India’s Female Voters Not Turning Out To Vote As They Should

Mumbai: Although female voter turnout has been increasing across India--from 51% in 1980 to 66% in 2014--it remains low when compared with the adult population sex ratio in most states.

In the 2014 elections, Madhya Pradesh saw the fewest women voters exercise their ballot relative to their proportion in the state’s population, while Arunachal Pradesh saw more women than men (in relation to the population sex ratio) turn out to vote.

As campaigning for the 2019 general elections gathers steam, female voter turnout trends are important for political parties’ campaigning strategies, as also for the Election Commission of India’s Systematic Voters' Education and Electoral Participation (SVEEP) programme, now nearly a decade old.

Improving women’s participation in voting holds the key to greater voter turnout and socio-political gender parity.

Sex ratio of voters

Sex ratio of voters (SRV) is an important metric to assess gender differences in electoral turnout. Similar to the population sex ratio (PSR), SRV is the number of female voters per 1,000 male voters who actually cast their vote. An SRV of 1,000 will mean the same number of men and women turned up to vote while an SRV below or above 1,000 will mean that more or fewer men than women turned up to vote.

Calculating the sex ratio of voters who came out to vote in the 2014 national election across all 543 parliamentary constituencies in the country revealed that nine out of 10 constituencies with the poorest sex ratio of voters are located in Madhya Pradesh. One might assume that this turnout simply mirrors the underlying PSR (of those over the age of 18 years).

To verify this conjecture, we need the underlying adult PSR for a given constituency. Electoral rolls could have been the best estimate, but recent reports suggest these may not be accurate.

The Census, however, provides this information for all districts in the country. There are 640 districts in India (as per the 2011 Census) vis-a-vis 543 parliamentary constituencies. Roughly, there are a 100-odd more districts than parliamentary constituencies, meaning one constituency might be spread over two districts. In the absence of a one-to-one match between the administrative and electoral data in India, the district-level Census data on adult PSR is the closest approximation of the underlying sex ratio of the adult population in a constituency.

Across all parliamentary constituencies in the country, Bhind has the lowest SRV. If a low SRV is a function of a low PSR, the districts that make up the Bhind constituency (Bhind and Datia) should also have a low PSR. That is not the case, as Table 2, which lists the 15 districts with the worst PSR in the country, shows.

This mismatch between PSR and SRV also occurs at the aggregate state level. The figure below presents the gaps in SRV and PSR in descending order for all states in India.

Source: Census of India, 2011, Election Commission of India, and author’s calculations

Madhya Pradesh, again, has the largest gap (169 women per 1,000 men) between SRV and PSR, followed by Gujarat and Uttar Pradesh. At the other end of the spectrum is Arunachal Pradesh, where the gap is negative--more women than men (in comparison to the PSR) turned out to vote. Both cases suggest that the adult population sex composition alone might not explain the variation in the sex ratio of the voting population.

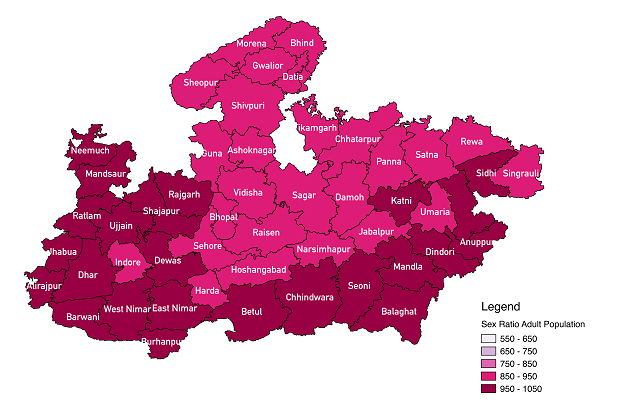

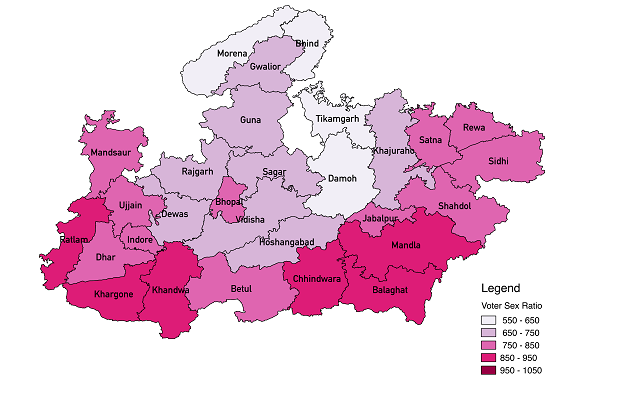

Delving deeper into the intra-state variation using maps enables one to identify spatial trends. Consider the case of Madhya Pradesh again. The state-level SRV is 771 (the lowest in the country), but when broken down by PC, there is huge variation within the state as well (Figure 2 and 3).

Sex Ratio of Adult Population

Source: Election Commission of India

Sex Ratio Of Voters

Source: Election Commission of India

Neemuch and Mandsaur districts have an average PSR of 973. They are subsumed within the Mandsaur parliamentary constituency, which has an SRV of only 813. While this is a gap of about 140 women per 1,000 men, in some cases the gap between the two is much larger.

In Bhind (comprised of Bhind and Datia districts), the gap between the PSR and SRV is over 280 women per 1,000 men. This points to a wide variation within Madhya Pradesh with respect to SRV vis-a-vis PSR. This variation is at the crux of understanding why, independent of the PSR, women in some areas within a state are turning up to vote in larger numbers.

In fact, in Madhya Pradesh itself, the female voter turnout increased from 42% in 1980 to 57% in 2014. Yet, women are voting in smaller numbers than their proportion in the population would warrant. Expectedly, some people--men as well as women--might be left out at the voter registration stage and some more because they do not turn up on election day.

Anything from cultural factors to administrative hiccups like less-inclusive electoral lists could be responsible for this. The Election Commission of India, to its credit, has been making tremendous efforts to improve political participation among women through its SVEEP programme. With more up-to-date electoral lists and massive voter registration and awareness drives under SVEEP, it will be possible to analyse and understand the sex composition of voters in the upcoming elections.

(Kumar is a PhD student in political science at the University of Pennsylvania).

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@indiaspend.org. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.