How Children With Special Needs Found Their Place In Mumbai’s Classrooms

Javed Shaikh has cerebral palsy with little control over his lower limbs, hearing impairment, and a squint. He first stepped into a classroom at age 14, after a special educator under the government's Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan found Javed and counselled his family. Javed’s story reveals the possibilities of bringing education to Indian children with special needs, 594,000 of whom are out of school.

For the first 14 years of his life, Javed Shaikh’s world was confined to the four walls of his house in Kala Tanki slum in Sewri, a lower-middle class locality on the eastern edge of South Mumbai. Javed was born with multiple disabilities: He has cerebral palsy with little control over his lower limbs, hearing impairment, and a squint. He spent his days either in bed or watching TV. He could not speak and insisted on eating only Kurkure, a packaged snack.

Today, after therapy and four years in a regular school, Javed is a new person. He doesn’t like missing school, happily on his notebooks, and has friends. He can eat and dress on his own, can operate his mobile phone, can lip-read, and can even says a few words. He points at his school bag and prods his mother, Samsunisa Shaikh, if they are getting late. “I had never imagined that Javed would one day go to school,” Shaikh told IndiaSpend.

The credit for this turnaround goes in large part to Sunil Bhadane, a special educator, and to Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan (SSA)--which aims to provide quality education to every child aged 6-14 years--which Bhadane works for. He had spotted Javed near his house in Sewri one day, crawling on all fours, and had followed him home.

Javed’s story reveals the possibilities of bringing education to Indian children with special needs, 594,000 (28.2%) of whom are out of school, compared to 6 million children or 2.9% of all children who are out of school, as the first part of this series reported. The third and final part will examine the lived experience of people with disabilities through the story of a visually-challenged community living in Vangani, 60 km east of Mumbai.

The Rs 300 a day that Javed’s father made from working as a porter at the Sewri fish market was hardly enough to feed a family of five, leaving nothing for Javed’s treatment or therapy. Without adequate treatment and nutrition, Javed looked like a child of six, though he was 14 years old.

Bhadane convinced Javed’s grandmother, as the head of the family, to bring him to a health camp for children with special needs at the Jagannath Bhatankar Municipal Corporation School in nearby Parel.

There, an orthopaedic specialist examined Javed and recommended a hearing aid and leg braces, which are provided free of cost under Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan. A few days later, Bhadane visited Javed’s home again and convinced his grandmother to send him to the “school readiness” classes held at the same school premises in Parel.

That was the first time Javed stepped inside a classroom. This was a class to prepare children with special needs for school. It was here with Bhadane that Javed learned to first sit erect, to eat foods other than Kurkure, and to use the toilet by himself. He was given a hearing aid, sets of school uniform and a school bag, and was formally admitted in Prabodhankar Thackeray Municipal School in Sewri.

Inclusiveness works

The SSA follows an inclusive education model: Children with special needs study in regular classrooms, irrespective of the kind, category and degree of disability, although it does provide for home-based education for severely disabled children. Since 2012, when the Right to Education Act of 2009 was amended to provide free and compulsory inclusive education for children with special needs, there has been a steady increase in their enrolment in school.

In 2003-04, 1.7 million special-needs children were enrolled in school; in 2014-15, the figure had increased to 2.5 million, an increase of 47% over 11 years. Nevertheless, 28.2% of children with special needs remain out of school, according to this 2014 National Sample Survey of Estimation of Out-of-School Children between six and 13 years in India.

Bhadane is one of 42 special educators who look after over 16,000 children with special needs in Mumbai--one special educator per 400 children. Their job is not to teach but to track children with special needs and guide their teachers. They ensure, for instance, that children with more severe conditions such as multiple disabilities, mental retardation and cerebral palsy get more individualised attention.

Hired on contract, Bhadane earns Rs 20,000 per month--based on an allowance per child--and works six days a week.

