Can Treated Wastewater Help Meet India’s Increasing Water Needs?

While India’s water resources dwindle and demand rises, sewage generation is on the rise. Treating this wastewater could help India mitigate water stress

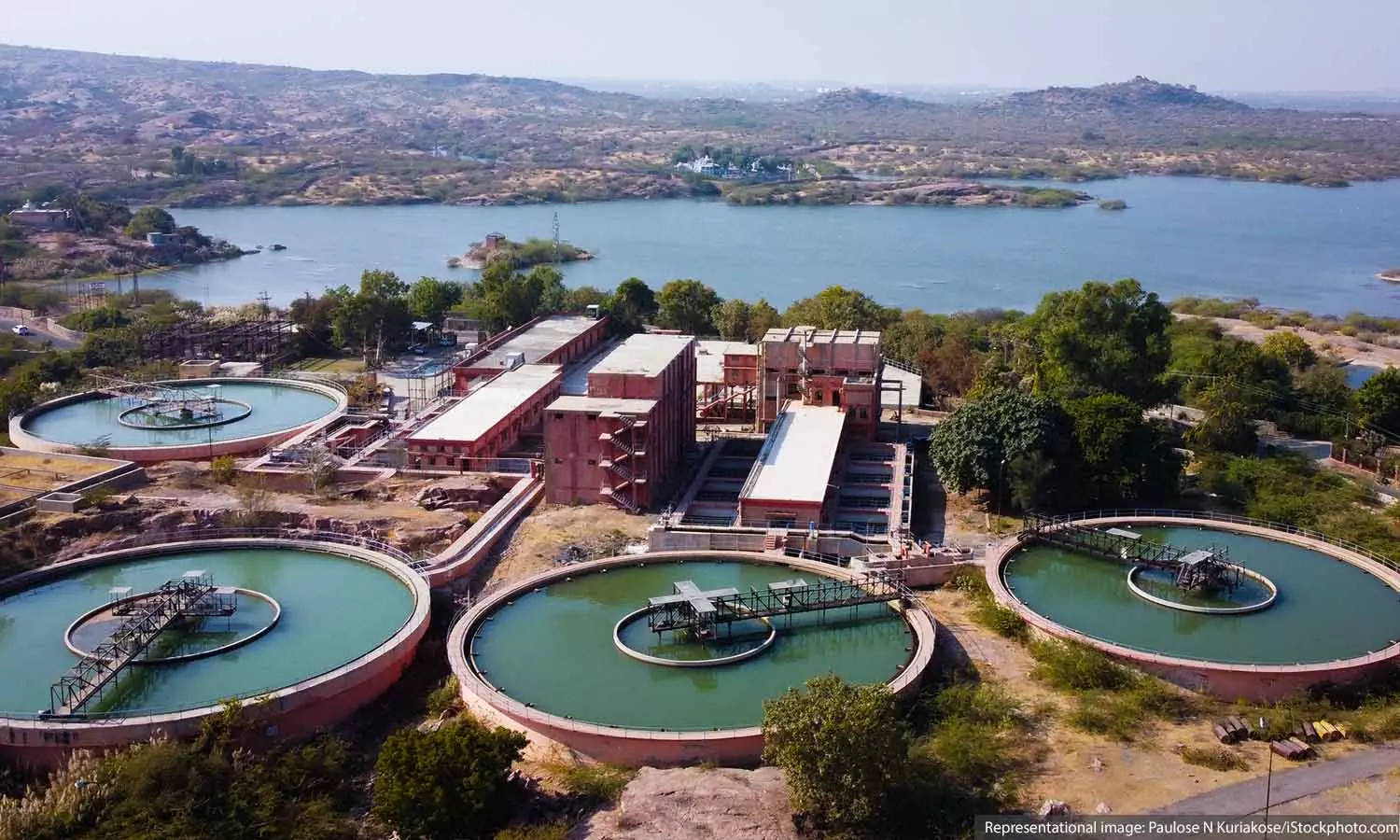

A water treatment plant in Jodhpur, Rajasthan

Chennai: When Chennai resident Anand Raj and his two siblings decided to construct a three-storeyed home, with an apartment per floor for each sibling, some of their decisions centred around water.

