Modi Win Shows Path To Parliament Is Through 11 States

The venerated mathematician Nassim Taleb popularised the term "Black Swan" to describe an event that occurs outside the realm of normal expectations and has an extreme impact on the present and future. And human nature naively tries to concoct explanations for these events, post facto. The origin of the phrase traces back to a 1697 discovery by a Dutch explorer in Australia of swans that are black in colour, which crushed the prevailing notion that all swans are white. The 2014 Narendra Modi-led Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) victory can be termed India's black swan election.

Here's why. Let's suppose, in June 2013, after Narendra Modi's anointment as BJP's prime ministerial candidate, he announced that the BJP will not contest elections in seven states in the south and east, and instead use his charisma to win 100 per cent of seats in the other states and, thus, propel the party to power. Most of us would have described such a decision as "insanity". Yet, that's almost what happened - the Modi-led National Democratic Alliance (NDA) won a whopping 90 per cent of all seats in the 11 largest "Hindi states" (allowing for a loose description of Hindi states to mean states other than the non-Hindi speaking states of the south and east of India), which sufficed to help the BJP form a government in New Delhi.

The enormity of Modi's electoral achievement in bucking past trends is unfathomable. Through a series of opinion editorials in this newspaper, I had earlier argued, using historical electoral data that India does not vote as one nation ("Debunking the debunked myths", March 20), alliances with regional parties determine national winners ("The math behind Jaylalithaa's PM ambitions", January 6) and that Modi's electoral strategy to nationalise this election was an audacious and a pioneering attempt ("The math of the Modi wave", March 3). In quintessential Modi style, these articles were proved both wrong and right: right that regional parties dominate certain state elections and India does not vote as one nation. Emphatically wrong that regional alliances are the only way to win a national election.

