How Gujarat Is Trying To Overcome COVID-19 Challenges

Mumbai: Gujarat has had over 18,500 COVID-19 cases, and the number of deaths in the state also continues to climb. Case fatality (deaths among those with COVID-19) stands at about 6.2%, more than twice the national average of 2.8%.

We speak to Jayanti Ravi, principal secretary, health and family welfare, Gujarat, to understand why case fatality is higher, and discuss the state’s infrastructure preparedness and response. She gives us a public health perspective, more specifically in Ahmedabad, which is facing the brunt of the pandemic.

Edited excerpts:

Could you walk us through what you are seeing beyond the numbers that you have today?

Basically, we realise that this is something unprecedented, it’s something new that the whole world and the whole country is grappling with. We are also seeing that the numbers are high. But we are also realising that, in the process, we are really building up on our capabilities.

For example, much before the first [case], we had a bit of a lead time, if I can use that word. The first case in Gujarat only happened around March 19, as against many parts of the country, which had started having cases earlier. We realise that we got a little bit of time to prepare ourselves in terms of the infrastructure.

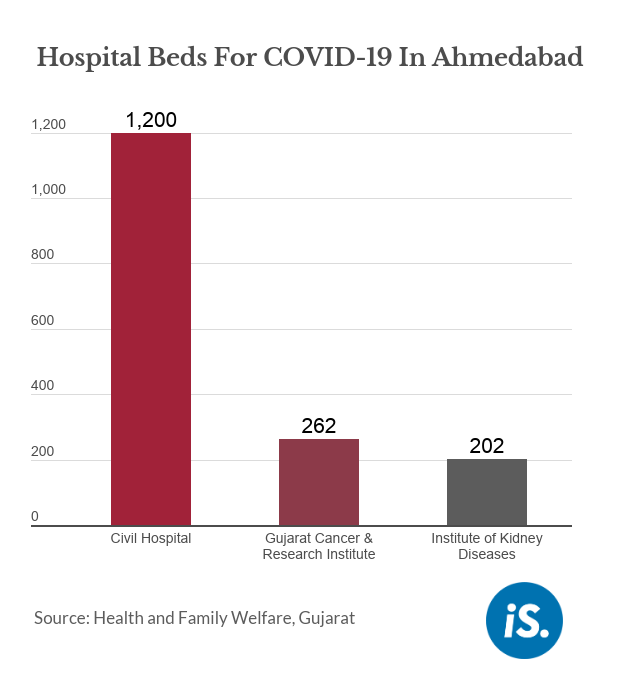

We had a brand new 1,200-bed hospital in Ahmedabad city, which was inaugurated by the honorable Prime Minister exactly a year ago. We decided to convert that into a dedicated COVID-care hospital, and similarly in four cities.

So, while on the one hand we did this preparation, we also ramped up our surveillance efforts. We were perhaps the first state originally, initially, to do a complete door-to-door survey across rural and urban areas way back at the end of March. It gave us a bit of a handle; our entire health staff was a little more primed for COVID.

Simultaneously, we also decided to build on immunity--particularly for the elderly, the comorbid and for entire populations where we found a greater possibility/probability of infection--at that time, it [the spread] was foreign traveler-based, so wherever these nuclei were there. And now, across the state, whether it’s the AYUSH--the system of Ayurveda, homeopathy--we are really pushing this also in a big way.

The other thing we are focusing on is taking a lot of help [from], and collaboration with the private sector. For example, we've had some leading pulmonologists, critical care specialists [and] intensivists who have been working with us for more than 1-1.5 months in different capacities, actually visiting our hospital on a daily basis, looking at cases, helping figure out certain better ways [of treating patients]. As a result, we have started many new practices such as this awake proning: When a patient is on ventilator care, we now use the prone position, which means the person lies on the belly. We are also doing something called telementoring. This has been going on now for about one-and-a-half months, where a group of experts is seated in Ahmedabad and we have a telementoring session every day from 12.30 p.m. to 1.30 p.m., where the ICUs dealing with COVID patients across the state are interacting with them, sharing their best practices.