For one, their plot is in the outskirts of the city, with no municipal water and sewage connection. Having experienced water scarcity and flooding in equal measure, they wanted to be better prepared. It was during the planning that they read about water allocation for everyday activities.

The Bureau of Indian Standard (BIS) BIS 1172: 1993 specifies the requirements for water supply, drainage and sanitation. It mentions 150 to 200 litres per head per day (lpd) for communities with more than 100,000 population, which may be reduced to 135 lpd for houses of lower income group residents. However, the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs has fixed 135 lpd as the benchmark for urban water supply.

The standard of 135 lpd is however only for the domestic needs, such as drinking and bathing, and the non-domestic need of flushing. There are other needs, such as for agriculture--which consumes the maximum at 91%; this means that the total per capita annual water need is more.

With rising population, increasing urbanisation and rapid depletion of surface and groundwater sources, India is faced with a grim future. And while the country aims to improve recharge, there is another factor that could help increase availability of water for certain activities: treated wastewater. This is not new, nor is it limited to India. At COP29, delegates were offered cans of beer from Singapore, made with treated sewage.

The challenge, however, is that only two states have more sewage treatment capacity than the quantity they generate. And most plants do not operate at optimum efficiency, which means only about a quarter of the wastewater generated gets treated for re-use.

Shrinking water availability

With increasing water needs, many districts are moving towards water scarce conditions.

The annual per capita water availability is calculated by dividing the annual average water availability by the population.

India’s per capita water availability has decreased from 1,816 cubic metre in 2001 to 1,486 cubic metre in 2021. It is estimated to drop further to 1,367 cubic metre by 2031 and 1,219 cubic metre by the year 2050. Increasing population, urbanisation and changing rainfall patterns are cited as the main reasons for shrinking water availability.

When the per capita availability is between 1,000 and 1,700 cubic metre it is considered stress; between 500 and 1,000 cubic metre, it’s considered scarcity. When it goes below 500 cubic metre, it is considered “absolute scarcity”. A majority of the districts in India are water-scarce as of 2025 and a few districts in Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, and Tamil Nadu are already in the absolute scarcity category, as per the India Climate and Energy Dashboard (ICED).

Districts such as Gujarat’s Surat, Dhule, Jalgaon and Nandurbar in Maharashtra’s Khandesh region and Amravati, Akola and Buldhana in Vidarbha are projected to move from stress to scarcity by 2050. Kodagu, Ramanagara and Mandya in Karnataka, and Wayanad in Kerala are projected to move from scarcity to absolute scarcity. Tamil Nadu fares poorly, with 17 districts projected to move from scarcity to absolute scarcity, making the per capita availability of water less than 500 cubic metre across the entire state except in two districts.

Given the depleting freshwater resources, there arises the question of how India’s water needs could be met.

Freshwater down the drain?

Of the 135 lpd norm, 45 lpd is considered necessary for flushing toilets.

“I never gave it a thought before,” says Anand Raj. “We get piped water supply in Chennai. We’re literally flushing treated freshwater down the drain.” A few like him consider this a waste of freshwater and of the money spent on treatment.

But S. Vishwanath, a Bengaluru-based water professional with nearly three decades of experience, begs to differ. “It was 45 litres when we had those huge cisterns that used chains to flush 20 litres of water. Now we have flush-efficient tanks that use only three and six litres of water,” he says.

“It’s interesting how this narrative of pouring treated water down a toilet has been built up. The cost of treatment is the least in a water supply system. The cost is mostly in pumping and piping,” Vishwanath clarifies. “Increased water consumption, especially in urban areas, is more on dishwashing and washing clothes, the major consumer now.”

