How The Lights Came Back In Kerala’s Ravaged Homes

Thiruvananthapuram, Pathanamthitta, Alappuzha and Ernakulam (Kerala): Nileena and Cherian Zachariah’s home in Kallissery in central Kerala’s Chengannur taluk became a refuge for several neighbours affected by the devastating floods that swept Kerala in August 2018. It was also a hub for relief work.

“We were lucky that our home was not damaged,” said Cherian, who moved back to Kerala in 2014 from Kuwait where he had worked for 20 years.

But the flood waters had left Chengannur without electricity. It was the worst-affected division in the state with six of seven sections flooded. By August 16, 2018, its sub-station--an electricity distribution point--had been switched off.

The Zachariahs were struggling to tend to the needs of the dozens of volunteers who slept over at their home. “Not having power was the biggest problem, especially for cooking and the use of toilets,” said Neelina.

The disaster left 2.56 million homes statewide without electricity. How the Kerala State Electricity Board (KSEB) restored power in these homes under a fortnight by mobilising and deploying every human resource at hand, including retired KSEB staff, engineering students and private electricians, doing away with red tape and questions of hierarchy and communication could be a model for every disaster-stricken state grappling with a similar problem.

The KSEB called its plan Mission Reconnect.

Update on relief efforts: CM Pinarayi Vijayan reviewed the relief & rehabilitation efforts. The population of camps have come down to 3,42,699 people in 1093 camps. Electricity has been restored for 25.04 lakh connections of the 25.6 lakh disrupted. #KeralaFloodRelief

— CMO Kerala (@CMOKerala) August 27, 2018

“The situation was unprecedented,” NS Pillai, chairman and managing director (CMD) of KSEB, told IndiaSpend. “We had to ensure that requests for materials and personnel on ground were provided without the usual delays of following government procedure.”

In the first part of this series on how Kerala is rebuilding itself post-flood, we looked at the role of a poor women’s collective. In this second part, we tell you how KSEB, which suffered a loss of nearly Rs 850 crore during the floods, dealt with the crisis. The flood waters damaged nearly 16,158 distribution transformers, 50 sub-stations, 15 large and small hydel stations, according to the KSEB data we accessed.

IndiaSpend traversed four districts--Alappuzha, Pathanamthitta, Ernakulam, and Thiruvananthapuram--to understand how the KSEB pulled off its mission.

Swimming, wading through mud, riding a boat: How wiremen reached work

The KSEB set up a state-level task force (SLTF) at its headquarters in Thiruvananthapuram consisting of a 24x7 control room. “Our primary role was to ensure communication to and from district level officials was seamless,” said Suresh Kumar C, deputy chief engineer leading the SLTF.

The challenge was to make human resource and material available at all levels of its functioning--from the control room in the state capital to section offices--and also ensure coordination between different wings of the board and between the board and external agencies.

The focus was to ensure that materials and personnel for power restoration were provided without delay: NS Pillai, chairman and managing director, KSEB.

But what ensured the mission’s success was the doggedness with which workers and volunteers made sure that they reached distressed homes and submerged villages.

“I am set to retire soon, and have never seen anything like this,” said Manikuttan, a sub-engineer with KSEB at the Chengannur division office. It was his day off but he walked into his office in a white mundu (sarong) and brown shirt. At 55, he is fit, just a few strands of grey giving away his age.

In the three days following August 15, 2018, he travelled to work in a milkman’s boat from his home around 5 km away. “Although my house wasn’t affected, I had to wade or swim till I could access transport,” he said. “For a few days we stayed in office to restore power in different parts of the sub-division.”

Source: Kerala State Electricity Board (As of September 3, 2018)

Shyam Kumar, an assistant executive engineer, is a part of the project management unit (PMU) in Haripad circle. With senior officers stranded at home or in relief camps, he and his colleagues had to coordinate the restoration of infrastructure and supply to 120,000 consumers in Haripad. “We assumed charge under the circumstances,” said Shyam Kumar.

In order to ensure efficient coordination and communication, the PMU decided that seven nodal officers would be in-charge of each section office and local electrical installations would not be activated without their knowledge. This ensured that there were no transmission issues once sub-stations were resumed and activated.

Teams of line staff, supervisors would patrol the 11-KV high transmission lines and inform nodal officers about their status and repair requirements. The officers would then communicate the information to the circle and the control room.

