Why Hundreds Die Of Lightning Strikes Despite New Technology, Programmes

New Delhi: With the country fighting a pandemic, the deaths of over 200 people due to lightning strikes over the last four months have largely gone unnoticed--barring the catastrophic day in June when 83 people were fatally struck in Bihar, leading the Prime Minister to tweet his condolences to the bereaved families.

For experts closely tracking these deaths, the spate of fatalities every year due to lightning strikes before and during the monsoon months are mostly preventable. Early warning systems (EWS) to forewarn against thunderstorms and lighting strikes have improved significantly, Madhavan Nair Rajeevan, secretary, Union Ministry of Earth Sciences (MoES), told IndiaSpend.

“Earlier, lightning detectors had a range of 200 to 300 sq km, now it has improved to 40 sq km,” he said. “Last year, we developed a weather prediction model exclusively for predicting thunderstorms, and we are predicting them almost 24 hours ahead, and then using radars to further track them, giving us a three-hour lead.”

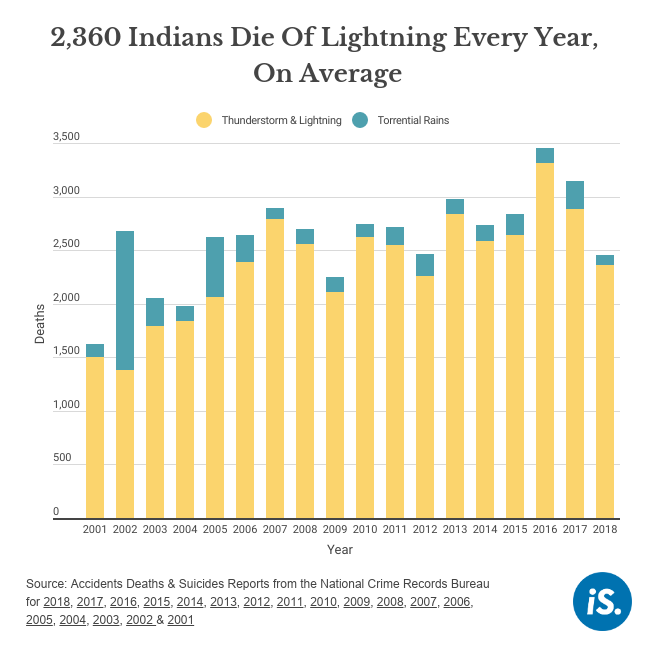

Yet, 2,360 Indians die every year, on average, due to lightning strikes, our analysis of data from the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) since 2001 has shown. Lightning has remained the largest single cause of deaths due to natural disasters every year since 2002. (In 2001, 13,702 people had died of the earthquake in Bhuj, Gujarat.) Over 40,000 lives have been lost to lightning since 2001.

Since 2019, the Lightning India Resilient Campaign, launched by the Climate Resilient Observing Systems Promotion Council (CROPC), MoES and other agencies, in tandem with NGOs, has set itself the task of reducing such deaths by 80% by 2021. The challenge, experts concur, is ensuring last-mile connectivity, that is, making sure states relay the benefits of improved forecasting to vulnerable people and install lightning arresters in rural areas. Odisha is an example of a state that has reduced lightning deaths by installing arresters.

There is a growing global interest in monitoring lightning strikes, which are seen as both a cause and a symptom of climate change.

