Indian Police Work 14-Hr Workdays, Get Few Weekly Offs

Mumbai: “I joined the police force because of craze for the vardi (uniform),” said a station house officer (SHO) in an eastern-Mumbai police station. It was early afternoon in mid-September. The SHO was at a 12-foot desk surrounded by colleagues, talking to several people--complainants, constables and this reporter--all at once.

“It’s not like Singham,” he added quickly, referring to a popular movie. “Working in the police force is very different from what they depict in the movies. We have to work too much, are stressed and face significant external pressures.”

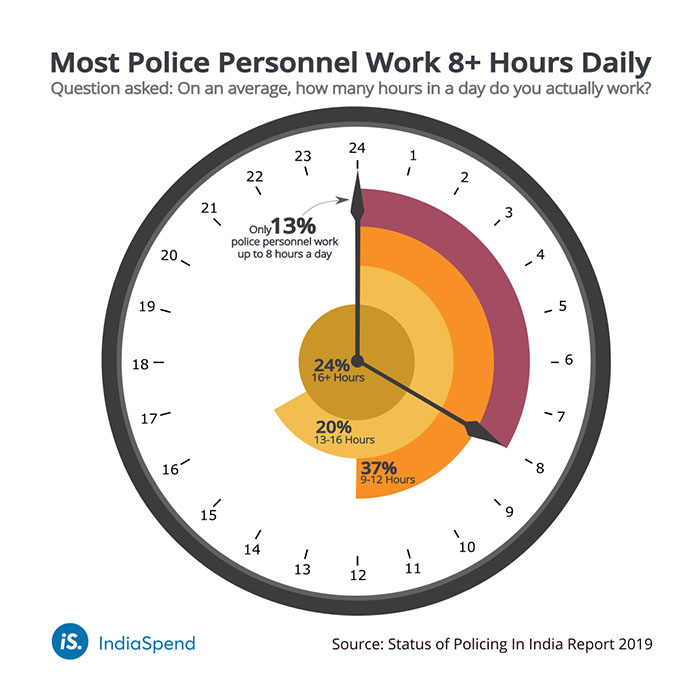

Long working hours combined with few weekly and monthly offs characterise the lives of Indian police. About 24% police personnel in India work for more than 16 hours a day, on average, and 44% work more than 12 hours, the Status of Policing in India Report 2019, released on August 27, 2019, said. A workday is 14 hours long, on average.

Further, 73% of police personnel reported that their workload is taking a toll on their physical and mental health, the study undertaken by Common Cause and Lokniti–Centre for the Study Developing Societies, a nonprofit and a think-tank, respectively, based in New Delhi, found. About 84% said their duties leave no time for their families.

‘Will not let our children join the police force’

“There are many difficulties you must endure if you work in the police,” a constable in Mumbai told this reporter, adding that he wouldn’t want his children to join the force. “There’s no value given to the time you spend, your duty,” he explained. “When I began working, whether you work for 12 hours, 15 hours, or 24 hours, you were still paid the same.”

Four in five personnel said they do not get paid for overtime work. Maharashtra is the only state to give all personnel at least one weekly off day, the study said.

How many monthly offs does the constable get? He laughed. “Kahaan sahib (Why Sir), I can barely get an off in 2-3 months.”

“They [our children] can work wherever they like, in whatever field, but I won’t let them join the police,” a sub-inspector said. “If I faced such hardship, why would I want my children also to do that? I won’t even think about it.”

“When Bal Thackeray had died, and even at some other VIP-bandobasts [security detail for important persons], we didn’t even go home for three or four days,” the sub-inspector continued. “We could only take naps [while] sitting on a chair in the police station.”

How often do they get to take a vacation? “I can’t plan for the day after tomorrow, how am I going to travel anywhere?” a sub-inspector said.

Although on paper he was required only to work 12 hours a day, an SHO said, he works 14-15 hours each day. “We’re supposed to have a holiday once every week, but that too is never certain,” he added. Counting for his commute, he works for around 17 hours per day.

He went on to describe the day of his wedding engagement. “I took a train at 11 pm, reached early in the morning around 5.30-6 am, got engaged on that day, and left the next day.”

A sub-inspector at the Shivaji Nagar police station had a similar experience on his wedding day.

“I’ve no time to spend with family,” the SHO said. “I have an 18-month-old son. When I leave for work in the morning, he’s asleep and when I return from work, he’s also sleeping.” Other sub-inspectors, much older than the SHO, had similar stories to tell, as did the sub-inspector from Sakinaka. “Our children grew up without really knowing who their father was,” they said.

“I couldn’t spend time with my family when I began, and I can’t spend time with them now,” the sub-inspector said.

“The same thing has been ongoing since the British era,” another sub-inspector said. “If I can’t spend any time with family on festive occasions, how are they going to feel?” another asked.

The situation is similar across states.

Police personnel in 21 states work for 11-18 hours daily, on average. Average working hours in Odisha are the highest, 18 hours a day, as per the results of the survey. In Nagaland, police persons worked for 8 hours a day, on average.

1 in 5 sanctioned positions vacant

As many as 22% of positions in the police force were yet to be filled as of January 2017, Bureau of Police Research and Development (BPRD) data show. This is despite a 11% rise in manpower between January 2016-January 2017.

