Mumbai’s ‘M East’: Where 50% Children Under 2 Years Are Stunted, 40% Underweight

Nikhat Mohammed Humayun Sheth, 22, with her sons Mohammed Iman (2.5 years) and Mohammed Ayan (10 months) at Rafi Nagar Slum, Govandi, Mumbai. Mohammed Iman was born premature and was of low birth weight. He suffered from Severe Acute Malnutrition and was often hospitalised.

On the northern edge of the metropolis of Mumbai, lies another face of the city. Buildings give way to hutments, roads get narrower, and government services get scarcer as we reach the ‘M East’ municipal ward, called ‘M/E’ for short.

Known best for housing the 132-hectare Deonar dumping ground that grows by 4,500 tonnes of garbage every day, this ward includes Chembur East, Govandi, Mankhurd and Shivaji Nagar, covering 256-plus slums and 13 resettlement colonies.

This is the ward where 50% of children studying in municipal schools were found malnourished, more than anywhere else in the city, according to data from the civic body, the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC), accessed and published by the non-profit Praja Foundation, as IndiaSpend reported in June 2017.

In this second of our two-part series investigating malnutrition in Mumbai, we visited Govandi to explore how the urban poor face unique challenges; how children, in particular, suffer; and what interventions can help.

M/E ward

A marshy area adjoining the sea, this ward was once considered so inhospitable that the city’s planners intended to use it for refineries, fertiliser plants and an atomic energy plant.

In the 1970s, the municipal corporation resettled many slum dwellers to Shivaji Nagar area from the main city. Later, original residents of the area where the atomic energy plant came up were also resettled here.

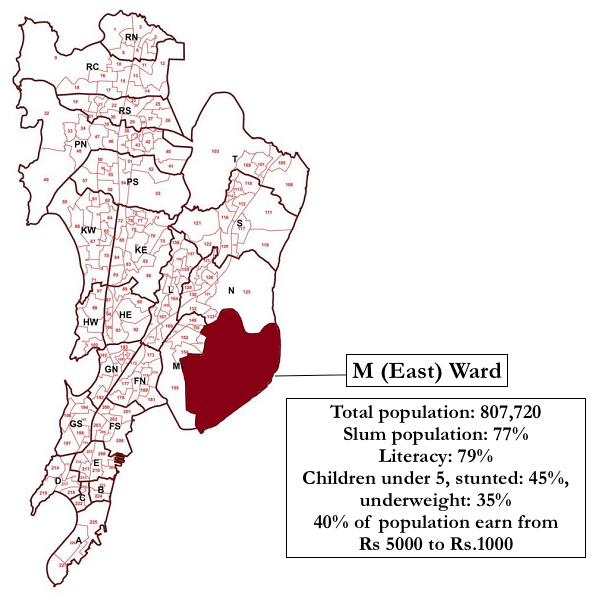

As Mumbai city grew, Bandra’s abattoir and Dharavi’s dumping ground were also moved to this ward. Today, it is home to 800,000 people, 77% of them living in slums. It recorded the lowest human development index in the city at 0.05, worse than many sub-saharan African countries.

Anatomy of a slum

Rafi Nagar is a bustling slum settlement neighbouring the Deonar dumping ground, which looks like a hillock and is as high as four storeys of nearby buildings. A few years ago, the main road was repaired and is now dotted with small shops. On either side are narrow lanes, each with a thin drain running down the middle, on either side of which lie tin huts squeezed together. Each one-room tenement--a kitchen, living space and bedroom rolled in one--faces another. There is little light indoors even during the day, but most houses have electricity and a television set, as well as an open bathing area inside.

Typical slum settlement at Rafi Nagar, Govandi

Each lane is lined with bright blue cans placed outside each house, so as to make a quick dash when the water tanker arrives. Household activities are planned around the arrival of the tanker.

Left to right: An abandoned toilet complex at Lotus Colony, Govandi, Mumbai; bright blue cans are placed outside each house, so as to make a quick dash when the water tanker arrives.

Water is rationed, so bathing is not a priority. Public toilets are in a poor shape and most seem to have been abandoned due to lack of maintenance.

