Taking Over Fertile Land For Adani Group From Protesting Farmers, Jharkhand Government Manipulates New Law Meant To Protect Them

Santal Adivasi farmers fall at the feet on Adani personnel on August 31, 2018, begging the company to not take their land. Credit: Abhijeet Tanmay/Kashish News

Godda, Jharkhand: Soon after police personnel drove up in a convoy of vehicles that Friday, August 31, 2018, “Adani ke log (Adani’s people)” arrived with earthmoving equipment, recounted Adivasi (tribal) and Dalit villagers in Mali, in this lush eastern corner of Jharkhand.

“There were eight to 10 police for each of us villagers,” said Sita Murmu, a wiry farmer in her 40s from the Santal community, one of India’s largest indigenous tribes, describing the attempt that followed to take over the villagers’ farmlands, abutting a clutch of mud and brick homes.

These fertile, multi-crop lands are their only source of livelihood, and the villagers were shocked when the earthmovers began uprooting valuable palm trees and bulldozing the young paddy stalks, laboriously sown weeks ago.

“We begged Adani’s people to stop,” said Santali farmer Anil Hembrom. “But they said our land was theirs now, that the government had given it to them.”

Villagers said they made urgent phone calls for help to Godda’s deputy commissioner (DC) and the superintendent of police (SP). “The SP told us, ‘Go to the local thaana (police station) and lodge a complaint,’” they recalled. “We told him, ‘how can we lodge a complaint at the thaana, when the police from there are here with Adani.’” The DC too ignored their pleas, villagers said, recalling, “She said, ‘Your money (compensation for the land) is lying in the government office. Go, take it.’”

Meanwhile, Adani personnel were casting concertina wire to fence off the land, and a farm pond. Santalis bury their dead on their land, and the earthmovers dug up this clan’s burial site too, the farmers recalled.

Witnessing the destruction, women farmers fell at the feet of Adani’s personnel, pleading with them to spare their land. They wept as they said they could not survive without it.

Onlookers filmed these scenes on their cellphones, and the story was picked up by a Godda-based Hindi news outlet but found no mention in India’s legacy media. Alarmed by the women’s protests, the Adani team and the police eventually aborted the land acquisition attempt that day.

IndiaSpend sent questionnaires to the Adani Group and Godda DC Kiran Pasi on the morning of November 20, 2018, about the incident in Mali and the broader land- acquisition project. Neither replied. If they do, we will update this story with their responses.

The villagers’ battle against the Adani Group began in 2016, when Mali, 380 km east of state capital Ranchi, and nine other villages around it became contested territory. That was when Adani Power (Jharkhand) Limited, a subsidiary of the Adani Group, told Jharkhand’s BJP-ruled government that it wanted to build a coal-fired plant on over 2,000 acres of land—private farms and commons—in these villages, according to official documents reviewed by IndiaSpend.

The Adani Group is led by Gautam Adani, one of India’s richest and most powerful tycoons. Its proposed 1,600 megawatt (MW) plant in Godda is to be fuelled with Australian and Indonesian coal imports. When complete—the commissioning year is 2022—it will sell all the electricity via high-tension lines to Bangladesh. The proposal for the plant came in August 2015, following a visit by Prime Minister Narendra Modi to Bangladesh. Adani was among the industrialists accompanying Modi, and the agenda featured power transmission.

But forcible takeover of land for the plant—as several farmers in Mali, and surrounding villages like Motia, Nayabad and Gangta are experiencing—was meant to be relegated to the past with the Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act (the LARR Act). Parliament passed the LARR Act in September 2013 unanimously, an acknowledgement that the 1894 Land Acquisition Act , in force for 123 years, needed to be scrapped.

Forcible state takeover of land and private property for infrastructure and development is a legacy of British India, legitimised by the 1894 law. In post-independent India, this colonial-era law was particularly criticised for being abused by governments to take over private rural land for industry, sparking numerous bloody battles over land, from Kalinganagar to Nandigram. The brunt of this eminent domain—the power of the state to take over private property, citing public purpose—was disproportionately borne by Adivasis. Among India’s most disadvantaged communities, they make up 8% of India’s population, but an estimated 40% of those dispossessed for dams, mines and industrial projects.