More than 40,000 deaths in 18 years

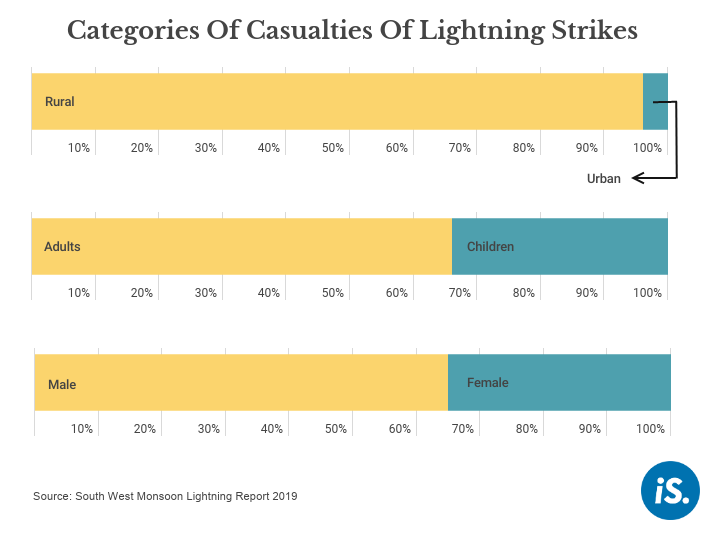

Nearly 42,500 people were killed due to lightning strikes between 2001 and 2018, according to NCRB data (see chart) on accidental deaths. The large proportion of these deaths were in rural India, with only 4% in urban settings, the South West Monsoon Lightning Report 2019, brought out by the Lightning Resilient India Campaign, shows.

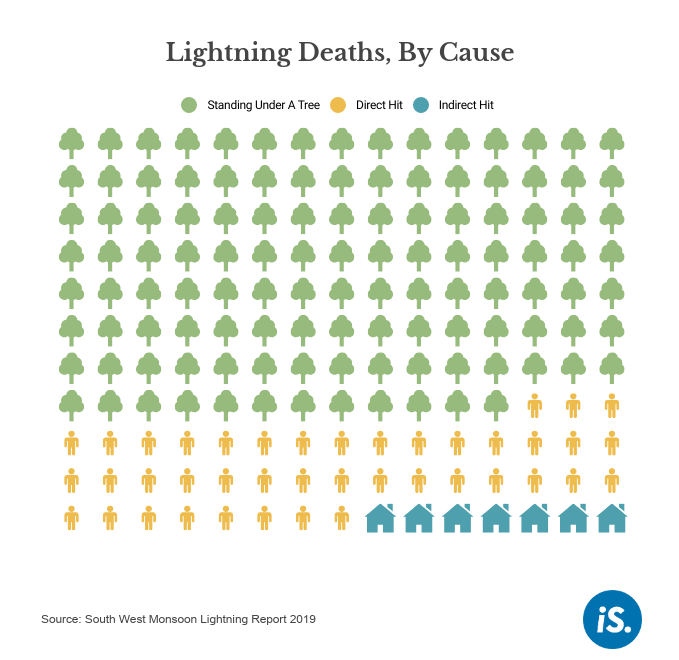

Seven of 10 deaths were of those sheltering under trees in the face of heavy rain, thunder and lightning, the report shows. They were electrocuted when the trees were struck by lightning.

Further, about one-fourth of victims were those hit directly while out and about in the open, among them farmers, labourers, cattle-grazers, people collecting firewood and fisherfolk, the report shows. Those sheltering in pucca structures are best protected against lightning, according to experts. Only 4% of deaths are of those hit indirectly.

