Why Audits, Reconciled Death Data Are Still Missing COVID Deaths

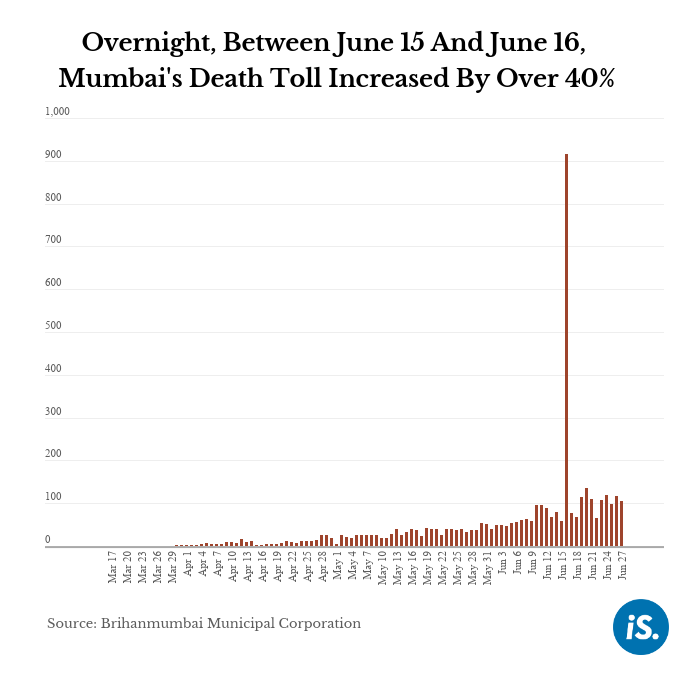

Chennai: On the night of June 15, the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) issued its usual COVID-19 evening bulletin and tweet for Mumbai, then the Indian city with the most COVID-19 cases. The city’s COVID-19 death toll was 2,248, including the 58 new deaths, it announced. By the next morning, the numbers had jumped by about 40%--on June 16, the BMC’s evening bulletin announced 3,165 deaths, including 862 older but previously unreported deaths.

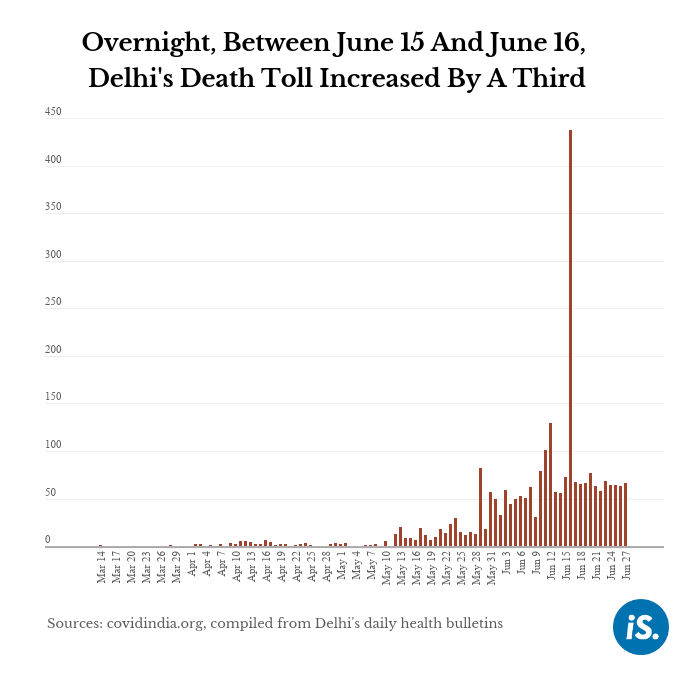

Halfway across the country, a similar story played out in Delhi, currently India’s worst-hit city. On June 15, Delhi’s state health bulletin reported 1,400 deaths including 73 that day. On June 16, there were 93 new COVID-19 deaths but the cumulative total had grown by one-third to 1,837, the bulletin showed.

These increases came about as a result of “death data reconciliation” exercises that at least three states--Maharashtra, Delhi and Tamil Nadu--have undertaken, in order to fix lags, misreporting and other errors in the reporting of COVID-19 deaths by hospitals and municipal corporations. A detailed examination of the COVID-19 deaths data that reach state governments--and in turn, the central government and the public--reveals both areas of concern and hope, as per former health administrators and experts.

Death audit committees’ fuzzy workings

The protocol on recording deaths during the current pandemic comes from the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR). It clearly lays down (see box) under what circumstances a death ought to be certified as a COVID-19 death.