The LARR Act provides “additional safeguards for them, such as informed consent to acquisition of their land,” said Muhammad Khan, a lawyer, and Congress party spokesperson who had helped draft the act, and also co-authored ‘Legislating for Justice’, a book on the issue. “The Act also provides for additional compensatory measures of land-for-land for Scheduled Castes (Dalits) and Scheduled Tribes (Adivasis),” he said. “This was an important safeguard, a recognition that the identities and livelihoods of such communities are strongly grounded in land.”

But the Jharkhand government’s use of the LARR Act, we found, demonstrates how a relatively progressive law can end up replicating the colonial predecessor it was meant to negate. This case holds important lessons for Jharkhand, and the rest of India, because it marks the first time the state government has evoked the LARR law for private industry.

In Mali and surrounding villages, IndiaSpend found that the LARR Act’s aim of making land acquisition a “humane, transparent, participative and informed” process has been compromised.

For government institutions, long accustomed to deploying eminent domain powers with little public accountability, key safeguards introduced by the LARR Act—related to social impact assessment, “public purpose” justification, free prior, informed consent of affected families, land-for-land compensation for Adivasis and Dalits, and transparency and participation in decision-making, have been either undermined, or bypassed.

In a brief conversation with us on 19 November, 2018, Godda DC Pasi defended the acquisition.

“Farmers want the plant on their land,” she said, referring to the government’s acquisition of nearly 500 acres of land in four villages over this year. Asked about protests, in particular by Adivasi and Dalit farmers, she asked us to send her a questionnaire. IndiaSpend did so on 20 November, 2018, but Pasi did not respond, despite two reminders over two days.

How a ‘humane, transparent, participative’ law is flouted

Backed by the government, Adani personnel are taking over and fencing off private land and village commons. They are destroying multi-crop farm land, which provides year-round work and livelihood to its owners, sharecroppers and farm labour (right).

On August 31, 2018, Mali’s Santali farmers, such as Talamai Murmu, fell at the feet of Adani personnel, begging them to not acquire their land. “They just took it over like dacoits,” said Gangta villager Ramesh Besra (right), whose land is now in the company’s possession.

When IndiaSpend first visited Mali’s farmers weeks after the violent acquisition attempt of August 31, 2018, their lands had still not been taken over. But villagers were tense about the possible return of Adani personnel and police. Manager Hembrom, one of the landowners, said if that happened, they would “vehemently protest.”

“Land is everything for us,” Hembrom said of the fertile farms, where villagers grow rice, wheat, maize, pulses and vegetables around the year. “Our livelihood, our life, the basis of our identification for every benefit from the state.” Sita Murmu and other women farmers agreed: “We labour on our own land, and sustain ourselves. There is no way we will give it up.”

The villagers were looking at serious economic losses and food insecurity, given Adani personnel had destroyed their standing rice crop, and there would be no paddy to harvest in coming weeks.

“With our crop destroyed, we will also struggle through this coming year to get enough (fodder) to feed our livestock,” said Hembrom. Murmu has filed a case in the district court under the Prevention of Atrocities Act against the Adani personnel who destroyed her crop on August 31, 2018. They would have to wait until November to sow the next crop of wheat, said the villagers. On 23 November 2018, farmers told us this crop too was in question: eight days earlier, Adani personnel sent a complaint to the Godda police asking them to stop Hembrom and others from growing a new crop on their land. The company said the government had acquired this land for them.

As the villagers were speaking to IndiaSpend, Bimal Yadav, an aged sharecropper among them, started to weep. “Adani babu, please leave our land,” he pleaded. “We might get by on the money you are giving us for it, but what will our future generations live on? We beg you, please do not take our land.”

The following day, walking through the uprooted trees and damaged crop on her land, Lakhimai Murmu, one of the villagers also broke down. “When we have not agreed to give our land, how can they forcibly take it?” she said. “Why don’t they just kill us first?” She surveyed the field, pointing to small surviving paddy patches here and there, and told her family, “Maybe we can retrieve a little bit of dhaan (rice).”