A special educator’s day often stretches late into the evening, beyond the official day-closing at 5.30 pm. They are often called upon to go beyond the call of duty, like taking children to municipal hospitals for treatment, helping them get disability certificates and following up with officials about their aids and appliances.

Sunil Bhadane, special educator, Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan, with Javed Shaikh whom he spotted four years ago. Bhadane earns Rs 20,000 per month--based on an allowance per child--and works six days a week. His day often stretches late into the evening, beyond the official day-closing at 5.30 pm.

Among a special educator’s responsibilities are identification and assessment of children like Javed. Every year in May, a month before the start of the academic year, special educators conduct door-to-door surveys to spot children with special needs. “Parents are often in denial about the condition of their child. We have to convince and counsel them to send the child to school,” Bhadane told IndiaSpend. Other responsibilities include creating a training module with the class teacher for teaching a child with special needs and following their progress.

Starting from Kalyan in Thane district at 8 am, Bhadane reaches office in Parel, 38 km away, by 10.30 am. After dealing with some paperwork, he sets off to visit three schools every day. Since the schools are mostly in the same ward, he walks everywhere. He meets with teachers, parents and children. “We tell teachers to grade special-needs children on their abilities,” he said, explaining that different assessment criteria are to be used for special-needs and regular children.

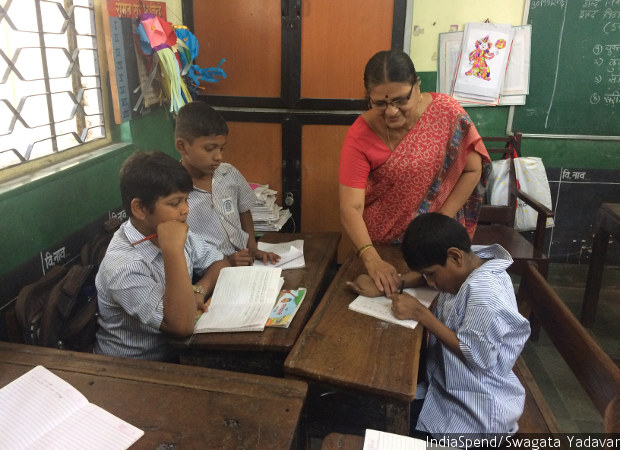

In November 2016, when IndiaSpend visited 18-year-old Javed, in school, he sat on the front bench in a grade IV classroom of the Marathi-medium Prabodhankar Thackeray Municipal School. His class teacher, Charulata Patil, was teaching general knowledge. Javed was writing alphabets in his notebook, and would smile when she called to him.

Javed Shaikh with his class teacher, Charulata Patil, in the Jagannath Bhatankar Municipal Corporation School, Parel, Mumbai. When IndiaSpend visited Javed in his school in November 2016, Javed was writing alphabets in his notebook, and would smile when Patil called to him.

“He has improved so much over the years, whenever you call him, he has a smile on his face,” Patil said. She and most teachers in Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) schools have attended workshops that sensitise teachers to the different needs of each disability group, training them in using appropriate teaching techniques. “We don’t expect these children to excel academically as much as we want them to enjoy the school experience and come to school daily,” Paraji Khemnar, headmaster of the school, said.

When children with special needs study with children without disabilities, they do not just get an education but show higher levels of social interaction and communication, besides gaining academically, various studies show. Studies have also shown that inclusive classrooms do not compromise on a regular student’s education; in fact, children make greater gains in math and reading in inclusive classrooms. And children exposed to inclusion in early childhood are more understanding towards the differently abled.

Prejudice remains

It is not always easy to get children with special needs admitted in regular BMC schools. In 2006, when Deepak Khedekar brought his hearing-impaired son Sahil to Prabodhankar Thackeray School, the then headmaster refused to admit him. Khedekar tried another BMC school, Baradevi Municipal School in Sewri, where Sahil was accepted.