The ICMR’s “Guidance for appropriate recording of COVID-19 related deaths in India” was authored by Prashant Mathur, director of the ICMR’s National Centre for Disease Informatics and Research. Written in jargon-free and simple language complete with examples of various scenarios that doctors and hospitals might face, the document makes four important points about recording COVID-19 deaths:

- Even if a COVID-positive person dies without symptoms of the disease, the death should be recorded as a COVID-19 death under U07.1, the World Health Organization’s (WHO) International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) code for a confirmed COVID-19 death.

- Even if a positive patient appears to die of respiratory failure, the underlying cause of death--as distinct from the mode of death--should be listed as COVID-19.

- If a COVID-positive person has comorbidities, the patient has a higher risk of dying of respiratory failure. But the comorbidities should not be listed as the underlying cause of death; the cause of death remains COVID-19.

- If a person dies without being tested for COVID-19, or had tested negative but displayed COVID-19 symptoms, the death should be classified as a “suspected or probable COVID-19” death.

However, on the ground, things play out quite differently. Some states such as Tamil Nadu and Delhi have constituted state-level “Death Audit Committees”, which go through the COVID-19 death certificates to determine how many of these are “real” COVID-19 deaths, before announcing a final number daily. Mumbai has death committees at the BMC level, the Mumbai Metropolitan Region and at the state government level.

From their perspective, the committees are essential to reconcile inconsistencies in the data. “We are dealing with municipal corporations governed by a party opposed to ours which is invested in inflating their numbers,” said an advisor to the Delhi government who liaises with the death audit committee, on the condition of anonymity. “The major hospitals are overworked and also not working with us to report the data quickly. So, the committee is essential to scan the certificates and determine which of them really are COVID-19 deaths.”

As with Delhi, the workings of these committees are political and contested in other states too. Following weeks of back-and-forth with the central government over the mode of reporting deaths and the final numbers, West Bengal wound up its Death Audit Committee. In other states, the committees might be less controversial, but they do not readily share data, as we found.

IndiaSpend spoke to members of death audit committees in four states (Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, Delhi and Uttar Pradesh) and not one agreed to share details of how many cases had come before them and how many they had certified as COVID-19 deaths. Tamil Nadu shot into national headlines after a committee constituted by the state’s Directorate of Public Health examined Chennai city corporation records and found that 236 death certificates that mentioned COVID-19 had not been notified to the state government as COVID-19 deaths. Those deaths had not been automatically added to the city’s or the state’s COVID-19 tally. The process of reconciliation was still on and the state government had set up a nine-member committee to audit all COVID-19 deaths, M. Jagadeesan, Chennai’s Chief Health Officer, told IndiaSpend on June 23.

A similar situation played out in Mumbai: 347 COVID-positive persons undergoing treatment had died, but the BMC labelled them as non-COVID deaths in violation of ICMR protocol. “This happened with the Mumbai district Death Audit Committee. We have asked for all deaths of COVID-19 positive persons except for accidental deaths to be counted as COVID-19 deaths. That reconciliation process is ongoing,” said Avinash Supe, the former dean of Mumbai’s King Edward Memorial (KEM) Hospital who heads a Maharashtra government-appointed committee to audit Mumbai’s deaths.

Ezhilan Naganathan is a consultant physician and diabetologist with Kauvery Hospital in Chennai. He has been attending to COVID-19 patients every day for more than two months. “There is no transparency in the state government’s decisions about which deaths are being declared as COVID-19 deaths. From what we are seeing in the city, we have reason to believe that numbers are being suppressed,” he said.

Prabhat Jha, a professor of global health and epidemiology at the University of Toronto, is a lead investigator of the Million Death Study in India, a project that estimated the ‘true’ causes of mortality in a million households where a death had occurred, using “verbal autopsies”. “During an epidemic, you want to err on the side of overestimating deaths, not underestimating them,” said Jha, adding that there were increasing findings that COVID-19 did not just cause respiratory but also vascular and other deaths. “That’s an argument for sticking to the most liberal definition of a COVID death. If it says anywhere COVID-19 or suspected COVID-19, it should be declared as a COVID death. [This] in turn should mean that the guidelines for each of the state adjudicators or auditors should be unambiguous,” said Jha, who is also the founder and executive director of the Centre for Global Health Research at Unity Health Toronto.

The missing dead

Then there are all those deaths that never make it to the committee.

“At the moment, deaths that take place at home and get a certificate from the local GP [general physician] don’t make it to our committee,” said the advisor to the Delhi government. “Most of these private practitioners, anyway, would not write ‘Suspected COVID-19’ on the death certificate because of the stigma, quarantine and the whole process associated with it.” However, at cremation and burial grounds, some of these suspected cases would be given ‘COVID-19 funerals’ to minimise exposure, sometimes even in deaths not caused by COVID-19, he said. This explains why the suspected COVID-19 death data from burial and cremation grounds was higher than the official toll, he added.

