How Production In Reliance’s KG-D6 Oil Wells Is Falling

Reliance Industries, India’s largest private sector company, is at the center of a gas pricing storm. Meanwhile, natural gas production from the company’s KG-D6 gas fields off the east coast of India continues to fall, and is a fraction of what it was three to four years ago.

Several ‘conspiracy theories’ have begun doing the rounds including one that Reliance is ‘hoarding’ the natural gas and waiting for the Government to revise the price upwards. This seems unlikely though. More likely, the gas is plain running out.

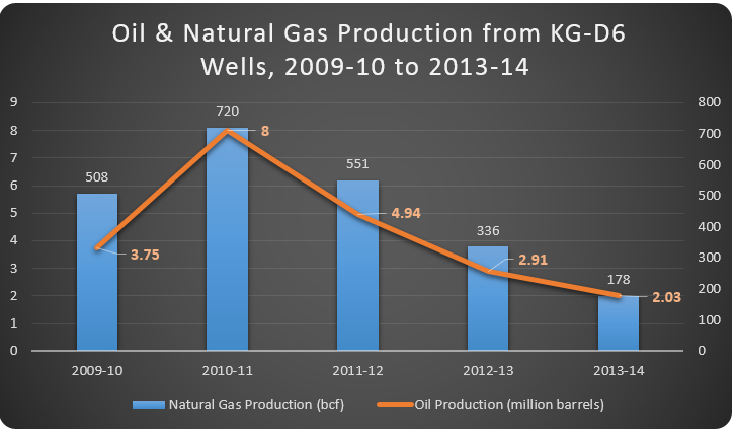

IndiaSpend tried to look at production trends, company announcements and information given out by the Government to understand the facts. Natural gas production from KG-D6 started in FY10 and saw its peak production in FY11. Ever since, natural gas and oil production has fallen every single year.

The FY14 financial results of Reliance give details of the natural gas production from the gas fields. For the full year, the KG-D6 field produced 178 billion cubic feet (bcf) of natural gas, which is less than a quarter of the production in FY11 – just after the field had become operational.

In its press release, the company attributes this fall to “the geological complexity and natural decline in the fields and higher than envisaged water ingress.” This is partly borne out by data released the Petroleum ministry, which gives out oil & gas production statistics every month.

For the year FY14, gas production from the private sector (offshore space) was much lower than the target. The bulk of this production is from the KG-D6 field of Reliance. In its latest statement, issued in April 2014, the ministry states: “A total of 10 wells in D1, D3 and 2 wells in MA have ceased to flow due to water /sand ingress in KG-DWN-98/3 field.” D1, D3 and MA are all fields in the KG-D6 block.

Older statements of the ministry going back a couple of years also refer to well closures because of this factor – the number of wells that have had to be closed has kept on increasing over the years. Water/sand can leak into oil & gas wells for a variety of reasons. One possible factor is that the pressure of oil/gas inside the well has fallen to a low level, and is not enough to keep these out. Low pressure can be a sign of the well running low on hydrocarbons. Water and sand ingress into a well is not something the field operator can usually control.

The other factor of note is that the reserve estimates of the KG-D6 have also been downgraded once. In any oil & gas field, reserves are classified in different ways. There is the ‘in-place’ reserve – which is the total quantity of oil & gas, present underground, and then there are the ‘recoverable reserves’, which can be produced at the current level of technology and prices.

In August 2012, the Petroleum Ministry informed the Parliament that prior to commencing the work on the KG-D6 gas fields, the operator (Reliance) had estimated the recoverable reserves as 10.3 tcf (trillion cubic feet) for D1 & D3 fields and 681.4 bcf for MA field.

Subsequently, the recoverable reserves were revised to 3.1 tcf for D1 & D3 fields and 788 bcf for MA field. Effectively, this means that the company had originally pegged the gas reserves at 10.98 tcf – and had planned accordingly. These reserves, after re-evaluation, came down to 3.98 tcf – less than half of the original estimate.

This also implies that in the past five years, nearly 60% of the recoverable gas from this field has already been produced. Meanwhile, the company made its capital investments keeping in mind the earlier estimates – which turned out to be optimistic. And that is perhaps where the story ends, for now.

We would like to add (as would anyone in such a case) that there is no way to look under thousands of feet of rock and be 100% sure of what lies underneath. Oil & gas companies rely on methods such as seismic surveys – which involve shooting sound waves into the ground and recording their echoes – to judge underground rock structures.

Scientists try to map the underground using these echoes, and then drill test wells to check their assumptions. These methods can and do go wrong at times.