And the last thing here is about research. We have invested a lot of time and efforts in different kinds of trials, interventions. For example, now tocilizumab, a medicine which is [an immunosuppressant, used to address the cytokine storm], [anticoagulants]--the fact that autopsies in Italy have shown, we understand, that this [mortality] is also because of coagulation. [We are] using these medicines also, very extensively.

What are the trends, in terms of deaths, that you are seeing? Are they different from the rest of the country? Are there any insights as to why the mortality rate is higher than in other parts of the country?

We have been doing a very detailed death audit, and we were perhaps one of the first states to put in place a detailed protocol including the use of hydroxychloroquine way back [around the end of March]; much later, even the protocol of AIIMS more or less echoed the same thing. So, we have had a team of doctors from the private sector and the government sector who have been working on all of this--protocols, etc. But if you look at the death audit, we do find that there are certain features that come out.

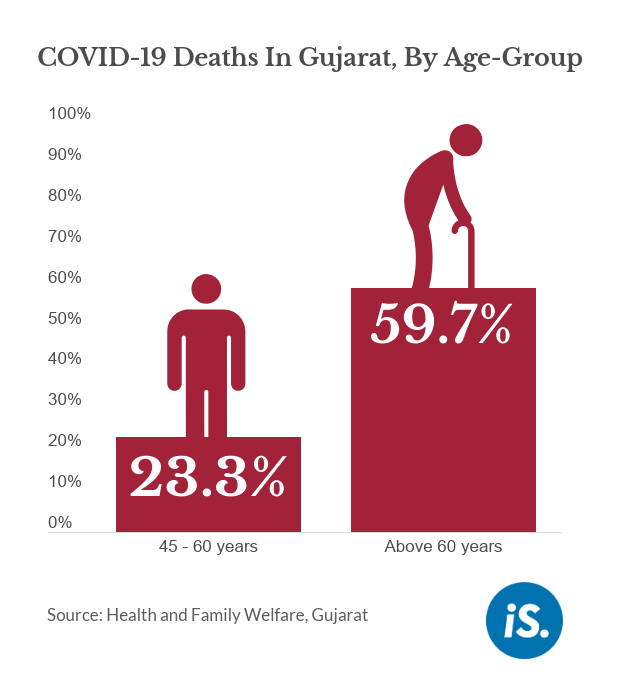

For example, nearly 83% of those that have unfortunately died belong to the age-group beyond 45 years. And 59.7% of those who have unfortunately died were more than 60 years of age.

The proportion of deceased among the really young group (1-14 years) is as low as 0.9%.

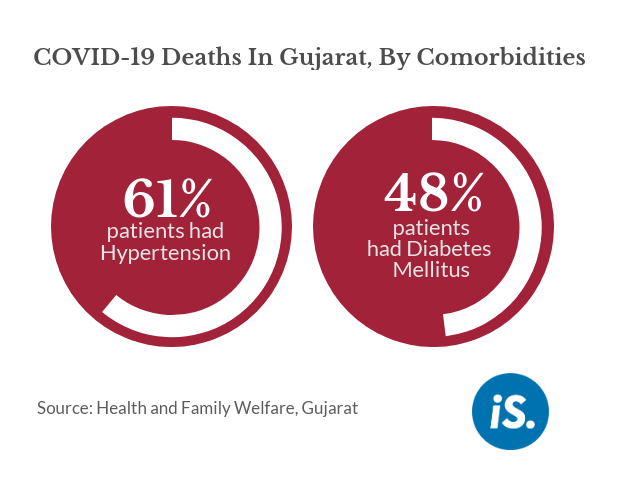

The other factor here is comorbidities. Very interestingly, we find that of those who have died, unfortunately, a majority--89% of them--were either comorbid or were in the high-risk category, that is above 60 years of age or less than 10 years of age. And here, too, a large number of them, nearly 43%, had multiple comorbidities, etc. If we look at the group that had no comorbidities and no risk factor, it is only 11%. This shows that 89% were a little more vulnerable than the rest. This is also throwing a lot of light on what is probably the underlying condition.

We have also been very transparent [and] open about reporting all the deaths. So, the numbers are more. And so if you see these numbers, they are on the higher side; but we feel that these are some of the factors.

