Indian Elections: Why Waves Don’t Matter

Data analysis for over 40 years shows that national issues or sentiments have a limited impact on votes and seats for a national party.

Amidst the current shrill, acrimonious rhetoric from political parties over a national “Modi wave”, its alleged mythical existence, and accusations of a compromised media in perpetuating it, one would think national waves make or break electoral fortunes in the Lok Sabha (LS) elections. Do national narratives or waves play an important role in determining voter preferences across states? Not really, as this analysis shows. Using the definition of a national wave as “a nationwide sentiment that can work either for or against one national party”, historical electoral data analysis reveals that waves are not probably worth squabbling over. The impact of national sentiment on vote- and seat-share has declined significantly over the last four decades as voting preferences get more local and state-specific. This analysis shows India’s national elections may not be national in its true sense but merely a series of state elections held simultaneously to elect a Central government.

It is worth acknowledging upfront, the usual cynicism about historical data analysis — the past does not predict the future, this time it is different, data does not capture sentiment, and so on. Past data equals actual results and not mere opinions collected through surveys. Historical data reveal broad trends that can be used to contextualise an argument. Thus, if this analysis shows that national waves have a declining impact on vote-share, all it merely does is put in perspective the enormity of the challenge of bucking a 40-year trend. As an ordinary data columnist, it is not my case to opine if it is achievable or not.

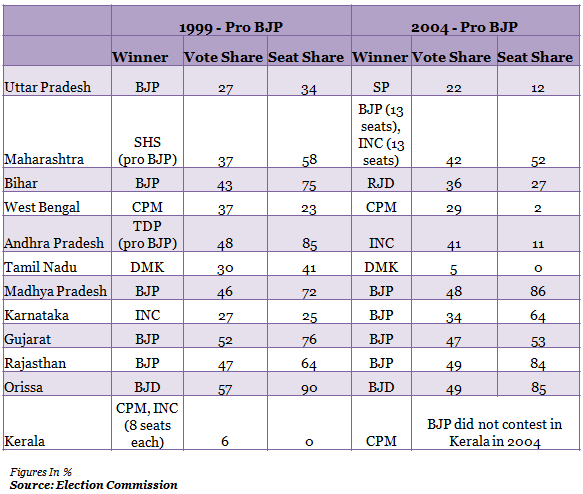

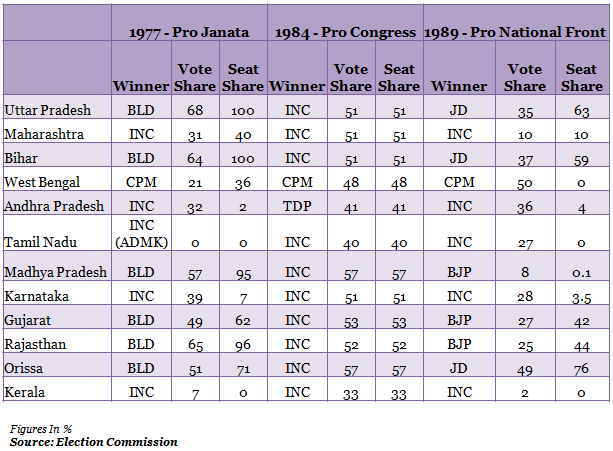

For the purposes of this analysis, I identified five “national waves or sentiments” since 1977 and the national party or alliance that was the supposed beneficiary of this wave, as per the prevailing notion then: one,1977: anti-Emergency. Pro-Lok Dal, anti-Congress; two, 1984: Indira Gandhi assassination sympathy wave. Pro-Congress; three: 1989 — Bofors and anti-corruption. Pro-National Front. Anti-Congress; four: 1999 — Vajpayee wave (after the 13 month 1998 Vajpayee government). Pro-BJP; five: 2004 — “India Shining”. Pro-BJP

The 12 largest states in the country account for 81 per cent (440) of all LS seats currently and for 87 per cent (470) of all seats until 1999 (before the partition of big states) So, an analysis of vote-share, seat-share and state-share for the national parties across these 12 states in each of the five elections will adequately answer the question: what is the impact of such national waves or sentiments on the electoral fortunes of the deemed beneficiary national party?

Over this nearly 40-year period since 1977, the analysis shows that “national issues or waves” have limited impact on vote- or seat-share for a national party. Of what impact is a wave if it cannot help its purported beneficiary to win even 50 per cent of seats (not votes)? The anti-Congress 1977 Emergency wave and the 1984 Indira Gandhi assassination sympathy wave were the last two national waves to have had a meaningful impact on vote- and seat-share margins. It is amply evident from the chart that vote-share gains in the 440 (or 470) LS constituencies across the 12 largest states for the beneficiary national party has declined significantly to 24 per cent from a high of 49 per cent. In other words, in 1984, the Indira Gandhi assassination sympathy wave helped the Congress achieve a 49 per cent vote-share vis-à-vis a 24 per cent vote-share for the BJP in the 1999 elections during the Vajpayee wave. Very interestingly, during the 2004 elections amidst the supposed “India Shining” wave, the BJP secured a 24 per cent vote-share, exactly the same as it did in 1999.

However, the BJP won merely 113 seats in 2004 as against 159 in 1999 in these 12 largest states. This difference in seats won, albeit the same vote-share in 1999 vs 2004, is explained by the choice of regional alliance partners that went awry in Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh. Analysis of the Bofors corruption scandal narrative of the 1989 elections shows very similar results — the vote-share for the purported beneficiary alliance (National Front) across these 12 states was only 25 per cent. But the National Front captured power through pre- and post-poll alliances, not through some dramatic vote- or seat-share gains due to this national wave. So then, do regional alliances matter far more than a futile chase of vote-share gains due to national narratives? The table shows it may well be the case.

An astonishing observation from the analysis is that, even during large national waves such as anti-Emergency, Indira Gandhi sympathy or Bofors scandal, the southern states and West Bengal voted as per local trends, throwing up local winners or contradicting national trends. During the height of the 1977 anti-Congress wave, of the 12 largest states, the Congress won five — Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, Andhra, Karnataka and Kerala. States like Andhra, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Kerala and West Bengal, which account for 32 per cent (171) of all LS seats, seem completely immune to any national sentiment and vote as almost separate nations in themselves. In these five “wave elections”, West Bengal has never elected the wave beneficiary party; Karnataka and Kerala only once, electing the Congress in 1984; Andhra once, when it elected the BJP in 1999 but primarily due to an alliance with the regional Telugu Desam party; and Tamil Nadu twice, when it elected the Congress in 1984 and the BJP in 1999, but again only due to regional alliances. Little wonder then that regional alliances determine winners of national elections more than any national wave or sentiment.

That India does not vote as one nation for its national elections may sound logical to those that grasp the sheer diversity of the country. The temptation to paint national narratives and hope they pervade voters across the entire nation is just plain risky and audacious. It will perhaps be appropriate to recall the nearly century-old Winston Churchill quote: “India is a geographical term. It is no more a united nation than the equator.”

This article first appeared in Indian Express.

Praveen Chakravarty is founding trustee.