Villagers in this section of Mali still hold out hope that the government might heed their protests. But Adivasi farmers in the neighbouring villages of Gangta and Nayabad like Suryanarayan Hembrom and Ramesh Besra, have seen their ancestral lands seized in recent months for the plant. “They just took it over like dacoits,” said Ramesh Besra of his farmland in Nayabad. “We could not do anything.”

Hembrom said that in the second week of July, 2018, a day after he had sown his fields, Adani personnel arrived in Gangta with police and began cordoning off land and moving in earthmovers. Hembrom’s farm was among those destroyed. When he tried to protest on his land the following day, joined by other villagers, Adani personnel and officials arrived and tried to evict them, he said.

“‘On which authority’s orders have you come here,’ they asked me,” Hembrom recalled. “We told them, ‘This is our ancestral land. We survive on farming. Should we ask the government for permission to come on our own land?’”

Marynisha Hansdak, a Godda-based Santali reporter, who was with the farmers that day, had been reporting Hembrom’s story. Adani officials who arrived on the scene threatened her to delete her footage, including visuals of them on the contested land, she said.

“I told them I was doing my job of reporting the story and would not delete my footage,” Hansdak said. Adani personnel, she said, responded by summoning the police. Hansdak left with the villagers from the area and took refuge in one of the villages for the night.

Within days, a court notice landed at Hembrom’s house, informing him that the police had admitted an FIR by Adani staff, who charged five Adivasi villagers including him with rioting, criminal trespassing, and breaking public peace. Hembrom is currently out on bail. An Adani spokesperson did not respond to questions by IndiaSpend on the cases filed by the company against the farmers.

Godda MLA Pradeep Yadav, who has raised questions since 2016 about the project, spent five months over 2017 in prison on similar charges and is currently on bail. “I was questioning the government’s and Adani’s outrageous mili-bhagat (connivance) to profit the company,” Yadav alleged. “So, the police slapped numerous cases on me. Sending their elected representative to prison was a clear message to the villagers to live in fear.”

Suryanarayan Hembrom and other farmers are facing criminal cases for resisting the acquisition of their land.

On a recent morning, a large group of villagers gathered in Mali-Gangta, to speak about the terror they felt. “We have no peace since the company has come,” said a Santali farmer Mohan Murmu. “They have taken away the grazing lands of our livestock too.” Those who spoke up in solidarity were not spared either, others in the group said. Adani group personnel threatened them, they said, telling them to not join protests, else their land would be taken too.

Both Besra and Hembrom have refused to accept monetary compensation, on the ground that they never agreed to give their land to the Adani Group. The same is true for farmers Balesh Kumar Pandit, Chintamani Shah, Ramjeevan Paswan, and Jayanarayan Shah from nearby villages. A retired schoolteacher, Chintamani Shah has filed numerous complaints since December 2016, listing violations in the land acquisition process.

“When I have been opposing losing my land to Adani since Day 1, and I continue to do so, on what moral grounds can I take that money?” Chintamani Shah asked, referring to the 42 lakh rupees compensation, which he has refused to take, after the government acquired his land in May.

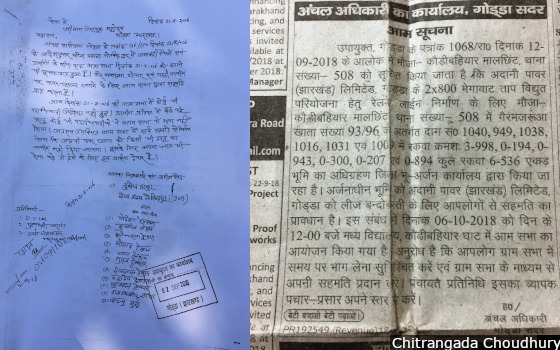

Several villagers brought out letters, appeals and gram sabha (village assembly) resolutions made between 2016 and 2018 stating their opposition to the land acquisition. These were addressed to a number of authorities—from officials in the district to those in the state capital of Ranchi, to the Jharkhand governor Draupadi Murmu.

The governor has a special role under the Constitution, with regard to scheduled tribes, in particular, in preventing the alienation of land. Governor Murmu’s office did not respond to an IndiaSpend questionnaire about action taken by her office on these complaints.

