India’s Disconnected Urban Roads Lead To Longer Commutes, Higher Emissions

Mumbai: As Indian cities grow and spread out, poor road planning is creating longer commutes, as per a January 2020 study whose Street-Network Disconnectedness Index (SNDi) shows India’s score to have increased from 3.8 in 1990-99 to 4.3 in 2000-13.

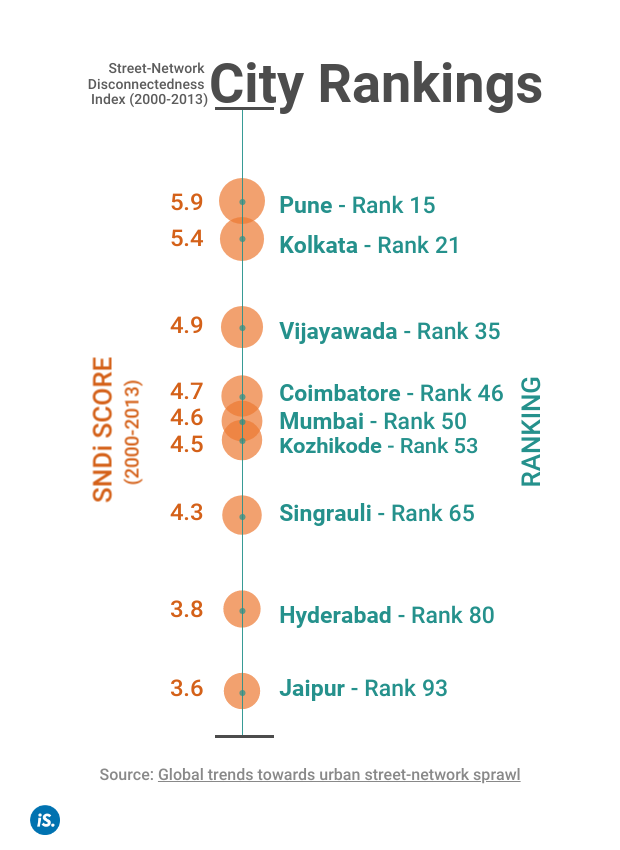

The study puts nine Indian cities among the worst 100 worldwide in terms of street-network connectivity of roads built between 2000 and 2013, with Pune leading the list from India. Mumbai, Hyderabad, Kolkata and Jaipur also feature among them.

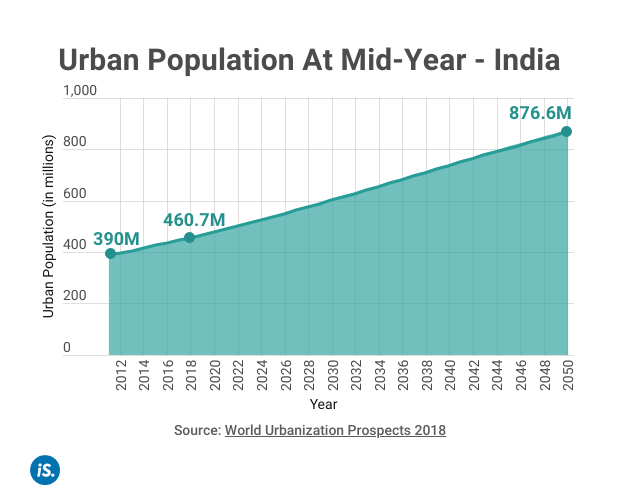

Disconnectedness and longer routes are “strongly associated” with increased vehicle use, previous work by the same researchers shows. This leads to higher CO2 emissions, experts say. The findings are important for India where the number of people who live in urban areas and use these street networks is projected to nearly double between 2018 and 2050.

Today’s choices on the connectivity of streets may restrict future resilience and lock-in pathways of energy use and CO2 emissions for a century or more, the report says.

Trends in street connectivity

The report shows that streets in new developments in 90% of the 134 most populous countries around the world--including India--have become less connected since 1975, while just 29% show an improving trend since 2000. The study was conducted by researchers from McGill University and the University of California, Santa Cruz, USA.

India’s score on the SNDi increased from 3.3 for roads built during 1975-89 to 4.3 for roads built between 2000 and 2013, as per the study, showing greater disconnectedness.

The index also ranked cities for the disconnectedness of their recent road development, and nine Indian cities ranked among the worst 100, as we said. With a score of 5.9, Pune ranked first in India and 15th in the world, followed by Kolkata, Vijayawada, Coimbatore, Mumbai, Kozhikode, Singrauli, Hyderabad and Jaipur.