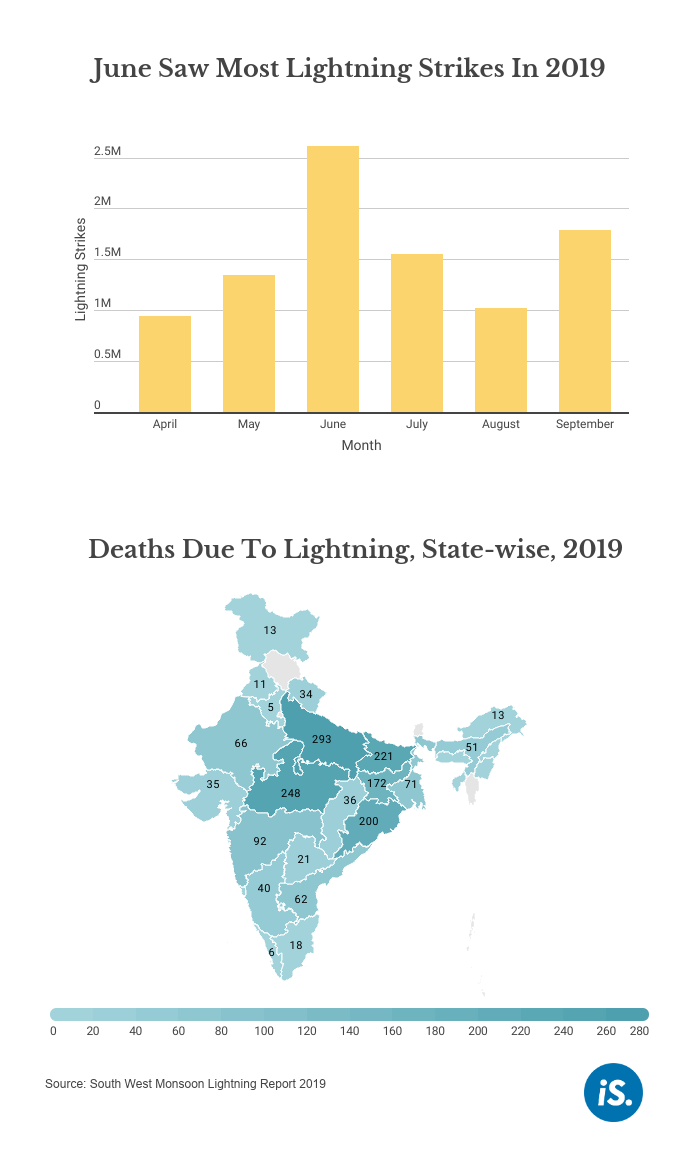

Among Indian states, Uttar Pradesh (UP), Madhya Pradesh, Bihar, Odisha and Jharkhand reported the highest number of lightning fatalities in the country in 2019.

This year on the same day in June that 83 people were killed in Bihar, 30 people died in lightning strikes in UP.

In 2018, lightning deaths accounted for the largest share (34.2%) of more than 7,000 accidental deaths due to forces of nature, according to the NCRB’s report on Accidental Deaths and Suicides in India 2018. In contrast, deaths due to heat-stroke and exposure to cold accounted for 12.9% and 11%, respectively.

Lightning strikes also kill wild animals and livestock, cause substantial damage to property and injuries to people trapped in damaged properties.

Campaign to resist lightning strikes

After a large number of people were killed by lightning in April and May 2018 in northeast India, and subsequently, a further 80 perished near the borders of western Uttar Pradesh, Haryana and Rajasthan, the Union government set up an expert committee of India Meteorological Department (IMD) scientists and top officials from the MoES, to devise models for better forecasting and mitigation of the impact of lightning strikes.

This led, the following year, to the formation of the Lightning Resilient India Campaign, a joint initiative by the CROPC, the IMD, the MoES and the NGO World Vision India.

In its mission to eliminate most lightning deaths, the campaign focuses on analysing multiple data sets and satellite images in order to zero in on vulnerable areas and ensure that all line agencies communicate timely warnings to areas likely to be struck by lightning. It also helps state agencies build their capacities for mitigating the impact of lightning strikes, and tries to build awareness on the ground.

“Thanks to the tie-up with World Vision India, the campaign has access to a volunteer network of about 15 lakh [1.5 million] people spread across India for the much-needed last mile connectivity,” Sanjay Srivastava, chairperson of CROPC, told IndiaSpend.

In November 2019, the campaign brought out The South West Monsoon 2019 Lightning Report, the first ever scientific mapping of lightning strikes in India aimed at improving the preparation of lightning risk maps for every state. It shows the places most likely to be hit by lightning, and thus gives the affected states pointers for where they should build shelters and erect lightning arresters, among other interventions.

“Nowcasting”, mobile app for lightning strikes

Thunderstorms and lightning being fast-evolving meteorological phenomena, precise forecasting is a challenge. Yet, there has been progress over the past two years, with the real-time collection of scores of images and data from across India that is then pieced together by experts.

Inputs include satellite images from the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO), IMD’s doppler radars, the Indian Air Force’s sky observations and data from the sensors/lightning detectors used by the Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology (IITM, Pune).

“IMD follows a seven-step protocol on a daily basis to forecast thunderstorms and issue lightning warnings,” explained Soma Sen Roy, a senior scientist at the National Weather Forecasting Centre (NWFC), IMD. The final step consists of preparing three-hourly ‘nowcasts’, which are specialised weather forecasts zeroing on smaller areas, such as individual districts or IMD stations. The stations warn district collectors about impending strikes.