“Kisise koi sunwaai nahi hai (there is no hearing for us from any quarter),” was a refrain we heard over and over again in the 4 villages witnessing acquisition.

Public Purpose: Farmland for Adani, electricity for Bangladesh

When the LARR Act came to be, India’s minister for rural development, Jairam Ramesh, had argued that the state should rarely invoke the power of eminent domain granted by the law, and instead, opt for the market mechanism. This principle especially applied to land acquisition for private corporations, he argued.

“You want land? Go buy the land,” Ramesh had said, addressing industry at that time.

For its proposed power plant in Godda, however, as per documents reviewed by IndiaSpend, the Adani Group wrote to the Jharkhand state government on May 6, 2016 and August 2, 2016, asking it to acquire over 2,000 acres of land in ten villages of the district. In March 2017, the government said it would acquire 917 acres in six villages: Motia, Gangta, Patwa, Mali, Sondiha and Gaighat. The administration has so far acquired 519 acres of private land in the first four villages. Acquisition notices in the remaining two villages lapsed in August 2018, with the plant’s land requirements changing.

The company secured environmental clearance for the plant in August 2017, citing Godda’s Chir river as the water source. It now says it intends to draw water from the Ganga in adjoining Sahibganj district, and wants sub-surface rights over 460 acres for a 92-km pipeline to transport water. It also wants 75 acres for a railway line to transport coal.

Had the government turned down the Adani Group’s request, the company would have had to approach farmers to purchase their land, and villagers like Murmu, Hembrom and others would have had a say. On March 24 2017, in a 11-page note, which the Jharkhand government has not made public, the Godda DC declared the proposed power plant to be “for public purpose”, which meant it would acquire from farmers the land the Adani Group sought.

The LARR Act defines “public purpose” as covering several infrastructure activities, including power generation and transmission. But villagers point out that the Adani Group will sell all the power generated at the plant to Bangladesh.

“Adani benefits. Bangladesh benefits. How do we benefit?” asked an agitated Chintamani Shah, echoing the views of several farmers IndiaSpend spoke to.

The state has the first right of refusal for 25% of the power generated by thermal power plants built in the state, which means plants are legally obligated to sell 25% of the power to the state, at rates determined by government policy, according to the Jharkhand government’s 2012 Energy Policy. However, since the Adani Group wants to sell all the power generated at the Godda plant to Bangladesh, a February 2016 MoU between the state government and the Adani Group states that the government has agreed to the company’s request to sell power equivalent to 25% “from alternative sources”.

The government has not made its MoUs with the Adani Group public; the February 2016 document accessed by IndiaSpend is silent on the details of this “alternatively sourced” power. “The MoU is between the company and the state government, I cannot comment on that,” said Pasi when asked for specifics. Officials speaking to IndiaSpend, requesting anonymity, said the company has not provided “clear answers” about where this power will be sourced from and when will it be sold to the state. An Adani spokesperson did not respond to IndiaSpend’s questions on this issue.

The “alternative source” reasoning riles Babulal Marandi, an Adivasi leader and former chief minister of Jharkhand. “How can the state government justify grabbing land from farmers, and giving it to Adani on the grounds that Adani will sell us 25% power from other sources?” asked Marandi. “We can buy power ourselves. The state is already doing it. Why do we need Adani for it?”

An investigation by Aruna Chandrasekhar for Scroll.in in June 2018 revealed how the state government tweaked its energy policy in October 2016, months after signing the MoU, to buy costlier power from Adani. This “preferential treatment”, words used by the government’s own auditors, will result in a Rs 7,410-crore ($1.05 billion) benefit to the Adani Group, Scroll.in reported.

While acquisition of fertile agricultural land to generate electricity for Bangladesh is being called “public purpose”, villagers losing their land for the plant have little or no power. After sundown, electricity lights up Adani’s plant construction site, while the villages around it are swathed in darkness. In Mali and Gangta, on a recent night, people got by with the light of little lamps burning on kerosene, “bought at Rs 50 per litre”, as one villager said.

The 1600 megawatts of electricity generated from the Adani power plant will be sold to Bangladesh. Villages losing their farms and commons to the plant get by on kerosene lamps. The only electricity in the area was at the plant site (right).