Officials in Mumbai, Delhi and Chennai told IndiaSpend that they had not yet certified any deaths under U07.2, the ICD-10 code for suspected or probable COVID-19 deaths, despite the ICMR guidelines. “All COVID-19 deaths in Delhi are in big institutions only,” a member of the state’s Death Audit Committee insisted. “We have received some forms with U07.2 but we have not yet certified any suspected COVID-19 deaths,” said Chennai’s Jagadeesan. Meanwhile in Mumbai, “all the death certificates right now are with confirmed COVID-19 test and issued by hospitals,” said Rajesh Dere, head of forensics at Mumbai’s Lokmanya Tilak Municipal General Hospital. “We have only been tasked with looking at death reports of those who tested positive for COVID-19,” said Supe, who heads Maharashtra’s Death Audit Committee for Mumbai. The committee had not been asked to even look at suspected or probable COVID-19 cases.

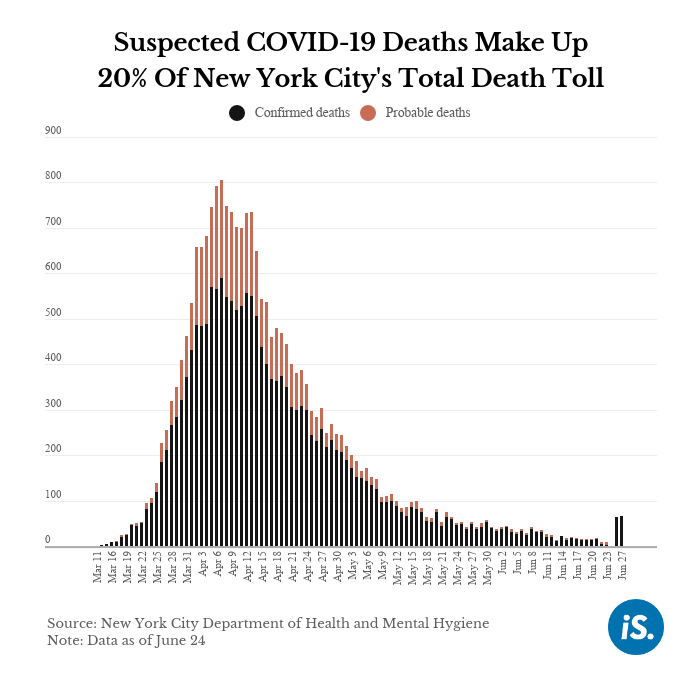

This means that India might be missing many deaths among people who did not or could not get a COVID test. In New York City, for instance, one-fifth of the total deaths are attributed to suspected COVID-19 cases.

Across the world, COVID-19 deaths are being underreported for different reasons, and such audit panels are reconciling the data to provide better estimates, said Jha. “Provided the audit committees are following the WHO procedures and reporting them as per WHO guidelines, COVID-19 deaths need not have a confirmed diagnosis. It is actually a mistake as we have learnt in the Netherlands (which first only reported RT-PCR confirmed deaths and then realised they were missing 20-30% of deaths), France, the UK and belatedly in Canada’s Quebec province,” Jha said. The missed deaths originate in nursing and elder care centres in some countries, and from home deaths in others, Jha said, and the reconciled numbers came as a result of adding these in, and from excess mortality estimates.

“I suspect what’s going on in India is a combination of things: One, the systems followed by the state and hospitals to compile data are different. The second concern is if they are reporting only PCR-confirmed deaths, then they are certainly missing some deaths because not all COVID-19 deaths get tested,” he added.

Towards an Independent audit

In addition to COVID-positive persons clearly dying of respiratory failure in large hospitals, the government should be proactively seeking out those who die at home or outside hospitals, said Naganathan, the consultant physician and diabetologist from Chennai. “In a pandemic, any sudden death of an elderly person or patient with known comorbidities should be investigated, but this is not happening. They are conducting autopsies in medico-legal cases only,” he said, adding, “When patients come to casualty or emergency [wards] in government hospitals, samples are not being taken even if they demonstrate COVID-19 symptoms... only a tentative diagnosis is being given. The government should take another look at all these death certificates.”

The ICMR should come out with clear protocols about testing dead bodies, Dere said. “For example, if they say all bodies should be tested for COVID-19, then we will know clearly what to do,” he said.

