In Backward Bundelkhand, Hindutva Vs Apathy

Jhansi and Banda districts, Uttar Pradesh: In a small clearing in the Banda-Purva village in one of Uttar Pradesh’s poorest districts, a Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) supporter started a conversation on the party’s pet subject: Religion.

“We are with Lord Shri Ram. He is supreme. He has developed this world.”

When asked “What about Allah?”, he said, “Woh toh kisi ne dekha nahi (No one has seen him). But we’ve seen Ram.”

Shouldn’t Allah be recognised equally?

Another BJP supporter erupted: “Nahi. Allah nahi aatey usmey (No, Allah isn’t one of the Gods).”

“We are with Lord Shri Ram. He is supreme. He has developed this world,” says Bharatiya Janata Party supporter (forward left). When asked “What about Allah?” he said, “Woh toh kisi ne dekha nahi (No one has seen him).”

These views were not an aberration. This was election season and in meeting after meeting across Banda district, the BJP candidate R K Patel made that amply clear. He was campaigning with a local swami (monk), and a member of legislative assembly (MLA) Prakash Dwivedi. The opening lines of their campaign speeches: “This is a dharam yudh--a religious war--like the Mahabharata. A fight between good and evil.” The Narendra Modi sarkar (government) is good, the opposition collectively stands for evil. “Congress ki sarkar ne Muslim tushtikaran ke charam ko touch kiya,” said Dwivedi. “The Congress government crossed all limits of Muslim appeasement.”

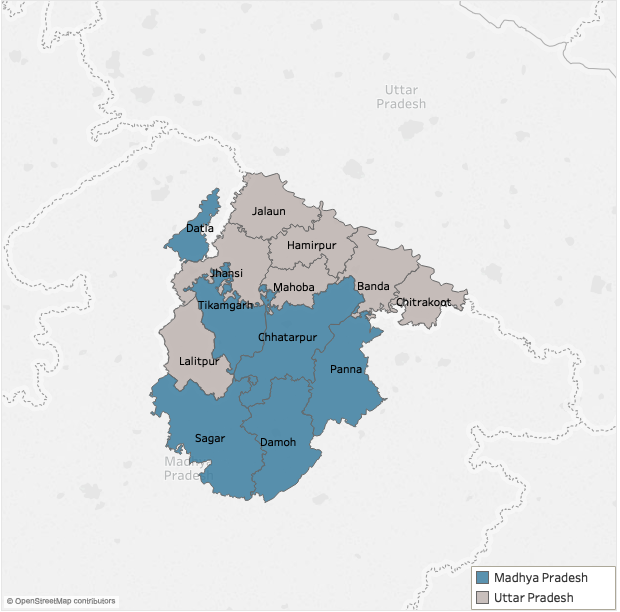

This is the Bundelkhand region--one of the most economically deprived parts of the country. This geographical zone, named after the Bundela rulers from the 14th century, is spread across two states in the present day--Uttar Pradesh (UP) and Madhya Pradesh (MP). It comprises seven districts of UP and another six in neighbouring MP.

In the half of Bundelkhand that is in UP, the seven districts are amongst the most thinly populated in the state: UP has a population density of 829 persons per sq km, while the density in the districts of Bundelkhand is just 329. This means that the districts together account for only four parliamentary seats of the 80 (5%) that UP sends to the lower house. That is a tiny number of representatives or MPs for a geographical zone that is 28.7% of the total area of Uttar Pradesh but sparsely-populated zone. Local politicians said it gives the area lesser bargaining power with which to lobby for funds from the Centre--to build road and irrigation schemes.

This is the third in a six-part series on the Hindu vote in Uttar Pradesh, India’s most hotly contested electoral battleground, which accounts for 80 of a total of 543 Lok Sabha seats (you can read the first part here and the second here). Three of four constituencies in the region--Jhansi, Hamirpur and Jalaun--vote on April 29, while Banda votes a week later on May 6.

Three of the four constituencies were listed as drought-affected by the UP government in 2018.