Retired wiremen, electricians, engineering students roped in

Volunteers from engineering colleges, retired KSEB staff and wiremen visited individual homes to check installations like meters and wiring. “Considering Onam was around the corner, we were expecting establishments to be shut,” said Kumar. “We ensured that electrical supplies, line materials, transformers and so on were moved here from other circles.”

The priority for restoration was given to hospitals, railway stations, water pumping station and the telephone department in Chengannur.

Laila NG, assistant executive engineer at the Chengannur sub-division office, could only join work by August 22, 2018. Her home was a shelter to more than 20 neighbours hit by floods. “When I joined I realised it was a matter of managing resources, both human and material,” said Laila.

Just before the floods, 11 line staff had been transferred to new locations. This meant that the new people who had joined had little knowledge of the area and the distribution network.

“During a meeting, we requested that overseers and line staff be temporarily moved back so that they could help complete the restoration works quickly,” she said. The orders were passed immediately by the board in Thiruvananthapuram.

In Alangand too, a flood-hit section of Ernakulam, line staff and supervisors were transferred back to ensure that their familiarity with the region would hasten restoration work.

Pile of electricity meters that were damaged or have been replaced in Chengannur sub-division which was among the worst affected by the August 2018 flood.

In some areas of Chengannur and Alangad, electric poles and lines had fallen into water-logged fields and wires were sagging. A team of eight KSEB staff with experience in working in water-logged areas helped resurrect the installations and pulled up the wires.

Transformers which were not damaged were charged, their oil replaced, and fuse removed to restore transmission. Nearly 99% of the 16,158 affected transformers had been restored as of September 3, 2018, as per KSEB data.

“It was the effort of our own staff, volunteers that helped us restore power within few days despite our 33 KV substation tripping due to the flood,” said Anil Kumar, assistant engineer in Alangand section.

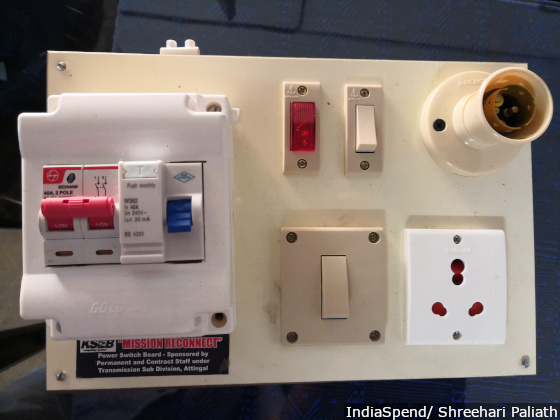

In homes where it was not possible to supply power immediately due to structural damage, simple connections were provided which included safety device to prevent shock, a power socket to use motors for cleaning or other purposes, and a bulb holder. Nearly 700 such devices were provided.

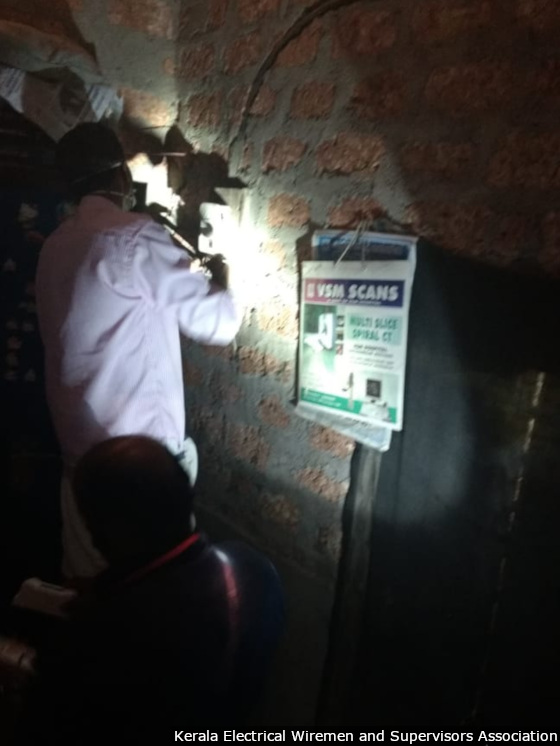

The Kerala Electrical Wiremen and Supervisors Association, a private association of electrical workers, were vital in ensuring that homes were safe for power restoration.

“A group of 3-4 people would check the wiring of close to 150 homes a day, ideally in the presence of the homeowner,” said Jose Daniel, a member of the association in Chengannur. These men were among the first to wade through the slush and mud to damaged homes, often working late into the night.