SSA special educators then contacted him and facilitated surgeries for Sahil’s eyes and also helped him get a hearing aid. Today, Sahil is in grade VIII and doing well. He loves cricket, and can speak clearly enough for those close to him to comprehend. “There has been 100% improvement in Sahil,” Khedekar said. “He considers himself a regular kid.”

Deepak Khedekar with his son, Sahil, who suffers from hearing impairment and studies in grade VIII at the Baradevi Municipal School, in Sewri, Mumbai.

In the same school is nine-year-old Ankita Ingle, who has no motor function in her legs. She participates in all activities except sports, and excels academically. The five members of the Ingle family live in a slum in Sewri, in a 10 foot-by-10 foot rented room on the first floor, accessible by a narrow iron staircase which Ankita has learnt to navigate on her own. Though SSA pays a nominal transport allowance to bring children to school, her parents carry her to school and back every day.

When IndiaSpend met her, Ankita recited poetry and revealed she writes poems. “I always wanted her to study in the government school in Marathi. She got admitted here without any issues,” said her father, Appaso Ingle, who works as a painting contractor and wants Ankita to become an officer with the Indian Administrative Service.

Notwithstanding the SSA’s success in Mumbai, the number of children with special needs in government schools goes down after grade IV. Yet, their number in private and unaided schools goes up after grade IV.

“Many private and unaided schools do not admit children with special needs when they are young, but they are open to admitting them when the child has already been initiated into going to school elsewhere,” said Kiran Belge, District Co-ordinator for Inclusive Education, SSA. “Also, parents who have migrated into Mumbai become financially better off after a few years in the city and can afford private school education later,” he added.

Other experts say private and aided schools are averse to making an extra effort with special-needs children, and are reluctant to enrol them for fear they will bring the school’s overall academic performance down. “Teachers in private schools often expect us to act as shadow teachers and teach children with special needs ourselves,” Bhadane said.

Resource crunch

Even without teaching duties, special educators have more work than they can handle. Bhadane and two other special educators take care of all 118 schools in Parel taluka (administrative division). “We are able to visit some schools only after a gap of three-to-six months,” special educator Vaishali Haake, Bhadane’s colleague, said.

Sometimes, the outcomes are suboptimal for reasons beyond the reach of the SSA. Three weeks after IndiaSpend met Javed, he and his family had to move to Mumbra, 38 km north in the Kalyan neighborhood of Thane district, because their slum in Sewri had been demolished. Javed no longer goes to school. “I cannot carry Javed in the train to take him to Sewri, and I don’t know if the schools here will admit him,” his mother Samsunisa Shaikh said.

Javed Shaikh with his parents Samsunisa and Abdul Rahman in their new home. Javed's family had to move to Mumbra, 38 km north in Thane district, because their slum in Sewri had been demolished. Javed no longer goes to school.

Bhadane said families’ migration is a common problem as slums are frequently demolished to make way for high-rises, and slum dwellers end up moving farther away into the suburbs. He says he had aimed for Javed to pass grade X, and then open a small shop and become self-reliant.

One and a half month after Javed’s family shifted to Mumbra, IndiaSpend visited his home to find him still out of school. His father said he had approached a private school but its teachers had refused to let Javed study in a regular school.

Two municipal schools in Thane displayed a radically different picture from Mumbai schools. For one, there were too many students and not enough teachers. “Two of our teachers were transferred to other schools, there are four classrooms with only two teachers,” Shobhana Chodghe, headmistress at school number 123 in Mumbra, said, “If a child with special needs comes here, it will be tough for him.”

“Tell him to go to a special school,” said another headmistress, Manali Patil, of school number 78. “Our children play rough and may even hurt him.”

This is the second of a three-part series on living with disability in India. You can read the first part here and the third part here.

(Yadavar is principal correspondent with IndiaSpend.)

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@indiaspend.org. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.

__________________________________________________________________

“Liked this story? Indiaspend.org is a non-profit, and we depend on readers like you to drive our public-interest journalism efforts. Donate Rs 500; Rs 1,000, Rs 2,000.”