“Earlier we used to get power for one or two hours. But since four months, after this company began building its plant here, we have not been getting any electricity,” said a schoolteacher in one of the villages, fanning himself with a textbook as he watched over his wards. “The government is issuing circulars for smart classrooms, and asking us to teach using projectors. And here, children haven’t seen electricity since four months,” said the teacher, requesting anonymity.

A 2016 government report lists even Godda’s district headquarter town as undergoing 18-20 hour daily power cuts.

Social impact assessment silent on impacts

The LARR Act requires the government to conduct a social impact assessment (SIA) to weigh an acquisition’s socio-economic costs and impacts against potential benefits.

Under the law, the SIA study is required to be a publicly available document, circulated and disclosed widely, from gram sabhas in the relevant villages, to government offices and relevant websites. It must detail the extent of private, common and government land to be affected by the proposed acquisition as well as the number of affected families, including the number of displaced. It must assess whether land acquisition at an alternate place was considered and found unfeasible. The assessment also requires that the government hold public hearings to incorporate views of the impacted families.

The SIA report in this case contravened several requirements, we found. It is not publicly available, nor is it placed on any relevant government websites, such as the Godda district website, or the Jharkhand Land Department website. Few villagers like Shah have a copy obtained from “sources”.

Although the SIA states that 5,339 villagers were “project-affected”, it documents the views of only three villagers in the Motia hearing and 13 in Baxara. All the views favour the project and mirror each other. The SIA’s account of the hearings do not record the views of any Adivasi or Dalit residents.

Several locals in the four villages where the government was acquiring land for the Adani Group said that on December 6, 2016, the day of the SIA public hearings, they were barred from attending the proceedings. “There was large police deployment around the hearing site,” said Devendra Paswan, a Dalit farmer .

Only those who had a yellow card or a green card issued by company agents--dalaals as the villagers called them--were allowed in by the police, numerous villagers in Mali, Motia, Patwa and Gangta said. Villagers alleged that the police prevented them from entering even though they were carrying voter IDs and Aadhar cards.

When villagers protested, the police baton-charged and teargassed them, they alleged. Mali resident Rakesh Hembrom said they had no option but to gather outside and protest. “The next day the local paper carried a photo of us with our hands raised in protest, but saying the villagers are in support of the project,” recalled Hembrom.

Residents say they were kept out of the SIA public hearings

In December 2016, several villagers, including women, told a Newslaundry reporter, Amit Bhardwaj, how they were beaten and barred from the SIA hearing site. A local journalist who captured footage of the police violence against villagers in Motia told Bhardwaj the police forced him to delete it.

While the Jharkhand government has empanelled several Jharkhand-based institutions, and public universities, including the area’s Sido Kanhu Murmu University, to conduct SIAs, the SIA for the Adani plant was awarded to a Mumbai-based consultancy firm called AFC India Limited. In the SIA, neither does AFC list the socio-economic costs of the project nor its impact on locals, as it is supposed to.

For example, the SIA omits rudimentary information, such as farming incomes in the area, landholding patterns, the extent of irrigated and multi-crop land, the economic losses for land losers, the impact on women and children, sharecroppers and farm labourers, the extent of common property resources such as grazing grounds and water bodies and the impacts of their loss. The SIA mentions that 97% of the residents are dependent on agriculture, but it does not say how they will get by after losing their land to the plant.

The SIA lists the number of “affected families” in nine villages at 841. But that only includes landholders. Moreover, in the four villages witnessing land acquisition so far, government data has listed 1,328 landholders.

The SIA also claims that the power plant will cause “zero displacement” and that habitations are “very far” from the site of land acquisition. It provides no evidence to support this statement, repeating claims made by the Adani Group in filings to the government, as well as claims by district officials that land acquisition for the project will not displace anyone. The Godda DC’s March 2017 note lists “zero displacement” as one of the grounds for Adani’s plant being a “public purpose” project.

The realities contradict this assertion. For example, the Santali families of Mali, who protested the acquisition bid of August 31, 2018, stand to lose their entire farmland. Their homes abut these farms.