There is another fact, which seems to be [at play]--this is still a conjecture or a surmise… but some of our top doctors, who are also experts in infectious disease, have been saying from the beginning that perhaps the strain of the virus which is here is not [the same as everywhere else]. There are two strains apparently—the S strain and the L strain. While there have been some reports to say that this may not be valid, but we still feel--and we are in the process of trying to do some more evidence-based research using the Gujarat Biotechnology Research Centre, and actually trying to see if we can identify and detect these strains and figure it out. So, the perception of these experts, some of them, is that perhaps what we have is the more virulent L strain.

Any sense on what comorbidities form the larger proportion contributing to the fatality?

We have done a detailed mapping of this. We find that the maximum--61% of those that have died--had very high blood pressure, hypertension. Then, about 48% had diabetes mellitus, again very high sugar.

Other than this, we have also [seen] comorbidities ranging from ischaemic heart disease, thyroid disorders, chronic kidney diseases, lung diseases. We have also had pulmonary TB [tuberculosis] patients and [those with] liver disorders, psychiatric illnesses, cancer, stroke and so on.

Surprisingly, we have also had people with conditions like a completely immunocompromised situation like HIV-AIDS coming out of it [recovering from COVID-19]. So, while on the one hand we do find such [comorbidities contributing to mortality], we are also seeing instances of people who have some of these and multiple comorbidities, and also elderly people coming out of it [recovering from COVID-19]. So, it's a multiplicity. It does seem a little complex.

Are any of these data points different from the other parts of the country?

I wouldn't want to venture a guess yet. We have really not done that kind of a comparison. But we are actively looking at, and we would be open to.

We have these experts, and just yesterday, we have constituted a state-level task force with nine very eminent doctors, primarily from the private sector. We also have public health experts, like Dr Dileep Mavlankar, Dr Tejas Patel, Dr Pankaj Shah who have done a lot of work on community health--not only in their capacity of cancer and so on, but also otherwise. And we have been in touch with all these experts, but we’ve still not been able to really see a very clear pattern or distinguishing feature vis-à-vis other states and other regions of India.

Walk us through your infrastructure, specifically in Ahmedabad. How many beds do you have--in private and public hospitals? At what capacity utilisation are the hospitals running? How many of them have most of their nurses and doctors?

If we talk of Ahmedabad, the first thing we set about, as I mentioned, was a brand new hospital, which was the new maternal and child health hospital with 1,200 beds. Of course, that also includes the NICU beds, etc. because you do have COVID cases--we've had a large number of deliveries of women who are COVID-positive, which have happened here; we’ve also had very complicated surgeries happening there of COVID-positive people. So, this was the first facility that we set up.

But when we felt that perhaps the ventilator beds, ICU beds, etc. needed some more expansion, we immediately roped in beds in the Medicity complex around the Civil Hospital in Ahmedabad--from the Gujarat Cancer & Research Institute, the UN Mehta Institute of Cardiology & Research Centre and the Institute of Kidney Diseases and Research Centre.

You may be aware that way back in March, we took a decision like perhaps other parts of India to try and push back some of the scheduled surgeries. We felt that planned surgeries could be pushed back, because we didn’t want nosocomial [originating in a hospital] and hospital-acquired infection etc. when we felt COVID [spread] was happening in a big way, or there was a possibility that COVID could really [spread] given that [there were] a large number of travelers from abroad. And then we also had this special point of inflection where in Ahmedabad, given the Nizamuddin event, we found that the numbers again suddenly went up. That was another factor that pushed up the numbers and these came from parts of Gujarat where it's very crowded: In a single room, you sometimes have as many as 10-15 people staying. You literally take shifts in staying--with the result [that] the spread happened much faster in some of these areas.

But given this, we decided to expand out to these other facilities. So, we have about 1,200 beds at the Civil Hospital, 262 beds--and all these are oxygen beds--at the GCRI, 202 beds at the Institute of Kidney Diseases and with excellent human resources there in terms of doctors, residents, nursing staff, the interns.

