Why Arsenic Found In Pakistan’s Groundwater Should Worry India

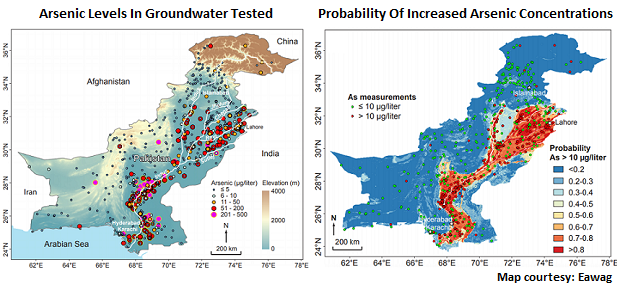

LEFT: The testing of wells in Pakistan revealed which are contaminated with arsenic. This map shows the level of arsenic in groundwater across the valley of the Indus and its tributaries in Pakistani Punjab where some 50 to 60 million people were found to be potentially at risk of arsenic-contamination. Eawag, the Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology led this study.

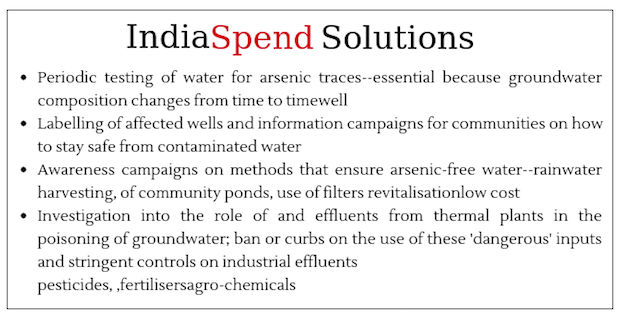

RIGHT: This map shows the probability of increased arsenic concentrations across Pakistan. Many of the hotspots border India, which highlights the need for the testing of wells in Indian Punjab.

Arsenic-contaminated groundwater discovered in Pakistan’s Punjab province during a recent study could affect those living in the bordering areas in India too.

The testing of wells in the valley of the Indus and its tributaries in Pakistani Punjab has revealed that some 50 to 60 million people living in that area are potentially at risk of arsenic-contamination, according to this August 2017 study published in the global journal Science Advances.

“Since the area of high risk extends directly to the border, it likely passes into Indian Punjab,” said Joel Podgorski, groundwater assessment platform project coordinator at Eawag, the Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology. He was the lead author of this research.

The study lists these arsenic hotspots in Pakistan in two representative maps--this showing the level of arsenic in groundwater tested and this the probability of increased arsenic concentrations across Pakistan.

Arsenic is one of the 10 chemicals classified as a public health concern by the World Health Organization (WHO). This is because it can slowly poison the body, potentially causing skin lesions, damage to the peripheral nerves, gastrointestinal ailments, diabetes, renal (kidney) toxicity, cardiovascular disease and cancer.

With this new find, the number of people potentially affected by arsenic-contaminated aquifers globally has increased by roughly one-third, from 150 million people to over 200 million.

At least half of the people who were so far known to be at risk of arsenic contamination live in the Ganges-Brahmaputra basins of Bangladesh and India (West Bengal, Bihar, Jharkhand, Uttar Pradesh, Assam, Manipur and Chhattisgarh).

Punjab’s cancer crisis and arsenic

In recent years, India has also become aware of the contamination of aquifers in Punjab with arsenic and heavy metals such as uranium and mercury. The telltale sign is the alarming increase in cancer cases in southwest Punjab’s fertile Malwa region, comprised of the districts Mansa, Faridkot, Moga and others.

In a 2007 zonal groundwater study in Punjab, every single sample drawn from aquifers of the aridic southwestern region had an arsenic concentration higher than the WHO-prescribed 10 micrograms per litre (µg/l) cut off for drinking water.

Arsenic concentrations ranged from 11.4 µg/l to 688 µg/l and averaged 76.8 µg/l, which is 53% higher than the upper permissible limit (50 µg/l) for drinking water established by India’s Central Groundwater Board.

Two other zones comprised of the other parts of Punjab had lower arsenic concentrations, averaging 23.4µg/l and 24.1µg/l, respectively, but fared hardly better in water quality for drinking purposes. Barely 3% and 1% of the samples from those zones met the WHO-prescribed safe norm.

But the Central Groundwater Board’s state groundwater profile for Punjab lists only Amritsar, Taran Taran, Kapurthala, Ropar and Mansa as areas of concern for arsenic contamination. So Podgorski’s study is significant because it highlights the pressing need for closer monitoring of groundwater in other parts of the state as well and the need for safe drinking water campaigns.

Testing water samples from wells is the only way to know which are affected, whether in Pakistan or India, said Podgorski.

Prevention is vital--chronic poisoning has no cure

Controlling the source of arsenic contamination, where it happens due to anthropogenic (human activity) causes, is more important than trying to remedy arsenic contamination in humans or in the environment, said Saroj Arora, a professor of botanical & environmental sciences, Guru Nanak Dev University, Amritsar, who has studied arsenic contamination in Punjab.