Polluting the water bodies

The other seemingly unrelated but important facet is the pollution of water bodies, experts in the water sector point out.

The domestic wastewater that urban India produces is 72,368 million litres per day (mld), as per the 2021 data of the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB); rural India generates 39,604 mld of wastewater. Except Chandigarh and Haryana, the capacity of sewage treatment plants (STPs) in the other states is far less than the sewage generated. Besides, the STPs do not function at maximum capacity as per CPCB’s draft guidelines for use of treated sewage, circulated in February 2024.

Thus, about 28% of the sewage generated is treated while the rest is let out untreated. On top of that, what is treated does not conform to the prescribed environmental norms.

Pointing out that 311 stretches of 279 rivers were polluted as per a CPCB 2022 study, Nitin Bassi, senior programme lead at the Delhi-based think-tank Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW), says in an email that releasing untreated wastewater into freshwater bodies has adverse impacts on the environment and public health. “It pollutes water bodies, diminishes their ecological functions and impacts the water quality, especially for communities downstream,” he says.

CPCB has designated water quality criteria based on usage. As per the 2023 water quality data, the faecal coliform of River Ganga at Gangotri was the most probable number (MPN) of 2 per 100 ml--the maximum limit being 2,500 MPN/100 ml. About 250 km downstream, at Rishikesh, the maximum count was 48 MPN/100 ml. About 700 km further down, it reached 490,000 MPN/100 ml at Sultanpur.

The biological oxygen demand--the measure of oxygen that microorganisms and bacteria consume to cause decay of organic matter--remained within the limit of 3 mg/l in the initial stretches of the Ganga, but reached 11.6 mg/l at Kanpur. Similar numbers for other parameters, including dissolved oxygen and total coliforms, for other rivers, lakes and tanks underline the extent of pollution.

About 70% of our surface water is contaminated, as per a 2019 NITI Aayog report.

“Consuming contaminated freshwater without proper treatment can result in outbreaks of waterborne diseases like cholera, tuberculosis, dysentery and diarrhoea--a major cause of stomach ailments in India,” says Bassi of CEEW.

The National Framework on Safe Reuse of Treated Water advocates reuse of treated water to address the problems of scarce freshwater resources, environmental pollution and public health risks, and envisions a sustainable circular economy approach.

Relieving water stress with treated wastewater

In 2008, India’s water supply was slightly more than demand at 650 vs 634 billion cubic metres (bcm). In the next five years, the demand is expected to be double the supply (1,498 vs 744 bcm supply).

Eleven out of the 15 major river basins will experience water stress by 2025, as per a 2023 CEEW analysis. Climate change is expected to exacerbate the crisis.

Water scarcity impacts about 60% of major industries, as per a guide titled Circular Economy Pathways for Municipal Wastewater Management in India: A Practitioner’s Guide. Though industries use only 8% of the total water consumption, they use 2–3.5 times more water for production, compared to similar industries in other countries.

Thermal power plants use 3.5-4 cubic metre of water per hour per megawatt for cooling and other purposes. In the 2013-16 period, 14 of India’s 20 large thermal plants faced shutdown at least once because of water shortage.

In sum, most of the country's economic activities would be affected by water stress.

While the government has been advocating rainwater harvesting and water conservation measures in agricultural and industrial sectors, experts say it is time to focus more on the reuse of wastewater.

Reusing treated (municipal) wastewater would help reduce water stress, according to Nitin Bassi. “It would address the supply-demand gap and provide an alternative source for meeting water demand for non-potable purposes such as cooling, road cleaning, irrigation of horticulture crops, spraying in mine pits, boiler feed, processing, toilet flushing,” he says.

He points out that national and state policies--like that of Haryana for instance--recommend the use of treated wastewater for construction activities, citing the example of cities such as Pune, Nashik and Thane that are practising it.