And are all their staff there? For instance, when I talk to hospitals in cities like Mumbai and Delhi, many hospitals are running at maybe 40-50% capacity because they don’t have doctors and nurses right now.

The story is similar, but I would say it’s not as bleak... in the sense that we have our basic residents, interns. We have also taken a conscious decision to push the PG [postgraduate medical] exams till after August because we want these interns and the residents primarily to continue; because they are a major, shall I say, load-bearing structure to this whole thing. While you do have faculty members, a lot of this pressure is being borne [by the residents and interns]. And they are doing outstanding work, with the result that we have a larger pool. We have the new PG students joining in by the beginning of next month.

And as far as nurses are concerned, we have also supplemented them in a very big way. Fortunately, it’s not as if the spread of the disease is monotonically or simultaneously happening across the state. We have some portions where the cases haven’t picked up; so we have places from where we have deployed a large number of doctors, residents, nurses. We are doing this constantly optimal utilisation by revolving and rotating staff from other portions [of the state]. We have also roped in the Indian Medical Association, and listed out a large number of their doctors who are available.

We also have a very large number of private hospitals across the state, and these are also available. We have come up with a very interesting pattern where 50% of the beds would be for their own private patients, for which there is a certain--these are cashless patients for the hospitals and there is a rate which is lower. So, we have this differential tariff. We are looking at possible ways of innovatively trying to think out of the box and see how we can leverage the private hospitals, their staff, infrastructure and resources also to cope with COVID.

So, have you taken over 50% of private hospital capacity in the state?

We have done this in Ahmedabad city as of now. And as I said, in almost all the districts, we have a dedicated COVID hospital as well. So, these are in addition to the public sector hospitals. So those [public hospitals] are completely taken over, or they are being dedicated for COVID. I wouldn’t use the word “taken over”, because it's their own staff which is running it in most cases. But it is something which is offered free of cost for the citizens, cashless for them, and the government is paying the bill.

You have mentioned ventilators. What is the proportion of patients who are going into critical care, and then facing the next round of problems?

If you look at those that unfortunately died, nearly 77.9% of them were on ventilators. So now, we are trying to have a more nuanced approach. One of the things that also emerges is that, if you look at breathlessness as a symptom--there are many manifestations including diarrhoea in some cases, sore throat, cough, fever--but we find that the way it’s manifesting here, [among] 85% of those that have unfortunately passed away, one of the major manifestations was breathlessness.

So, one of the things we have been doing now, over the last 1.5-2 months, is that right from door-to-door surveillance, we are fortifying all our health workers in the city and other places with pulse oximeters to see the SPO2 saturation, with enough care to make sure that this doesn’t [contribute to spread], because you are actually pegging the oximeter onto the finger. So, we are also sanitising it before it is used elsewhere.

But additionally, if you look at the hospital, with this increasing realisation that ventilators should be the last resort, we are trying to have a more nuanced approach and see if people can be put on plain oxygen. So, we are increasing the number of oxygen beds. Fortunately, we don’t have a problem of supply of oxygen or availability. Most of these beds are oxygen beds. We are also looking at the high-frequency, high-flow nasal cannula, so you can actually tweak the frequency and the volume [of oxygen] that is flowing. That’s found to give very good results.

We are also looking at the non-return breathing masks (NRBM), and then the BiPAP [bilevel positive airway pressure]. So, instead of directly having to escalate a patient, intubate them into the ventilator, we are trying to do these transitions, and really prevent having to escalate it to the ventilator, because we realised that once they go on ventilators, chances of their coming back get minimised. And again, on ventilator care, as we discussed, we are doing this awake or conscious proning, which means they lie on their belly. This is also found to show a lot of results.

Do you have enough ventilators, even as it is now accepted that we do not need as many as we thought we did? There have been some reports on the kind of ventilators and whether those are the right ones.

When we look at the context, way back in March when we were really trying to ramp up our infrastructure, we realised that the world over, this was a common cry from all these countries that there was an acute shortage of ventilators. It seemed, and it was impossible to import ventilators, which is where you get typically some of these high-end ventilators from.