“They may not touch our homes today,” pointed out Sita Murmu, “But without any land, what will we do here and how long can we survive here? We will eventually be forced out.”

In the adjoining village of Motia, at the site of the power plant, the land was being levelled and construction had begun. Construction workers were marking boundary pillars just shy of the walls of the homes of Dalit and Adivasi villagers, such Punam Sugo Devi and Karu Laiyya.

“The company has hemmed us in on all sides,” said Devi. “Where are the poor supposed to go?”

Officials and Adani personnel claim land acquired for a power plant will not displace anyone. But the plant site is enveloping homes of Dalit and Adivasi villagers, such as Punam Sugo Devi and Karu Laiyya (right). “Where are the poor supposed to go?” Devi asks.

“Adani’s people keep telling us every day that we will be evicted from here, this is now sarkar ka zameen (the government’s land),” said Devi’s neighbour Deepak Kumar Yadav. “There is no knowing where they will throw us.” Construction personnel at the site confirmed that they were not taking this area “now”, but, as one said, “it will happen soon.”

Yadav, a landless sharecropper said they were financially hit by the land acquisition, which had subsumed the farms they used to work on – impacts the SIA report was meant to document, but ignored.

“Usually at this time, we would be busy in the fields. But we are without work since the past three months,” said Yadav, adding that they could not even get loans. “Earlier, the moneylender would lend to us against the crop that we would harvest as a sharecropper. Now nobody does so, since they know the land we worked on is gone.”

Sharecroppers and landless labourers say they have lost work and incomes, post-land acquisition

Asked for details of the social impact management and rehabilitation plans—the LARR Act requires these to be in the public domain—Godda’s DC Pasi refused. “That is confidential,” she said. “It contains third party information.”

Land rights expert Usha Ramanathan was a member of the High-Level Committee (2013-14), set up by then Prime Minister Manmohan Singh to report on the socio-economic, health and educational status of India’s Scheduled Tribes. The manner in which the Jharkhand government was taking land and livelihood from farmers demonstrated how “the idea of who, or what, is the public in ‘public purpose’ has got distorted beyond recognition," she said.

Questions of consent

Under the LARR Act, even if the government declares a private project as “public purpose”, it has to secure the “informed consent” of at least 80% of the landholders.

On March 7 and 8, 2017, district officials scheduled nine back-to-back ‘consent’ meetings in the nine villages where 1200 acres of land was to be acquired. The notification did not frame the meetings as a space for villagers to evaluate the acquisition proposal, and award or deny their consent. Instead, the government urged them to consent to the acquisition. According to the administration, in these meetings, and during the 15-day “grace period” following it, 84% of landowners agreed to give their land to the government. The consent process was finished within a fortnight.

The next day, on 23 March, 2017, the Godda government pleader provided a legal opinion to the district administration: since over 80% of the landowners had given consent, the Santal Parganas Tenancy Act--a law that protects Adivasis--“has lost force”, and “land can be acquired even if the area is falling under the SPT Act”. On 24 March, 2017, the Godda administration issued the 11-page note recommending that the government acquire 917 acres of land for the Adani Group. On March 24 and 25, 2017, it issued LARR notifications for the acquisition.

The 1949 Santal Parganas Tenancy (SPT) Act was intended to prevent Adivasi dispossession by placing several restrictions on the transfer of land from farmers in the erstwhile Santal Parganas district, now divided into six districts, including Godda. “There is no provision in the SPT Act for the government to transfer land to a company,” said Rashmi Katyayan, a Ranchi-based lawyer, specialising in land matters. To say that the Act had lost force, Katyayan argued, “was akin to legal fiction that benefits Adani.”

The SPT Act gives powers over the village’s common property (gair mazruwa) lands, such as grazing grounds to village heads, not the government, said Katyayan. But such common lands too have been acquired by the administration and are being given to the Adani group on 30-year leases, while titles of farmers’ land are being transferred to the company.

As with the MoU, the SIA report and the “public purpose” reasoning, the government has not made public the recordings and minutes of the consent meeting proceedings or official documents related to consent. It is hard to verify the government’s claim of consent from 84% of locals independently, since it has not implemented a key requirement of the consent process.

