Why Compensation For Wildlife Attacks Works Against Its Aims In India

New Delhi: The small town of Pandharkawada lies 150 km south of Nagpur in eastern Maharashtra. Surrounded by forest and agricultural fields, this off-the-map town is in the news: A young predator tigress with cubs has been on the prowl here for 18 months now, wreaking havoc.

So far, she has killed 14 people; three of these deaths were reported in August 2018 alone. The state government is making an attempt to capture and tranquilise her, failing which she will be shot-on-sight as was decided earlier.

Tigers predating on humans is not the natural norm but when it happens, it has damaging consequences: On the one hand it causes social, psychological and economic loss to the individual and the community and on the other, the loss of gene pool when an endangered animal is put to sleep. More common than attacks on human beings is big cat predation on livestock.

Nagaon: Wild elephants in paddy fields

The most common damage caused by wildlife is the destruction of crops by elephants, deer, antelopes, wild boar and other wildlife. This results in economic and psychological distress among farmers. In retaliation, wild animals are poisoned or left injured through crude devices. Elephant-related conflict alone has damaged 0.8–1 million hectares of crops every year and destroyed 10,000-15,000 properties, as per the 2010 report of the Elephant Task Force, ‘Gajah: Securing the Future for Elephants in India’.

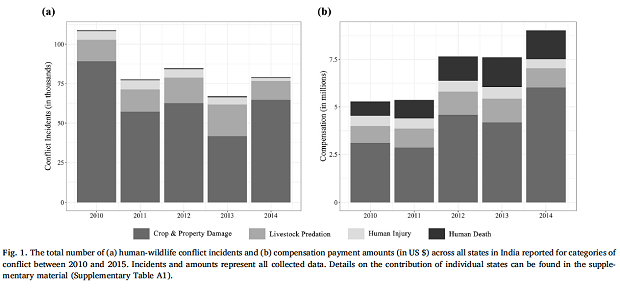

Between 2010 and 2015, the annual figures for man-animal conflict incidents in India ranged between 66,940 and 108,853, as per a new research paper titled ‘Compensation Payments, Procedures and Policies Towards Human-Wildlife Conflict Management: Insights from India’. The first study of its kind, it was published in July 2018 in the journal Biological Conservation. Currently, 88 species of wild animals feature in this conflict.

Contrary to popular perception, wildlife is not limited to national parks and sanctuaries; it knows no human-drawn boundaries and in some habitations, shares resources with humans. For example, 30% of India’s tiger population (800) resides outside tiger reserves; and a large section of the elephant population keeps crossing human habitations on its journey to wildlife sanctuaries.

Monetary compensation for the loss of lives and livelihood is a major tool used by governments to reduce the man-animal animosity. But how effective is the government compensation for the loss suffered due to wildlife conflict?

‘Is India a high-conflict, low-compensation country?’

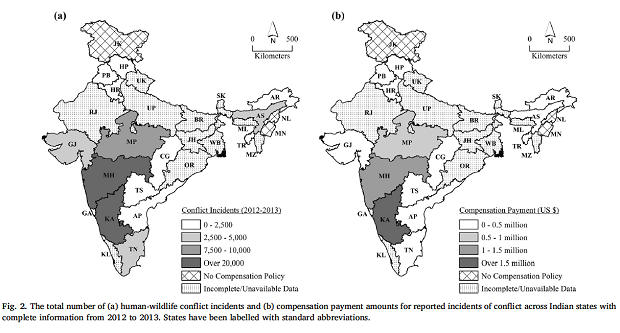

“(Of) India's 29 states, 22 (76%) compensated for crop loss, 18 (62%) for property damage, 26 (90%) for livestock depredation, and 28 (97%) for human injury or death,” said the study by Krithi K Karanth, Shriyam Gupta and Anubhav Vanamamalai of the Centre for Wildlife Studies, Bengaluru.

In 2012-2013, 78,656 conflict incidents were reported from 18 states and compensations totalled Rs 38.6 crore, as per the study. The average expenditure per incident worked out thus: For crop and property damage, Rs 3,406; for livestock, Rs 5,363; for human injuries, Rs 7,465; and human death, Rs 233,715.

Maharashtra paid the most for human injuries, Rs 1.15 crore, followed by Madhya Pradesh, Rs 1.12 crore. The average sum disbursed across all states was Rs 24.15 lakh.

Compensation schemes are vulnerable to corruption and lack transparency, said the study. Further, they are inefficiently disbursed and provide meager support and that too after administrative delays and harassment. This is why instead of reporting their loss to authorities they choose retaliatory killings, the study concluded.

Maharashtra pays 8 times more for human fatality than Assam, AP

Not all states in India have a uniform compensation policy. Twenty-two states paid compensation for crop damage caused by wildlife, and of them, 16 followed a defined crop list. Eighteen states made payments for property damage or loss, but the definition of ‘property’ varied from state to state. Twenty-eight states provided compensation for human injury or death attributed to wildlife.

Disbursements also vary between states as per category of loss suffered. For example, Maharashtra pays eight times more for a human fatality than Assam or Andhra Pradesh. Haryana and Jharkhand have different compensations for minors and adults.

“The numbers do not represent the true picture of the ongoing human-wildlife conflict scenario because of the unavailability of records from all states, incomplete data in some cases and low reporting of incidents,” said Karanth. “There is a lack of policies in some states (Manipur and Nagaland had no policy regarding wildlife-caused injury or death. Rajasthan has no policy for crop damage), while others have low payment amounts along with high transaction costs. Further, there are inconsistencies in eligibility, application, assessment, implementation, and payment procedures across states.”

The lack of consistency in rates across states may be a bigger issue than the lower rates themselves, according to the study. And unless compensation reaches all affected people through a common, transparent and efficient process, managing human-wildlife conflict will remain a significant conservation challenge.

The study suggested prevention of conflict situations as a better option that high compensations. “In India, conflict incidents related to crops, property, and livestock comprised 94% of losses and 72% of payments. These could be reduced by integrating early warning systems with simpler damage-prevention practices (such as improving fencing of crops or better livestock husbandry) in conjunction with simpler and more efficient processing of claims,” it said.

Compensation alone will not lower incidents of retaliation against wildlife, the experts said. “There is a need to monitor and measure these perceived changes in the attitudes and actions of affected people,” it stated.

(Banerjee is a conservation journalist, author and artist.)

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@indiaspend.org. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.