A team of wiremen like Jose Daniel would check around 150 homes a day to ensure safe wiring wiring before power restoration. They often had to wade through mud and filth to reach homes.

Low-lying areas like Kuttanad, which routinely experience flooding during rains, were even tougher po ckets to restore power.

Restoring power in Kuttanad, below mean sea level

Barely a couple of metres away from the backwater, files and papers lie strewn outside KSEB’s Kainakary office in Kuttanad. With an average elevation of 1 metre above mean sea level, it has the lowest altitude in India.

Kuttanad is used to annual waterlogging during monsoons but this was unprecedented, said locals.

During the July 2018 flood that hit parts of Alappuzha, including Kainakary, the damage had not been severe, said Anandan NK, assistant engineer, electrical section in Kainakary. “Water rose a foot inside the office in July,” he said. “But in the August flood, water rose five-feet inside the office and the strong currents damaged installations.”

The KSEB office in low-lying Kainakary, a couple of metres from the backwaters, was flooded. The substation was switched off for nearly four days.

Six of the 98 transformers in Kuttanad submerged and many others affected. The substation was switched off for nearly four days.

Small motor boats with teams of line staff and contractors cut supply to homes due to the rising waters. “With almost all the inhabitants of the region having been evacuated, patrolling at night in pitch dark was tough and dangerous,” said Ashok Kumar, a contractor with KSEB for 24 years and a flood-affected resident of Kainakary. “The clearance between the boat and the electric line was so low that we could be on the boat and check the wires in some places.”

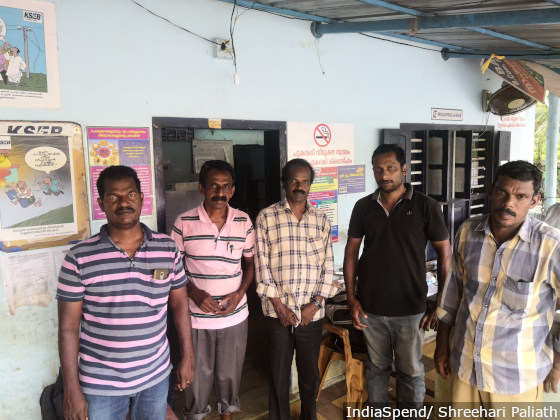

The staff at the Kainakary office that helped restore power in low-lying Kuttanad.

In the districts IndiaSpend visited, rescue teams new to the area used electric lines to identify roads and pathways.

Volunteers helped identify unsafe homes with damaged installation like meters or wiring. Wherever possible, they marked meters using stickers--red for damaged and green for undamaged--and created a checklist for reference. The entire 58-km stretch of 11 KV lines in Kuttanad, 86% of which is on paddy fields located a few metres below mean sea level, was restored in five days.

Single point connections were provided to homes where wiring was damaged or those with issues of structural stability.

“Usually, the motor pumps are used in paddy fields to deal with monsoon water-logging but most of them were damaged,” said Anandan. The need for boats also slowed down the progress. “Even now, close to 200 homes that are situated in the water-logged parts do not have power.”

Pathanamthitta and Ernakulam experienced similar issues.

Neighbouring states helped with men, material

“While the staff did an exemplary job, we received a lot of support from volunteers wiremen, and electricity staff from other state governments in the south,” said Pillai. Nearly 120 state electricity board board staff from Andhra Pradesh arrived with their own equipment to join Mission Reconnect.

KSEB received more than 20,000 electricity meters and transformers from Telangana, Tamil Nadu and Karnataka. Since the board was implementing the Integrated Power Development Scheme and Deen Dayal Upadhyaya Gram Jyoti Yojana--central schemes to improve power distribution and supply--it had a stock of electrical poles, meters and transformers it could put to use in restoration work.

“We received around 125 transformers from Tamil Nadu Generation and Distribution Corporation,” Santosh K, executive engineer in Pathanamthitta, told IndiaSpend. “More than 220 transformers were submerged here, but we were able to either replace or fix them within five days it thanks to the availability of replacement.”

The infrastructure loss alone in the district was Rs 33 crore. The KSEB has decided to not collect electricity dues till January 31, 2019, to give people time to tide over the financial distress caused by the floods.

This is the second of a three-part series. You can read the first part here and the third part here.

Next: How Kerala Staved Off A Health Crisis That The August Floods Could Have Unleashed

(Paliath is an analyst with IndiaSpend.)

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@indiaspend.org. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.