According to rules for the LARR Act, reiterated in the Jharkhand government’s own LARR rules issued in 2015, the landowner’s declaration giving or denying consent must be counter-signed by a district official. The rules state that a copy of this declaration, with the attached terms and conditions, must be handed to the affected landowner. None of the farmers IndiaSpend interviewed possessed these declarations.

Instead, several landholders, especially Adivasis and Dalits, said they had repeatedly refused consent for their land being taken. In Gangta, residents displayed copies of a gram sabha (village assembly) resolution sent to the district administration, the state’s energy department and the governor’s office.

“The gram sabha has collectively decided that it will not give any private or common property land of the village to Adani Power Plant...” said the resolution passed at the meeting held on August 31, 2016. “If we need to give up our lives in the process, we are ready for it.” The resolution is stamped as received by the district administration on September 2, 2016.

An August 2016 gram sabha resolution in Gangta opposed giving land to the Adani Group for the power plant. A September 2018 notice (right) by the Godda administration directed villagers to give consent for handing over gair mazruwa (common property) lands to the Adani Group.

Several villagers alleged that the consent meetings called by the government were flawed and manipulated. “We boycotted them in protest, and have never given our consent,” said Chintamani Shah, adding that he filed right-to-information requests for the consent proceedings and was told that all records have been put on the website. “There was nothing there,” said Shah. IndiaSpend confirmed that was indeed the case.

The official opacity surrounding the project violates several LARR provisions, as well as Jharkhand’s 2015 LARR rules. These rules state: “As early as possible, the government will create a dedicated, user-friendly website that will be a public platform where the entire workflow of each acquisition case will be hosted, tracking each step of decision-making, implementation and audit.” This has not happened.

Officials said that most of the landowners have taken the compensation, which demonstrates consent. Several villagers offered a different perspective. A Dalit landholder in Motia, requesting anonymity for fear of retribution, said that all through, the government presented land acquisition for the Adani plant as a fait accompli, rather than a scenario of free and informed consent.

“My land is surrounded on four sides by that of upper castes,” he said. “Adani’s people told me that I should give the land, else I will be stranded and not get anything. I gave my land and took the compensation of 13 lakh rupees in a state of helplessness.”

Sikander Shah who lost his farm earlier this year, and has taken compensation of around 35 lakh rupees, had a similar account: “Adani’s people told me that if I don’t give consent, I will lose my land, and not get any money. I held out until the very end and finally had to relent.” Shah said that company personnel took him to their office, where he signed some documents. “Laachaar hokay karna pada (I had no choice but to do it),” he said.

Another Dalit famer in Motia, Ramjeevan Paswan, alleged that Adani personnel forcibly acquired his land in February, 2018. “Adani’s officials pushed me, uttering a casteist slur,” he said. “They said if you don’t give your land, we will bury you alive in it.” He filed a case under the The Scheduled Castes And The Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act against Adani personnel Dinesh Mishra, Abhimanyu Singh and Satyanarayan Routray. Nine months on, Paswan said, the police are still recording his statement.

Compensating land for land

Perhaps the most serious impact of the Jharkhand government’s use of the LARR Act to acquire land for the Adani Group, results from its interpretation of the land-for-land compensation principle, laid down in the act for Adivasi and Dalit landowners.

Clause Two in the Act’s Second Schedule states: “..in every project (emphasis added), those persons losing land and belonging to the Scheduled Castes or Scheduled Tribes will be provided land equivalent to land acquired, or 2.5 acres, whichever is lower.” This compensation, the schedule says, is in addition to money.

On June 14, 2017, the Godda district administration wrote to the state government for guidance on implementing multiple compensation and rehabilitation provisions of the act, specifically mentioning the Second Schedule, as well as the Act’s Section 41, which deals with safeguards for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes.

Officials were thus deliberating important aspects of compensation three months after they had called meetings in the villages on March 7 and 8, 2017, and claimed to have secured “informed consent” from over 80% of the villagers.

On September 1, 2017, K Sriniwas, the state government’s director (land reforms), told Godda’s officials that the land-for-land compensation clause for Scheduled Tribes and Scheduled Castes “only applied to irrigation projects.” For this, Sriniwas drew on the preceding part of the land-for-land section, which mentions that land-for-land compensation would be provided in all irrigation projects as far as possible.