In 2011, families in Mumbai slums spent between 52 times and 206 times more on water than the standard municipal charge, and 95% of slum-dwelling families used less water than the World Health Organization’s (WHO’s) standard of 50 litres per person, according to this study published in the journal BMC Public Health.

Without safe drinking water and adequate sanitation, children often contract diarrhoea, the second-most common cause of death in children under five.

Meagre incomes, little food to go around

In the holy month of Ramazan and most women were sitting outside their homes embroidering skull caps. Younger children were tasked with sorting the beads or gluing them together.

Left to right: During the month of Ramazan, most of the households in the slum are working on embroidering skull caps, children also help out; children swim in the creek to beat the heat oblivious to the fact that drains open into the creek at Rafi Nagar, Govandi

Some children beat the muggy May heat by playing in the creek, into which dirty drain water empties out.

In one of the numerous crowded lanes of Rafi Nagar, we met 10-year-old Sadia Khan and her family. Sadia looked no older than eight, and studied in grade VI. Her mother, Nazbunissa Khan, 30, said Sadia was often sick with diarrhoea and complained of weakness.

Sadia Khan, 10 and her brother Mohammed, 8, living in Rafi Nagar, Govandi are malnourished. Sadia doesn't like to eat vegetables and fruits and her family cannot afford milk. Her brother says he doesn't like the khichdi served for mid-day meal in school.

Like many children her age, Sadia did not care for fruits and vegetables but preferred snacks such as lahsun chivda (garlic-flavoured fried chickpea flour mix), “Chinese bhel” (made from noodles and schezwan sauce), aloo bhujia, Khan said.

Khan has three children, and previously lost two to tetanus and tuberculosis. She has no education and hails from Uttar Pradesh. Her husband, a zari worker (an embroiderer), is the only earning member.

Sadia’s family was typical of most families in M/E Ward. As many as 40% of the families here earned between Rs 5,000 and Rs 10,000 a month, 20% earned less than Rs 2,000, and, in all, 62% were not able to save anything, according to a 2015 study conducted by the Tata Institute of Social Studies (TISS), Govandi, and covered all households in the ward.

With such meagre earnings, 59% of the families could only afford two meals a day. Fewer than 10% were able to consume items such as milk, fish, meat, eggs and fruit on a daily basis. Most families bought milk but used it only for tea.

Low income had a direct impact on the quality and quantity of food available, and the results were dire: 45% of children under five in M/E ward were stunted and 35% were underweight. Nearly half the children under two were stunted and two-fifths underweight, as per the TISS study.

The illiteracy rate in the ward was 21%, twice that of Mumbai’s (11%); 30% of women here were illiterate, which was thrice the 9% rate among Mumbai’s women; and 90% of Muslim women living in the area did not work for a living.

On most days, Sadia’s family did not have enough to buy milk and the children do not carry tiffin (packed lunch) to school. When asked if her daughter ate the mid-day meal offered in municipal schools, Khan said she did not know.

“We don’t like the khichdi served,” said Sadia’s younger brother Mohammed, 8, who was also thin and frail.

Khan said the children ate a meal of rice and dal (curried lentils) on coming home from school.

Large families, more mouths to feed

Family planning is not a popular idea here due to religious and cultural inclinations and, often, women’s lack of decision-making power.

When asked if she had tried family planning, Khan said no: “I want to have five kids, maybe one more boy.”

Most women in M/E ward undergo 3.8 live births on average, of which 3.6 survive.

Education significantly impacted family size, and women with more than secondary education reported half the birth rate compared with women with no education, the TISS report noted.

“We have visited households where a mother has had 17 children. Our field officers have to work very hard convincing them about seeking family planning methods,” Sonali Patil, Associate Program Director with the Society for Nutrition, Education and Health Action (SNEHA) Centres, which works to curb malnutrition in children and promotes contraception among women, told IndiaSpend.

Sonali Patil, Associate Program Director, Society for Nutrition, Education and Health Action (SNEHA) Centres Program which is working on malnutrition in children and anemia and contraception in reproductive women in the area.

Patil said 66% of women did not practice family planning when SNEHA carried out a baseline study in 2011 among 6,000 women in the reproductive age group in Govandi and Mankhurd. She said the figure had decreased to 59% in 2016, after SNEHA’s intervention.

Lack of education also posed a challenge to government-run immunisation programmes.