As the study uses street-network data from OpenStreetMap (OSM), an open source, collaborative project, it may have underestimated connectivity where paths are incompletely recorded in OSM, it says by way of a caveat.

The index

To devise the SNDi, the authors divided up street network into nodes (specific points) and edges (paths connecting the nodes) to measure disconnectedness.

Person A has to take a longer route than person B to travel from start to finish. As per the index, person A’s street network, with fewer connections, more dead-ends, and meandering routes and roads, would present a higher disconnectedness score than person B’s.

Increased emissions

Citing the authors’ research in Europe and North America, their previous study asserts that disconnected street networks are strongly associated with increased vehicle travel, energy use and CO2 emissions.

In India too, road layouts have an impact on vehicle use and CO2 emissions, said Chaitanya Kanuri, urban transport manager with the research organisation WRI India. “Inadequate connectivity between any two locations often results in longer distances that need to be travelled--this directly contributes to more CO2 contributed by the transport sector.”

Networks with low connectivity could also encourage frequent use of personal vehicles over public transport or walking. Examples include street networks with long roads and few intersections as well as roads that extend into internal layouts or gated societies (which link to the main road network at only one point), according to Kanuri.

“These situations result in streets that are not walkable for daily requirements--for going from home to the bus stop, for getting groceries from a nearby store, to meet friends at the local café,” Kanuri explained. “They incentivise personal vehicle use for trips that can be made by more low-carbon transport modes.”

Why India should worry

India must pay attention to this problem as the number of people using its urban street networks is set to balloon in the coming years. India is projected to have the fastest urbanisation between 2018 and 2050 by adding 416 million more urban dwellers, nearly doubling its urban population, according to the World Urbanization Prospects 2018. The country already had the second-largest urban population in the world in 2018 after China, at 461 million urban dwellers.

“Most urban development policies focus on outcomes that relate to urban form: transit, active transport infrastructure, zoning for density, zoning for mixed use, etc.,” said Christopher Barrington-Leigh, co-author of the study. However, if the underlying street network is disconnected, all of these outcomes are constrained.

As a result, despite resource allocation, areas with poorly connected roads are likely to remain underserved by transit and inaccessible by foot, Barrington-Leigh said.

Solutions Box

The study outlined some solutions to prevent the building of low-connectivity developments:

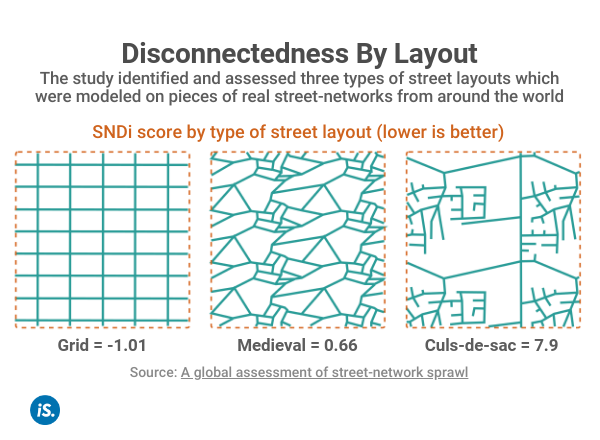

- Policy must require that, where possible, new communities are completely gridded (need not be rectilinear if that is locally not considered aesthetic), given that grids do well according to all the metrics of the index.

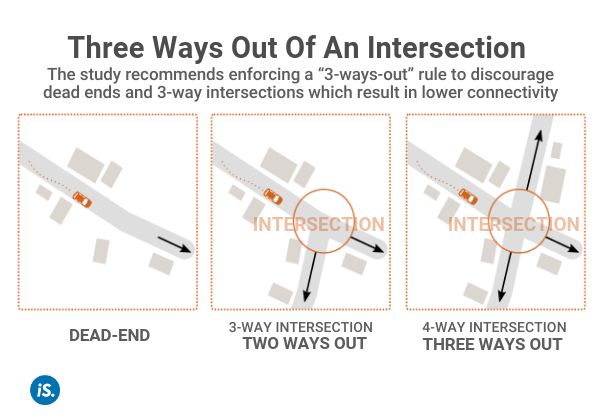

- As an alternative to gridded layouts, introduce a “3-ways-out” rule, which requires that three non-touching routes exist from every new intersection to points outside a new development.

- Discourage or outright prohibit gated communities that cause low walkability and car-dependency.

- Impose a tax on developers for dead-ends and three-way intersections.

(Ahmed is a graduate of architecture from the University of Kent and is an IndiaSpend contributor.)

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@indiaspend.org. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.