Chronic arsenicosis or arsenic poisoning has no cure per se although switching to clean water can improve arsenic-induced skin lesions, said Debendranath Guha Mazumder, a member of the core committee of the task force on arsenic for the government of West Bengal.

Take the example of Tofijul Ali, 39, a small contractor and tea grower and member of the panchayat of Kachari, a village in Jorhat district, Assam. Ali had been suffering from frequent bouts of gastric pain--an early symptom of arsenic contamination. He wasn’t the only one in his family or village. His own daughter and many other children studying at the Melamati Government School too reported sick with similar symptoms. When Anant Khanikar, the school’s headmaster, with the help of a local engineer and member of Arsenic Knowledge and Action Network investigated the matter, he learned that the tubewell water his pupils and many villagers were drinking was contaminated with arsenic.

Tofijul Ali, 39, a small contractor and tea grower and member of the panchayat of Kachari, a village in Jorhat district, Assam, suffered from frequent bouts of gastric pain--an early symptom of arsenic contamination. His daughter also had the same problem. He approached a doctor for their problem, they took medicine but the pain persisted until they switched to harvesting and drinking rainwater. Arsenic poisoning has no cure making prevention imperative.

Ali switched to drinking harvested rainwater in 2012 and he and his daughter recovered soon after.

“A doctor had treated us for the pain but it did not work,” Ali told IndiaSpend. “But three to four months after we switched to harvested rainwater we recovered.”

Jorhat is one of many districts across India where the people simply do not know that they are being slowly poisoned by arsenic.

A high protein diet and selenium, vitamin (A, B complex, C, E) and antioxidant supplementation can speed up recovery from arsenic-induced skin lesions, according to Arora.

Arsenic seeps into the food chain

Bacteria-laden surface water is what prompted the installation of tubewells for drinking water purposes back in the 1970s in Bangladesh. A similar move in West Bengal eventually led to India’s first-known case of arsenic poisoning, a patient who had developed skin lesions, in 1983 in Kolkata.

But even if you purify drinking water, arsenic in groundwater used to irrigate crops could make its way into the food chain, pointed out Arora.

In Punjab, agricultural inputs such as pesticides, fertilisers and agro-chemicals and effluents from thermal plants have also been blamed for the arsenic in the groundwater. Awareness campaigns to educate farmers about safe agro-chemicals and stringent control on industrial effluents are badly needed, Arora said.

Drilling deeper wells is not the solution

In the Ganges-Brahmaputra basins, studies—such as this (Environment Asia, July 2017) and this (Frontiers of Environmental Science, 2014)—have found high concentrations of arsenic in water samples drawn from shallow aquifers, roughly 12 m to 35 m below ground. “[Usually], the values from deeper points are less,” the Frontiers of Environmental Science study said.

Essentially, deeper wells in those basins may yield cleaner, safer water but drilling deeper is not advisable from the environmental perspective.

“Groundwater systems are best not tampered with because unlike water in shallow aquifers, the water does not get replenished directly from rainfall due to the formation of different sedimentary layers,” said Guru Balamurugan, chairperson of the Centre for Geoinformatics, Jamsetji Tata School of Disaster Studies, Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai. He is also the co-author of the aforementioned Frontiers of Environmental Sciences study.

Drilling deeper wells is not even a temporary solution in Pakistan. “The arsenic problem in Pakistan occurs in a differing geochemical environment so, for example, drilling to access arsenic-free water may not necessarily work. But this would need to be investigated further,” said Podgorski.

Purifying arsenic-laden water: Easier in Punjab than Bengal basin

In Assam and Bihar, a few communities use traditional filters made of layers of charcoal, brick and sand to purify water.

“We found this interesting because the charcoal in the filter would absorb some arsenic,” said Balamurugan of his study experience in West Champaran, Bihar. “So the efficacy of the filter to remove arsenic would depend on the charcoal being periodically changed.”

Safeguarding entire communities would necessitate technology to filter a large quantity of water.

Several technologies exist, which can be applied in community plants attached to hand pump tubewells or large diameter tubewells, to remove arsenic from groundwater, said Guha Mazumder. “Domestic filters based on these technologies can also be developed.”

A positive for Punjab is that “the arsenic species likely present throughout much of the Indus Plain (As+5) is significantly easier to filter out than the more reduced species (As+3), which is predominant in the Bengal Basin,” said Podgorski. So, he reckons low-cost filters such as the Sono household filter used in Bangladesh, costing supposedly only about $35, could help people there.

Indian scientists have also developed a low cost arsenic filter that has so far been successfully tested in West Bengal. Clearly, millions more are in need.

Note: The maps in the lead image were prepared by US researchers and do not depict India's boundaries as India denotes them.

(Bahri is a freelance writer and editor based in Mount Abu, Rajasthan.)

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@indiaspend.org. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.

__________________________________________________________________

“Liked this story? Indiaspend.org is a non-profit, and we depend on readers like you to drive our public-interest journalism efforts. Donate Rs 500; Rs 1,000, Rs 2,000.”