“It is not easy here, we organize immunisation camps but no one turns up,” a medical health officer who did not wish to be named, told IndiaSpend. “We have to spend an hour speaking to a mother to convince her to let her children get immunised.”

We visited Nikhat Mohammed Humayun Sheth in her Rafi Nagar house. Sheth looked barely 16 years old, but said she was 22. Her two-and-half-years-old toddler was playing outside and there was an infant rocking in an improvised hammock suspended from the ceiling.

Her older son, Mohammed Iman, crawled inside and started asking for his “powder”, a medical nutrition treatment (MNT) supplement made and distributed free-of-cost by the Nutrition Rehabilitation Centre in Dharavi.

Mohammed Iman was born premature at eight months, weighing only 1.7 kg. He was confined to an incubator during his first few days, and had constant health issues since, including jaundice and diarrhoea for which he had been hospitalised.

Baby brother Mohammed Ayan is 10-months-old, was born at full term and weighed 2.4 kg at birth. However, he was also admitted in Sion Hospital recently for pneumonia.

A baby weighing less than 2.5 kg at birth is termed ‘low birth weight’ irrespective of gestational age, according to the WHO. Both Mohammed Iman and Ayan were low birth weight babies.

Low birth weight infants are 40 times more likely to die within first four weeks of life than normal birth weight infants. Low birth weight is also linked to inhibited growth and cognitive development as well as chronic diseases later in life.

Nikhat said she is determined to keep her children healthy but struggled to manage expenses with the Rs 5,000 a month that her husband, a zari worker, earned.

Limited access to basic services

Many among the most vulnerable are unable to access government services.

The area has four health posts--primary health care centres that provide maternal and child care services--for a population of over 500,000, Sanjay Bamne, Deputy Programme Manager with the non-profit Apnalaya told us in his office in Shivaji Nagar. There are 21 anganwadis (creches) for a population of 42,000.

Bamne said it has taken years of advocacy to get health posts and anganwadis here. “The anganwadi workers do not use electronic weighing scales and measure only weight and not height, so they only measure whether a child is underweight and not stunting and wasting,” he said.

Non-profits such as Apnalaya have evolved their strategies from providing nutritional supplements to malnourished children to encouraging health-seeking behaviour among mothers and counselling them about nutrition.

“We help mothers create groups, which encourage members to deliver babies in hospitals, take their children for immunisation, and so on,” said Jagdevi Bansode, a field officer with Apnalaya who has been working here since the last 24 years, and now oversees four health workers. “We have been conducting cooking classes, giving women ideas on how to cook wholesome, nutritious meals for their children.”

Jagdevi Bansode, field officer, Apnalaya, has been working in this slum for the last 24 years.

Since 2010, the Nutrition Rehabilitation Centre at the Urban Health Centre in Dharavi, known as ‘Chhota Sion Hospital’, has been treating malnutrition in urban areas in and around Mumbai.

Its nutritionists, doctors, nurses and counsellors as well as an in-patient facility attract malnourished children from as far as Thane (30 km away) and Palghar (100 km away).

It is here that the WHO-recommended MNT powder is made from peanut butter, soya, milk powder, powdered sugar and micronutrients. It is distributed for free to children with severe acute malnutrition (SAM).

“Children with severe acute malnutrition (SAM) are nine times more likely to die and those with moderate acute malnutrition (MAM) four times more likely to die of any causes than normal children,” Alka Jadhav, department head of paediatrics at Lokmanya Tilak Municipal General Hospital, Sion, who oversees the rehabilitation centre, told IndiaSpend.

The MNT powder is designed to encourage rapid weight gain. It takes six to eight months for an SAM child to reach the MAM stage. The centre has treated over 3,000 malnourished children so far.

Jadhav said it was more difficult to treat malnutrition in urban areas than in rural areas: “Living expenses in cities are far more and with changing aspirations like wanting cable TV and mobile phones, nutrition is just not a priority for most households.”

(Series concluded. You can read the first part here.)

(Yadavar is principal correspondent with IndiaSpend.)

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@indiaspend.org. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.

__________________________________________________________________

“Liked this story? Indiaspend.org is a non-profit, and we depend on readers like you to drive our public-interest journalism efforts. Donate Rs 500; Rs 1,000, Rs 2,000.”