“Given India’s low testing rates, non-tested deaths are definitely an area of concern. Remember, we are talking about a situation when only 15-20% of deaths at the best of times are medically certified,” said Keshav Desiraju, India’s former health secretary. What is being reported is from the big cities; in rural areas, death certification is even rarer and the administrative structure for reporting deaths is “messy”, added Desiraju.

So, how can states best audit the data they are receiving to make sure deaths are being accurately reported? The Death Audit Committee is a good arrangement, said Desiraju. Pandemic or not, the death certificate rests on the judgment of the doctor issuing it and that needs oversight, he said. The problem is the current environment. “We suspect now that these committees might conceal some deaths because it has become very political. The occurrence of deaths is seen as a lack of governance. I am sure there is some sort of informal directive that if you can possibly disguise these deaths... do so,” he said.

While the committee is essential, and the fact that it is operating under pressures is also known, the next step should be to empower these committees, said T. Sundararaman, former director of the National Health Systems Resource Centre, a government body that worked as a think-tank for the National Health Mission. Sundararaman is now global coordinator of the People’s Health Movement advocacy group and adjunct faculty in the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences at the Indian Institute of Technology-Madras.

“The committee should have external members from academia or civil society. Since it is performing an audit, it requires some separation from the health establishment. There should be independent committee members who would be willing to exercise their powers, call data and documents on record, see tallies, ask for samples and compare these with recorded deaths,” he suggested. “In the short run, state governments might think they are saving themselves by suppressing the data. But in the long run, they would be the ones who would have to pay, especially when the disease spreads to the districts,” he warned.

Interview with Prashant Mathur, Director of the National Centre for Disease Informatics and Research of the ICMR

Most states have set up a Death Audit Committee which audits all the death certificates to determine the number of 'real' COVID-19 deaths. Is this an ICMR-recommended mechanism? Is there concern that this might create perverse incentives, especially since these committees' proceedings are closed to the public?

ICMR has not recommended Death Audit Committees to the states.

The constitution of Death Audit Committees is a public health strategy undertaken by the health departments in states to review the circumstances of the death, the cause of death, identify the possible reasons that led to the death and the factors that could have prevented the death. Such committees have both external members and health department officials and are usually constituted for specific health conditions. These committees primarily help in devising strategies for case detection, clinical management, health system response and their implementation. The committee also reviews the causes of death due to COVID-19 and ensures that the comorbid conditions are recorded accurately.

As COVID-19 is a new disease with new ICD-10 codes and risk of mortality is directly proportional with increasing age and comorbidities, ICMR published the Guidance document for appropriately recording the cause of death in COVID-19 related deaths.

Most states have not yet certified any U07.2 deaths (suspected or probable COVID-19 deaths). Given that suspected COVID-19 makes up a significant portion of global deaths, could the states be asked to report such deaths separately?

The World Health Organization (WHO) has provided U07.2 for probable or suspected COVID-19 in the absence of testing. The WHO has also recommended that U07.1 codes may be used for reporting COVID-19 deaths in countries that may not report laboratory confirmation of COVID-19 on the death certificate. So U07.1 may indicate both laboratory confirmed and probable or suspected COVID-19 deaths.

In due course, as the clinical definitions of COVID-19 are well established, the codes of U07.2 may be adopted by the respective health departments.

What is the best way to ensure that deaths taking place at homes and outside of hospitals without a microbiological test are included in the overall statistics?

Deaths that take place at home or outside the hospital and [where] there is lack of laboratory test confirmation have to be reported to the Civil Registration System for death registration. Standard protocols may be provided by the health departments to the local registrars to record suspected or probable COVID-19 deaths. The questions should include presence of any COVID-19 symptoms, exposure to COVID-19 positive patients, sequence of events of death that include respiratory failure, and associated comorbidity.

Such deaths could be registered in two ways:

- Medical certification of cause of death (Form 4A) by the attending physician or family doctor who is aware of the sequence of events and the causes that led to the death should be submitted with the death report (Form 2) to the Local Registrar of Births and Deaths of the Civil Registration System.

- Even when a medically certified cause of death (Form 4A) is not available, there is a provision to record the probable cause of death as reported by the family or relatives of the deceased in the death report (Form 2) during the death registration process.

Presently, the data on cause of death using the two ways mentioned above is neither complete nor accurate and hence it is not reliable to be reported as statistics. Strengthening of systems to record and report cause of death in the civil registration system could facilitate improving overall statistics.

This is the second part of an ongoing investigation into India’s COVID-19 mortality. You can read the first part here.

(Rukmini S. is an independent journalist based in Chennai.)

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@indiaspend.org. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.