“Industrial wastewater has a different quality. It’s treated in effluent treatment plants. Restaurant wastewater is a trade effluent and has to be treated separately. In commercial buildings and apartments, we can treat greywater--wastewater from kitchens, bathrooms and washing machines, and blackwater--the water from toilets that contain faecal matter, in the same STP without segregating,” explains S. Vinoth, director at Espure Water Solutions Pvt Ltd, a company that works across the southern states.

To the question of whether the government should supply treated wastewater for flushing and gardening, experts say that it would entail a parallel system to supply treated wastewater, and hence entail a huge financial outlay.

“As is happening now, where apartments have sewage treatment plants, freshwater can be replaced by treated wastewater for flushing and gardening,” says Vishwanath, the water expert.

A. Gilbert of Aims Water Management which operates across the south, says that many apartments in Chennai use treated wastewater for flushing. Though the city’s planning authority mandates STPs under certain conditions, some eco-conscious builders provide STPs, according to him.

Vinoth sees conservation of freshwater, and prevention of surface and groundwater pollution as the main advantages of using treated sewage water.

It is estimated that Rs 20 lakh crore investment is required to bridge the demand-supply gap of water by 2030, as per the 2019 NITI Aayog report.

“Residents in apartments may not see STPs as financially beneficial--for a 20-house apartment of four-member families, it would cost Rs 10 lakh to install and Rs 40-45,000 per month to operate,” says Vinoth. “Also, often the extra treated wastewater is let out into the drains. The sludge can be used as manure or to produce biogas.”

“But for a bank or an IT company with a lot of backend operations, treated wastewater can be used for cooling purposes,” he says. He cites the example of a multi-storeyed building where 200 kilolitres (kl, where 1 kl is 1,000 litres) of wastewater is treated in their STP every day. “The entire treated wastewater is used within the premises for cooling and for flushing toilets. They save money on groundwater extraction or on the treated water they would otherwise have to buy.”

Industries also use treated (non-effluent) municipal sewage, primarily for cooling purposes. Generally the process involves primary, secondary and tertiary treatment. The tertiary treatment varies as per the water quality norms required for a particular operation, say experts.

Chennai Metropolitan Water Supply and Sewerage Board (CMWSSB) supplies treated sewage after tertiary treatment to a few industries in the outskirts of the city. If necessary, the industries treat the water further as per their required norms. One private power plant bought raw sewage from CMWSSB and carried out its own treatment as long as the plant was in operation.

Maharashtra State Power Generation Company uses treated wastewater from Nagpur for its thermal power plants in the region. It saves Rs 6.2/m3 by using treated wastewater, while reducing freshwater extraction by 47 m3/year.

The 2012 National Water Policy encourages reuse of urban wastewater.

The Union government set up the Bureau of Water Use Efficiency (BWUE) in 2022, and one of BWUE’s mandates is water recycle and reuse.

“The draft Liquid Waste Management Rules, 2024, identifies residential and commercial establishments using more than 5,000 litres of water per day as bulk water users, and they must treat the wastewater generated under extended user responsibility,” says Bassi of CEEW.

Experts point out the importance of such mandates being fully implemented so that India’s water stress can be mitigated. IndiaSpend reached out to a senior official at the CMWSSB for details on the treated wastewater being supplied to industries. We will update this story when we receive a response.

An analysis of Central Water Commission’s 2021 basin water availability by CEEW lists the economic benefits of using treated wastewater, saving millions of rupees. For instance, 8,603 million cubic metre of treated wastewater could have been used for irrigating 1.38 million hectares, preventing the same volume of freshwater withdrawal. It would have produced 6,000 tonnes of nutrients, thus avoiding fertilisers.

“But people’s mindset about wastewater reuse has to change. Then we can truly reap such benefits,” says Vinoth of Espure.

As for Anand Raj and his siblings, they are still weighing their options on the small domestic sewage plant technologies available on the market. They hope to do their bit to conserve freshwater by using their treated sewage to the maximum extent possible.

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@indiaspend.org. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.