Between 2011-2016, vacancy in the Indian police force fell from 25.4% to 21.8%, data show. Yet, as of January 2017, India’s police-population ratio was 148 police persons per 100,000 people, two-thirds the United Nations’ recommendation of 222.

“There are so many vacancies even in this station,” a constable said. “This means that if I ever want an off, I never get it. If we have enough people, we can rotate, take offs and complete all the work. But if I leave, work will just remain incomplete.”

“One person needs to work as much as ten people,” the SHO elaborated. “For example, we need at least three to four police stations in this area, but we only have one.”

“How can we cater to everybody?” another SHO asked. “We have to deal with the problems of those who are rich and affluent, as well as those who are poor, and cater to industries, residential areas and slums.”

3 in 4 police persons feel working conditions affect their health

Nationwide, 74% of police station staff and 76.3% of SHOs felt that the present working conditions impact their health. Personnel reported health issues such as hypertension, mental stress, sleeplessness, fatigue, asthma and respiratory problems, gastric trouble, and body aches, as per a 2014 report by the BPRD.

Every second police person in the national capital region complained of health issues, but only around about half (47%) of those with complaints sought any kind of treatment, a study published in 2018 in the Indian Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine showed. The most common health issues were metabolic and cardiovascular (36.2%), musculoskeletal (31.5%) and vision-related (28.1%).

A sub-inspector, who averaged around 16-17 hours of work and commute every day, felt his memory was weakening due to being overworked. A sub-inspector we spoke to felt that he was developing acidity due to unpredictable work hours and consequent irregular eating habits.

Health issues such as acidity aren’t covered in the police’s health insurance.

“Only major problems such as cardiac issues, cancer, liver problems, etc are covered in our Mediclaim,” a sub-inspector said referring to the group insurance scheme. “Health issues we face every day, like coughs and colds, malaria, dengue, typhoid, etc are not covered. We really need this. Moreover, costs are covered only if we get ourselves admitted to the hospital.”

“If there’s an emergency, we will only get costs covered if we go to the hospital approved by the government,” one of his colleagues added. “But in an emergency, anyone will just go to the nearest hospital.”

“This sahib,” he said, pointing to an officer seated at the other end of the room, “has problems with his sugar levels and had to go to a nearby doctor because he was about to pass out. But he’s going to have to pay everything from his own pocket.” There was only one hospital the government recognised in the area, he added.

An officer recounted how a few of his colleagues had committed suicide, finding it difficult to cope with the high stress that comes with the job. Another spoke of the death of a 35-year-old officer due to cardiac arrest.

On asking a sub-inspector in a police station about his insurance coverage, he looked to one of his colleagues, almost surprised, “Do we have a Mediclaim?”

4 in 5 personnel do not get paid for overtime work

Four in five personnel said they do not get paid for overtime work, the CSDS-Lokniti report found.

“A majority of states” reported that compensation worth one month’s salary is given to police persons annually for their overtime work, as per the BPRD report. This is “hardly an adequate compensation” for a year’s worth of overtime work, it added.

In Assam, Gujarat, Karnataka, Mizoram and Tripura, no system of compensation--monetary or otherwise--was found.

No one we spoke to reported being paid for working overtime, and everyone said a bulk of their salary is spent on rent, as they weren’t able to receive government living-quarters.

Only 29.7% of civil and armed personnel were able to secure official police housing as of 2017, as IndiaSpend reported on October 7, 2019. Further, only three in four of those who had accommodation were satisfied with it. Our field work also showed that existing quarters were unsafe and inadequate.

A constable said his salary improved from Rs 1,200 per month when he joined 25 years ago to Rs 60,000 per month at present. “I don’t save very much,” he said, rather happily, “but my family’s life is well taken care of. At least I don’t need to take a loan to pay for my children’s education.”

A sub-inspector from Ghatkopar was thankful that his family living in the village earned something by farming, to complement his income as a police officer. “Those who don’t have any such support, they won’t save anything by the end of their career,” he said. “Instead of putting in 17 hours a day here, I can do that to set up my own business, so I can earn more.”

Deprived of human rights, labour rights & constitutional rights

Everyone has a right to “just and favourable conditions of work”, Article 23 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights--added to the document by the Indian delegation--proclaims. Further, “rest and leisure”, “limitation of working hours”, and paid “periodic holidays” are a human right, according to Article 24.

As a member of the United Nations who has both signed and ratified the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, India is obligated to uphold the human rights of all its citizens, including its police force.

Similarly, Article 42 of the Indian Constitution mandates the state to provide “just and humane conditions of work”.

The Forty-Hour Week Convention was adopted by the International Labour Organization (ILO) in 1935, mandating that countries provide a forty-hour week to those employed without lowering the prospects of standard of living. To date, India hasn’t ratified this convention.

“Do you think we’re being neutral while judging our lives?” a sub-inspector asked this reporter, while discussing how things have changed in the force, if at all. “Because every two or three days someone like you comes and speaks with us, but nothing ever changes,” he added. “Why don’t things change?”

(Mehta, a second-year undergraduate at the University of Chicago, interned at IndiaSpend.)

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@indiaspend.org. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.