Sriniwas is no longer the land reforms director. His successor, A Muthu Kumar told IndiaSpend: “I cannot comment on this. It is a policy decision of the government.”

The land-for-land compensation principle is a critical one, especially for Scheduled Tribes. “Adivasis are intertwined with land, forests and nature,” National Commission for Scheduled Tribes Chairperson Nandkumar Sai told IndiaSpend during a land rights seminar in September 2018. “Land is the very basis of their life, their culture and their identity,” Sai said, echoing the views of the Santalis in Godda’s villages.

In a 29 October 2018 note, following a meeting Sai held with officials of the central ministries of land resources, tribal affairs, and environment and forests, the NCST has drawn on the LARR Act’s land-for-land compensation principle to ask the government to award Adivasis, whom it relocates from tiger reserves, a minimum of 2.5 acres of land as compensation.

The Jharkhand government’s decision to deny land-for-land compensation to Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes “violates Article 14 of the Constitution, i.e. the principle of equality before law,” Ramanathan said. “Whether it is an irrigation project or a power plant, the fact of dispossession is the same across projects. Then how can you compensate with land in one case, but not in another?”

Jharkhand was formed as a separate state in 2000 due to decades of collective struggles for tribal self-determination, and that its government should dispossess tribal farmers thus is “particularly ironic,” Ramanathan said. IndiaSpend asked Kumar, the land reforms director, if it was the Jharkhand government’s stand to deny land-for-land compensation in all LARR projects, barring irrigation projects. “This is the government circular as of now,” said Kumar. “I cannot comment on any future circulars.”

Back in Godda, asked for information on how many Dalit and Adivasi families are losing their land to the Adani group, officials say they have not done “a caste-wise analysis” of those being dispossessed.

The land records in Jharkhand have not been updated since 1932. Documents around the project, including the SIA report, seem to be an unreliable guide. According to the SIA, of the acquisition’s “841 impacted families” (it is counting only land losers), Dalit and Adivasi families number 130, or around 15%. But a basic ground check raises questions about this data.

For example, the SIA lists the number of impacted Adivasi families in Mali village as one. But just one patch of land, which was the target of the controversial acquisition of 31 August 2018, includes 6 families as landowners. Nearly 40 people, across three generations, are dependent on this land. But the SIA states that this land title is reported to be “issue-less”, which means it has no claimants.

Titleholders of this section of land include farmers like Anil Hembrom. Farmers said they would not be able to use the compensation money to buy alternative land, given the SPT Act, which places several restrictions on transfer of farmland in the region. “If the government takes our land from us, we, and our future generations will be condemned to landlessness forever,” said Hembrom. “Our Adivasi existence will be wiped out.”

Adivasi farmers explain why the acquisition will render them landless for good

“Numerous studies, including our report, have shown that communities whose lives are entwined with their habitat, especially Adivasis, have subsistence capability precisely because they have access to natural resources,” said Ramanathan. “If you fence these off from them, you render them immensely vulnerable.”

In Godda, this vulnerability has become a reality for many.

“We cannot even go into what was ours. The company has built a fence all around it,” said Sumitra Devi, a Dalit farmer in her 50s in Motia. Adani personnel threatened and intimidated her family into giving up their land, before eventually forcibly acquiring it this February, she alleged. Devi said her family has not taken the compensation on the grounds that they did not consent to giving their land.

“Humein paise ka moh nahi hai, humein zameen ka moh hai (We have no attachment to money, we are attached to land),” Devi sobbed.“Please find a way for us to get our land back.”

With the land gone, she said, they were struggling to make ends meet, and take care of their 10 cows and calves. She suffered from gastric ailments and diabetes, and did not have enough money for her medical tests and medicines, she said.

On October 8, 2018, shortly after giving this interview, Devi died.

Days after being interviewed about how her land was forcibly acquired, Dalit farmer Sumitra Devi passed away.

(Chitrangada Choudhury is an independent journalist and researcher, working on issues of indigenous and rural communities, land and forest rights, and resource justice. Follow her on Twitter @ChitrangadaC)

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@indiaspend.org. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.