How Solar-Powered Health Centres Could Transform Indian Healthcare

More than 50% more patients were admitted and almost twice the number of babies were delivered in a month in solar-powered primary health centres (PHC)s in Chhattisgarh, compared to those without a solar system, said a new report, illustrating how key electricity--or the lack of it--is to healthcare.

More than 60% of all primary health centres (PHCs) in Chhattisgarh reported that childbirths, laboratory and in-patient services were “severely affected” due to a lack of electricity, according to Powering Primary Healthcare through Solar in India - Lessons from Chhattisgarh, released on August 31, 2017, by the Council On Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW), a New Delhi based non-profit.

About 90% of Chattisgarh PHCs reported power cuts during peak hours, impeding public health services, such as births, vaccine storage, emergency services and clean water, said the report, which argues for alternative energy sources during power cuts, with solar being a cleaner and more cost-effective option to most.

“The lack of adequate and quality water supply compromises the ability to provide basic, routine services... and weakens the ability to prevent and control infections,” said the report.

One in every three PHCs in Chhattisgarh--a power-surplus state--and one in every two PHCs in India is either without electricity or suffers from irregular power supply, said the CEEW report.

A largely rural state, Chhattisgarh has health indicators mostly below the Indian average and its PHCs largely mirror thousands of others across India’s poor, populous northern regions.

Chhattisgarh’s struggle to provide healthcare

Fewer babies (67%) are delivered in healthcare institutions in rural Chhattisgarh than the national average (75%), according to the 2015-16 National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4), the latest available data.

Chhattisgarh’s infant mortality rate was 41 deaths per 1,000 live births in 2015, among India’s bottom 10 states, according to the Sample Registration System Statistical Report 2015, the latest available data.

No more than 66% of PHCs in Chhattisgarh are regularly supplied with electricity, the CEEW report said.

Source: CEEW Analysis, 2017

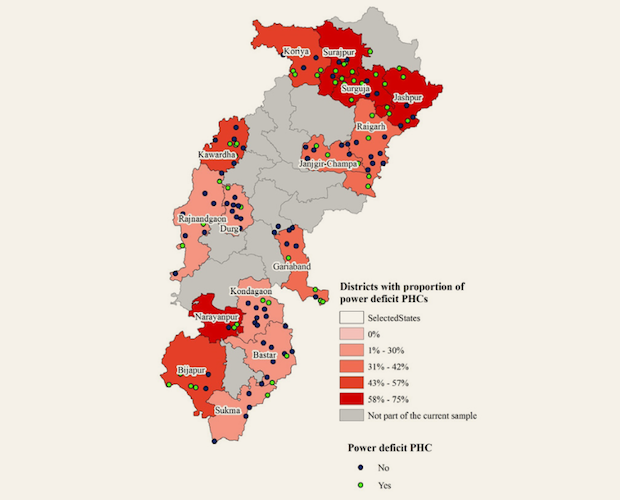

To improve electricity supply to PHCs, state agencies installed off-grid solar photo-voltaic (PV) systems of 2 kW each across 570 PHCs between 2012 and 2016. CEEW studied 147 PHCs--83 solar and 64 non-solar--across 15 of 27 districts in Chhattisgarh.

The PHCs were classified into two sub-groups--(1) power-deficit PHCs with electricity for 20 hours or less a day; (2) non-power-deficit PHCs with electricity for more than 20 hours a day--to understand the relationship between electricity access and delivery of healthcare services.

90% of the PHCs reported power cuts during peak working hours

Access to electricity is crucial for public-health services, as we said.

About 7.2% of the PHCs in Chhattisgarh have no access to electricity, against the national average of 4.6%, according to Rural Health Statistics 2016, which the report quoted. CEEW’s own analysis found 9% of 147 PHCs surveyed without electricity.

About 90% of the PHCs reported power cuts between 9 am and 4 pm, peak working hours; and nearly one-third of power-deficit and power non-deficit PHCs reported power cuts in the evening.

District-Wise Power-Deficit Primary Health Centres In Chhattisgarh

Source: CEEW Analysis, 2017

Electricity was supplied to PHCs for an average of 20.5 hours, the quality varying across districts. Voltage fluctuations were reported by 28% PHCs, and nearly 22% suffered equipment damage due to these fluctuations.

About a third or 36% of PHCs surveyed did not have enough electricity for their needs: 37% reported that water supply was affected.

About 59% of power non-deficit and 55% power-deficit PHCs have a solar system, indicating the scope for prioritisation of solar for power-deficit PHCs, the report mentions.

Solar power is reliable, clean and half as cheap as diesel

The cost of a unit of electricity from a diesel generator is Rs 24–26 per kilowatt hour (kWp), or double the cost of a solar-powered battery, which costs Rs 12–14 kWp.

Of the PHCs surveyed, 56% were solar and 45% power-deficit PHCs. The solar PHCs in Chhattisgarh are off-grid systems--with electricity generated and consumed on-site--that provide enough electricity.

Source: CEEW Analysis, 2017

Many medical services, such as deliveries and emergencies at night, benefitted from solar units, and less equipment was damaged from power fluctuations in some solar-powered PHCs.

About 84% of solar-powered PHCs reported their electricity needs were met by a combination of the grid and solar. Nearly 79% of solar PHCs under the power-deficit category said that they were able to meet their electricity needs.

(Mallapur is an analyst with IndiaSpend.)

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@indiaspend.org. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.

__________________________________________________________________

“Liked this story? Indiaspend.org is a non-profit, and we depend on readers like you to drive our public-interest journalism efforts. Donate Rs 500; Rs 1,000, Rs 2,000.”