So, the polarising nature of BJP candidate Patel’s campaign, said political observers, is not surprising. It may make a deeply cynical voter choose the Hindu right party over the other contenders, since convincing them of any development work is an almost impossible feat.

- Population (UP + MP): 18.3 million (UP + MP); 79.1% of population lives in rural areas, and more than one-third of the households in these areas are considered to be below poverty line. Scheduled castes account for 23.5%.

- Literacy rate (UP): 69.3% (compared to India’s 74% and UP’s 67.7%)

- Per capita income index (UP): 0.280 (compared to India’s 0.522 and UP’ 0.149) (A calculation of the average income of a person in year in the area, arrived at by dividing the total income of the region by the total population)

- Urbanisation (UP): 22.4% (compared to India’s 31%). Between 2001-2011, urbanization in Bundelkhand rose from 22% to just 22.4%

- Sex ratio (UP + MP): 885 women for every 1,000 men (India average: 943)

- Child sex ratio (UP + MP): 899, declined from 914 in 2001

- Per capita income in agriculture (Both states): Rs 7,173--13.4% of national per capita income (2010-11); In UP-Bundelkhand, Rs 7,658 for agriculture.

Source: Bundelkhand Human Development Report 2012, NITI Aayog

Note: UP + MP refers to data for the combined Bundelkhand region, including districts from both Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh.

The history of under-development of the region has a lot to do with sparse rainfall and a shrinking water table. One of the markers for anyone travelling to the region are the hillsides of stark boulder and almost grey bramble and bush that pass for vegetation. The statistics tell the rest of this story. This is a drought-hit zone and, affected both by poor rainfall and, over time, a rapid depletion of groundwater. The rainfall deficit has been high, data from the National Institute of Disaster Management show.

People do not have water to drink or to water their fields. Whatever water does collect underground is getting contaminated. As much as 85% of rural India’s drinking water supply comes from groundwater, according to a 2016 study on the groundwater situation in India published in the journal Advances in Water Resources. Access to as much as 60% of that is restricted “by excess salinity or arsenic”.

Farmers, 71% of the workforce here, earn Rs 7,658 a year, on average, according to this 2016 report published by the United Nations Development Programme. That is Rs 638 a month or Rs 20 rupees a day. The farmers’ income, taken separately, is much lower than the overall income an average person in Bundelkhand earns, which according to an International Labour Organization report, is about Rs 26,805 a year--nearly four times the agrarian income.

There is virtually no sewage or garbage disposal, no jobs and the agricultural sector is suffering not just due to drought but also the apathy of successive governments, voters here said.

Lack of basic amenities triggers anger, discontent

As Patel listed schemes that the Narendra Modi government has rolled out, the anger and boredom of those gathered around was on full display. Patel described Modi as the big strong banyan tree under which they were all gathered. The next day, under the same banyan tree, in Tindwada village, in the district of Banda, villagers said they didn’t buy the speech.

“Yeh log kehtey hain dharam ki ladai hai. Koi dharam ki ladai nahi hai (These people say this is a religious war, it is no such thing),” said one farmer angrily. “Sab khokhey bata rahey hain (Those are all empty words).”

Sita Ram, a 70-year-old farmer has seen many elections come and go. “Nothing has changed here,” he said.

A third farmer was cynical enough to question what he had heard in speech after speech about Modi providing the support and strength for the Air Force to go in and strike Pakistan in retaliation for the 40 Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) members killed in Kashmir.

“Jo, madam, Modi bol rahey hain 340 jawan marey gaye wahan Pakistani... kuch batao iske barey me, ka hua? (Madam, tell me, what do you make of what is being said that 340 Pakistani terrorists were killed?)” he asked.

When he was, in turn, asked what he believed, he said, “Kis pe vishwas karein... khud pe vishwaas nahi hota hai, toh batao (Whom to believe... at this point, I don’t even believe in myself).”

The most irate were women who had to walk several kilometres, carrying drums of water on their heads, since tubewells had not reached this village.

Source: Irrigation & Water Resources Department, Government of Uttar Pradesh

Gomti is one such angry woman who explained that at the very spot where Patel had listed how Bundelkhand’s water problems would soon be a thing of the past--with the Centre sanctioning a budget of Rs 9,000 crore--is the hand pump where women are forced to bathe in full public view.

