

“Liked this story? Indiaspend.com is a non-profit, and we depend on readers like you to drive our public-interest journalism efforts. Donate Rs 500; Rs 1,000, Rs 2,000.”