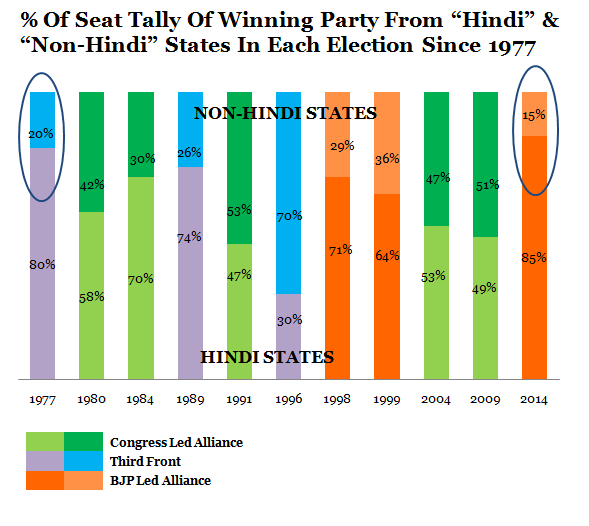

Figure 1

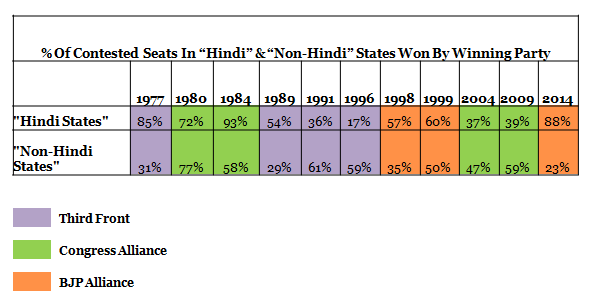

Figure 2

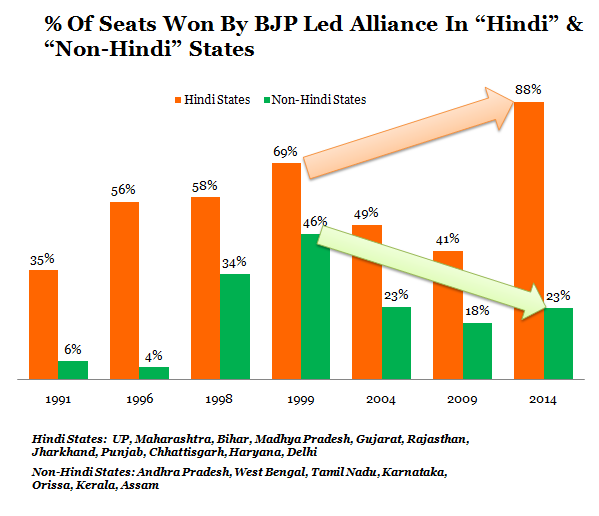

Figure 3

Of the 18 largest states that account for 95 per cent of all seats in the Lok Sabha, seven states can be classified as non-Hindi speaking states in the south and east - Assam, West Bengal, Odisha, the erstwhile united Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka and Kerala. These states account for 40 per cent of all seats and there are dominant regional political parties in six of these seven states. Eleven states - Uttar Pradesh (UP), Bihar, Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat, Rajasthan, Jharkhand, Punjab, Chhattisgarh, Haryana and Delhi, accounting for the remaining 55 per cent of seats are characterised loosely as "Hindi states" for the purposes of this analysis. These states largely featured bipolar contests between the Congress and BJP in most, except UP and Bihar. The BJP's Mission 272 strategy, spurning pre-poll alliances with dominant regional parties and going solo under Modi's leadership was a daring gambit, something no political party had attempted in over 30 years.

And the Modi-led NDA won 85 per cent of its total tally of seats from these "Hindi states". The last time a political party won a general election driven principally by wins in these states was the Janata Party's landslide victory in the 1977 anti-Emergency election, when it won 80 per cent of all its seats from these states. On average, over the last 11 general elections in 40 years, the winning alliance has won 60 per cent of its seats from the Hindi states and 40 per cent from the non-Hindi states. The extent of dominance of the BJP in the Hindi states in this election is unprecedented, as shown in Figure 1.

Further, the Modi-led NDA won nearly 88 per cent of all seats in the "Hindi states" and 23 per cent of all seats in the "non-Hindi" states. This winning percentage gap (65 percentage points) between the Hindi states and the non-Hindi states is the highest in Indian electoral history, reaffirming the "black swan" nature of BJP's electoral performance in the 2014 elections. In six of these 18 states, the BJP alliance won more than 90 per cent of seats and in four states, it won less than 10 per cent of seats. As Figure 2 shows, even during the 1977 election, the Janata Party did not win as high a percentage of seats in the Hindi states as the BJP did in the current 2014 election.

While the BJP-led alliance traditionally has done much better in these Hindi states than in the non-Hindi states in past elections, the 2014 election provided further impetus in this direction. In the non-Hindi states, the BJP alliance performed best in 1999 when it won 46 per cent of seats with the help of regional alliances in Odisha, Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu. Thus, in the absence of these alliances for the 2014 election, conventional wisdom suggested that it would be a Himalayan task for Modi to lead the NDA past the 272 mark. But Modi, true to his reputation, has shattered such conventional thought and proved that a national party can win an absolute majority without needing to win the southern and eastern states through regional alliances.

It is evident that Modi's charm offensive of voters in these "Hindi states" was singularly responsible for the BJP's path-breaking performance in the 2014 elections. Winning 90 per cent of seats in these states is a once-in-a-four-decade phenomenon and for that spectacular achievement alone, Modi should be hailed as a path breaker. This "black swan" victory has understandably piqued the curiosity of many who have sought to explain this victory in sociological terms of "preferences of a new aspirational India", "triumph of development over caste politics", "youth vote for change" and so on. And while vote-share analysis confirms that Modi may have successfully nationalised the election, the difference in seats won by the BJP between these states reaffirms that India still has strong regional voting preferences and concepts of a "youth vote" or a "issue-based vote" are still merely unproven theories. Amid all this, the only thing that is abundantly clear is that when presented with a ballot of choices, the average "Hindi" voter chose differently from the average "non-Hindi" voter, but both agreed that the incumbent needed to be thrown out, which by itself was sufficient to give India its first single-party majority government in 30 years.

(The author is founding trustee, IndiaSpend. This article first appeared in Business Standard)