There was Rekha, a young girl in her mid-twenties, bathing in a blue salwar kameez as people walked past. “This is what it’s like to be a young woman in Tindwada,” Gomti said, her voice full of anger. “To have no bathroom and no basic dignity.”

Voters--and leaders--shift loyalties across elections

Gomti’s cynicism is part of the matrix of the overall disconnect the voters in the region experience and the fact that the BJP contender from the area, Patel, has switched parties four times in the last decade only adds to this.

Patel started out as a student in 1980 by joining the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), the BJP’s ideological parent group. But he jumped into electoral politics a decade later with a party that defines itself as the BJP’s political opposite--the dalit bastion of the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP). After losing one election, then winning the next on a BSP ticket, Patel switched to yet another party, the Samajwadi Party (SP), in 2007. He lost one election on an SP ticket and then won the next. And when the last parliamentary election came around in 2014, when the SP didn’t give him a ticket, he switched back to the BSP and lost. Soon after, he joined the BJP and contested the 2017 state election on a BJP ticket. And won.

In defence of the political criss-crossing, Patel said: “Kanshi Ram ne jo vichar dhara shuru kiya, aaj Modi ji woh vichar dhara badha rahey hain (The ideas that [BSP founder] Kanshi Ram started with have been continued and taken forward by Modi ji).”

RK Patel, the Bharatiya Janata Party’s candidate from Banda, at a campaign event. Patel cut his political teeth with the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, before getting into electoral politics through the Bahujan Samaj Party and the Samajwadi Party.

His co-canvasser and the more colourful leader from the district of Banda, the MLA Dwivedi, said: “Agar vipakshi koi kalpit kalpana pe khwaab dekh rahey hon toh mai bata doon ki woh phadey kapda gyara bajey ke bhagenge. (If the opposition is even beginning to contemplate any sort of victory, let me tell you, come counting day, 11 am, they will tear their clothes and run).”

Prakash Dwivedi, the Bharatiya Janata Party legislator from Banda district, during a campaign for the party’s Lok Sabha candidate RK Patel.

But the politics of Bundelkhand in UP is anything but a straight line between voter fatigue and the BJP’s polarisation. Despite their apathy and deep frustration, voters across all four Lok Sabha seats voted for the BJP in the last general election and have been BJP voters intermittently in state elections.

While Ravi Sharma of the BJP had won the state assembly election from Jhansi both in 2012 and 2017, Banda voted for Vivek Kumar Singh of the Congress in 2012 before voting in Dwivedi in 2017.

Source: Trivedi Centre for Political Data, Ashoka University

This time, the people of Tindwada village in the Banda constituency were ambivalent. “Yeh toh abhi nahi bata saktey kisko vote denge (We can’t say yet who we will vote for)” was the standard answer.

When probed further, some said that while they were upset with the BJP, they didn’t have much faith in any of the political alternatives. So it might just come down to a choice between voting for religion or caste, some said. Hindus may vote for what many see as the 'Hindu-leaning’ party--the BJP. Some castes and religions may vote for parties they see as the protectors of their communities--the SP or BSP.

But the picture gets more complex when the campaign in Banda district is squared with that of the more urban, slightly less economically deprived district of Jhansi.

The Jhansi formula: Jhansi = Valour = Modi

The BJP--and indeed most parties in Jhansi--lean on the valour and political history of Jhansi. The city is plastered with statues of its most famous leader of the revolt against the British in 1857, the Rani of Jhansi--used now in BJP campaigns to tell voters they have had a history of bravery, so they must vote in a government with a recent trajectory of bravery--in “giving it back to Pakistan at the border” when the country’s soldiers were attacked. In other words, Jhansi equals valour and valour equals Modi.

Uma Bharti, the BJP’s fire-brand leader who was a prominent face of the party’s Ayodhya campaign, won this seat for the party in 2014. Not only was there a Modi wave to ride on, the politics of building a temple for Lord Ram at Ayodhya, believed to be his birth-place, after the destruction of the mosque there in 1992 catapulted Bharti to the political centre-stage. This time, however, she isn’t contesting but is campaigning for the party candidate Anurag Sharma.