So, we felt we had to also be self-sufficient. We had a meeting with the Gujarat Chamber of Commerce. When they asked us what we need, one of the facts we said was that there might be an acute shortage of ventilators. And so this led to local people--and this has happened across the country and I’m sure elsewhere in the world too, where people have tried to be really resilient and create these equipment and fabricate them so that the countries become self-reliant and are able to cope with it.

We have also had help from some of these quarters, including donations, we have had ventilators. And today, we are reasonably comfortable. We have 2,111 ventilators dedicated to COVID, which is much more than we need on an average per day--about 50 patients on ventilators. And as I said, as our understanding of the disease is getting more and more clearer, I am echoing the sentiment of our experts, the doctors, we feel that we really don’t want to use ventilators to the extent possible. So, we are getting in more of these other facilities in between being on room air to having to intubate a person.

As you look ahead, what do you think are the two or three key challenges and tasks in terms of containing this disease, and handling the lifting of the lockdown which is now underway?

There are 3-4 very interesting things that I am sure people would have noticed. One is that also in terms of patient care, one of things that happened here is being infectious hospitals, you can't have family members go there. That has been a bit of a challenge. Simultaneously, these family members are also in quarantine as a part of contact-tracing and so on. So, you had this situation which is very peculiar to this disease.

But simultaneously now, initially, you had one or two people coming in, [from] the rest of the community, and you quarantined them and so on. Now, we are giving a lot of emphasis on reverse quarantine; because you can't have 70% odd [population in quarantine]... because with the lockdown lifted or this unlock paradigm, you are going to have more and more people moving about.

But what you can do is those 10% of the people who are elderly, comorbid, if we can really ring-fence them, insulate them--and this has to come with a big social and behaviour change campaign, which we are pushing in a very big way. We are trying to see how we can fortify their immunity and how we can have pulse oximeters and such other measures on a daily basis. Those that can afford it, we can have them keep one of these at home. But otherwise, the health workers are going house to house and measuring the oxygen saturation. And again, learning to live with COVID.

It’s also a very big wake-up call for all of us to look at obesity, diabetes, hypertension, all these non-communicable diseases and look more at the preventive aspect than the curative aspect, which we have been often articulating. But it’s only when you have a situation like this that everybody gets a shake-up--as it were, unfortunately, a very hard and a very difficult shake-up. But if we really look at this, I think it could be a way of looking back at our own lifestyle and seeing what it is that we need to do.

We also realise we need more community practitioners. This whole emphasis of Ayushman Bharat, of having community health officers, is actually overwhelmingly articulating the fact that we need more people who can actually walk from the sub-centre level and ensure that the lifestyle of people, that the surveillance [and] preventive aspects are taken care of. You do need intensivists [and] cardiologists as well. But I think some of these were over-exaggerated, the importance of these vis-à-vis the others. We need both, but I think [on] the preventive side, the community side needs more [community practitioners], and similarly nurse practitioners. Because this has acutely brought out the need [and highlighted] a great shortage in terms of the qualified manpower.

So, do we really need all those academically inflated sets of skilled manpower, or could we do with a larger number of people with a smaller set of [skills], but who are really good at their job? We could even now think of having a bunch of skilled people who are maybe even class 10 or class 12 drop-outs, but if they can really be skilled on patient care, community surveillance and so on. We are really trying to tweak some of these... and with this purpose, we are also trying to simultaneously come up with a medium-term, short-term, long-term strategy for Gujarat as a whole with all these experts, to see what is it that we should be doing and where should our focus be more on. So, these are some of the learnings immediately.

But again, coming back, it’s not about fighting this virus or driving it away. I think it's about protecting ourselves. It is in our hands, literally--pun intended, too. If things like hand wash [are ensured]; if we really take care of each other and also ring-fence our elderly, which has also been a culturally inherent part of our tradition across communities; if we can again reinforce these measures and have more people from the community--religious leaders, other opinion leaders--also articulate this very clearly, I think this would go a long way. Because [a] vaccine, we don’t know, it may cost a lot; but as they say, a Rs 10 soap, a simple cotton mask would go a long way. So it's about clearly understanding it, not just by force and mandate, but if every person were to internally realise the importance, I think we can deal with it much better.

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@indiaspend.org. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.