A town square in Jhansi district’s Lalitpur featuring statues of Rani of Jhansi, and a baby being cradled in its mother’s hands. The bill board above reads ‘Beti Bachao, Beti Padhao’, referring to the government’s flagship programme for the girl child. The BJP invokes the Rani to say the city has a history of bravery, so they must vote for a party with a record of bravery, In other words, Jhansi equals valour and valour equals Modi.

A first-time politician, Sharma is the chairman of the Baidyanath group of Ayurvedic medicines and a Harvard university graduate. His only campaign pitch is development, he said.

Stepping out of his large, green bungalow in Jhansi and into his luxury SUV, Sharma said he runs one of the largest charitable trusts in the Bundelkhand region, that is “entirely self-funded”. It made him travel to the remotest parts of the region, he said, and that is where he realised that no matter what he did--giving scholarships to 60,000 students, building borewells, sending tankers to areas that had no water--it was “just a drop in the ocean”. What was needed was “a change in the government’s policy towards Bundelkhand, someone to raise the right questions”.

He further clarified that he has “never raised a religious slogan”.

Anurag Sharma, the Harvard-educated chairman of Baidyanath group of Ayurvedic medicines, is the Bharatiya Janata Party’s Lok Sabha candidate for Jhansi. Sharma says he has “never raised a religious slogan”.

As he got to his election rally in the municipal town of Lalitpur, he stuck to what he said. His speech was short and modest. “I am Anurag,” he said, “known by most of you here as bhaiya (brother).” He listed his charitable work and ended his speech.

What Sharma did not say and did not need to was that, despite his singular push for a progressive campaign, Jhansi had already seen two decades of polarisation.

The Hindu movement in Jhansi

At the RSS office in the city, two senior leaders who spoke on the condition of anonymity, explained what the Hindu right and its umbrella of institutions from the RSS to the BJP have done. In Jhansi, the process of Hindu proselytisation began shortly after emergency rule imposed by the Congress party’s Indira Gandhi in 1975. The next big spurt was the demolition of the Babri masjid or the Ayodhya campaign of 1991-92. There are now 700 shakhas or branches across the seven districts of Bundelkhand.

And it was in this second wave post 1991, the leaders explained, that the RSS made sure the institutions of the Hindu right move beyond their upper caste base to include Dalits or scheduled caste groups--since Bundelkhand has a high dalit population (23.5%, higher than the state average of 21.1%). “We added the celebration of Valmik Jayanti (traditionally a festival of the Valmiks amongst the scheduled castes) to the RSS celebration of Sharad Poornima,” they explained.

From the year 1996 on, they also worked with the Sahariya tribes that lived mostly in and around the regions of Lalitpur and Mauranipur that are part of Jhansi district.

“In communities where backward classes were not leaders, we made them leaders, like Uma Bharti,” they explained.

In these two decades, the community work they have done has extended from the very basic--like performing the last rites for the deceased--to cow protection and, most of all, building people’s identities. That crucial task is where all the proselytisation has worked to deliver successive victories to the Hindu right’s political arm--the BJP. It includes a re-branding of the word “secular” from its traditional meaning as many understand it to be in the Indian Constitution. “We have a different understanding of that word,” they said, going over the familiar tropes. India is a Hindu nation. “Musalmaan ki topi bharatiya kab se ho gayi? (Since when did the skull cap of the Muslim become part of Indian culture?)”

This wrestle between on-ground hard-to-do development work that the RSS calls seva or volunteer work and the cultural nationalism is borne out by the next generation of Hindu nationalists as well.

Over coffee and pakoras, Saurabh Mishra, a member of the BJP’s student wing, the Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad (ABVP), had an incredible story of his rite of passage into the world of politics. It came from a self-imposed hunger strike to force a moribund administration in his village to commit to providing drinking water.

The 25-year-old is currently studying law in Jhansi, but made his way here from an extremely backward part of Bundelkhand--a village called Icholi in the neighbouring district of Hamirpur. “There was no drinking water to speak of, what we had was such hard water that is wasn’t even fit for animals,” Mishra said.

So in 2016, he decided to go on a hunger strike with his friends. Initially, this was scoffed at by people in the village.

After four days of surviving on nimbu-pani (lemonade), the sub-divisional magistrate came to try and negotiate. By this time, the protest had become a popular uprising and on the strength of that, on day 8, the district administration gave them an assurance in writing that they would ask the state to sanction a Rs 7.5 crore fund to build pipes for drinking water.

Now, in 2019, a Rs 5-crore budget to build those pipes has finally been granted, said Mishra with a broad smile. Mishra emphasised that it was his training in the ABVP that made him persevere.

Muslims and Pakistan

At the other end of the spectrum of the Hindu right is Satyam Tiwari in the Badausa region of Banda. He is part of UP Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath’s state-grown cultural nationalist outfit, the Hindu Yuva Vahini.

Tiwari sat in his mud house, narrating stories of his vigilantism: Against “love jihad”, where he stopped Hindu girls from hooking up with Muslim boys to “save them from themselves”; and for cow protection--saving cows from being slaughtered by Muslims. Two years ago, he added another feat to this list of vigilantism: Entering a school run by Muslims and demanding that they put up posters of Mahatma Gandhi and the Prime Minister on their classroom walls.

Tiwari was quick to demonstrate his Hindu-ness and accompanying aversion to everything that is Muslim. When it was pointed out that he was sitting in a room flanked by two posters of the actor Katrina Kaif who is part Muslim, he got up, took a blade to them and ripped them off the wall. “Aren’t Muslims also human beings?” this reporter asked him on camera. “Yes, they are, but they don’t have humanity,” he said.

Satyam Tiwari rips posters of Katrina Kaif off his wall after it was pointed out to him that the actor is part-Muslim. He says that sees that this kind of dramatic politics may get him the political attention he seeks.

Later, away from the camera’s eye, he said he has many Muslim friends and is also a fan of the Muslim actor Salman Khan. But, he said, he saw that this kind of dramatic politics may get him the political attention he wants.

Tiwari’s vigilantism seems like the hard end of the Hindu right’s political spectrum. But in a region of deep distress, the ‘Hindu’ factor underscores even the ideas of the BJP’s Jhansi candidate Anurag Sharma who believes that India is a “Hindu nation” and the BJP is the one party that stands for the “protection of Hinduism”.

At Sharma’s rally, there were at least 50,000 people. They weren’t there to hear what their candidate from Jhansi had to say about development. They were there because the CM Adityanath was leading the campaign.

While the crowd waited for Adityanath to arrive, a local leader tried to keep the crowd excited. He said, “Kamal par button nahi dabega toh Pakistan mazboot hoga (If you don’t press the button on the lotus [BJP’s electoral symbol], you will be strengthening Pakistan.”

Once the CM’s helicopter landed and everyone clapped, the heat took over. The crowd started to thin as Adityanath talked about how this election has been blessed by the prayers of Lord Hanuman, the strong, muscular God--Bajrang Bali--and likened it to the strong, muscular persona of the Prime Minister who led the armed forces to “attack Pakistani terrorists and finish them off”.

Farmer Hari Ram, 64, at a Bharatiya Janata Party rally in Jhansi. “No party has done anything,” he says, “But what to do? We have to vote for someone. It may as well be the present regime.”

A 64-four-year old farmer, Hari Ram from the Ghimar caste--a group classified by the government under “backward classes”--gazed into the distance. He had come to the rally riding on a tractor, from a village 25 km away. “What do I think?” he said, tuning in and out of the CM’s speech. “I have three kids, two are daily wage workers. One is handicapped. No party has done anything. But what to do? We have to vote for someone. It may as well be the present regime.”

This is the third in a six-part series on the Hindu vote in Uttar Pradesh. You can read the first part here and the second here.

(Revati Laul is an independent journalist and film-maker and the author of 'The Anatomy of Hate,’ published by Westland/Context in December 2018.)

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@indiaspend.org. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.