Roy emphasised that the three-hourly nowcast is widely disseminated through IMD’s network to disaster management networks in all states and union territories and, through its social media platforms, to the general public as well. “Three to four years ago, there was no now-cast system in the IMD,” Rajeevan, the MoES secretary, pointed out. (IMD and IITM are both agencies under the MoES.)

Using data generated by IITM-Pune’s Lightning Location Network, a mobile app, ‘DAMINI: Lightning Alert’, was launched by the MoES in November 2018. Downloaded by about 100,000 people, the app gives the exact location of current lightning strikes, and the probable locations of impending strikes to users in an area of 40 sq km, so they can take shelter. It also lists the dos and don’ts to be followed during thunder and lightning events.

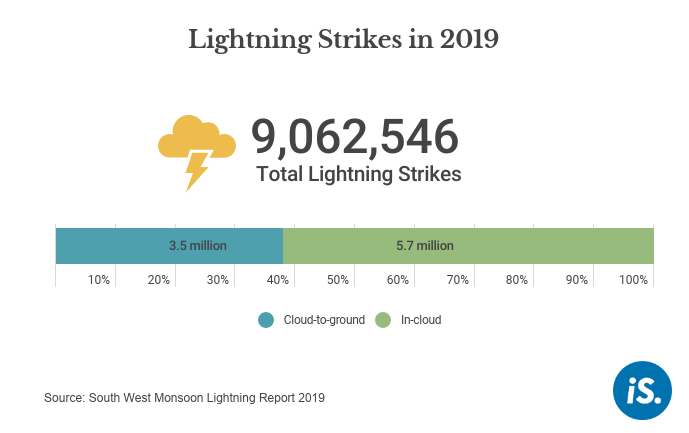

In the atmosphere, there are mainly two types of discharges: in-cloud (intra-cloud and inter-cloud) and cloud-to-ground (CG). Mid-air aircraft can be hit by in-cloud strikes while the CG type takes a toll on life and property on land or sea.

In 2019, there were more than 9.2 million lightning strikes across India, of which 62% (5.7 million) were in-cloud and the rest (3.5 million) were cloud-to-ground.

The data above cover the 25 states with the maximum number of lightning deaths during the southwest monsoon in 2019. The death toll for the whole country in 2019, according to this report, is 1,771. These data are based on reports received from state governments, reports by media and data collated from volunteers from across India. NCRB’s figures for 2019 are not yet available.

Source: South West Monsoon Lightning Report 2019

Note: Data for Jammu and Kashmir are for the erstwhile state, including for the union territory of Ladakh

Most people in rural areas who fall victim to lightning strikes are those sheltering under trees during rainfall, thunderstorms and lightning. A tree in an open field attracts lightning due to its height and thus the chances of people standing under trees being hit are the highest, relative to other situations.

Then, there are farmers, labourers, cattle grazers, men and women collecting firewood and in some cases, even fisherfolk, who happen to be out in the open when lightning strikes them directly. The third category is the indirect hit, when lightning hits a structure, which leads to casualties among those within it/near it.

Poor last-mile connectivity

“But ultimately we cannot go to each individual,” Rajeevan conceded. “The communication reach is not that good, it needs to be improved.”

The Lightning Resilient India Campaign has “helped a lot”, he said, adding, “NDMA [National Disaster Management Authority] has done some campaigns to create awareness [but] we need to improve awareness about lightning.”

As experts point out, technology can only work up to a point in rural areas, where a lack of smartphones to download apps, poor internet connectivity and a lack of mobile connectivity in remote areas make even text messaging ineffective.

In the National Disaster Management Plan 2019 published by the NDMA, it falls upon states to disseminate information received from the IMD to the public, using print/electronic/social and other mass media at the local level, and activate community-based early warning systems.

“Last mile connectivity is actually last person connectivity,” said Surya Prakash, head of the geo-meteorological hazards department at the National Institute of Disaster Management, New Delhi.

“The early warning needs to be communicated in the local language,” he explained. “All kinds of communication technologies are utilised--it can be newer technology such as mobiles, websites and television and there can be and should be traditional methods of mics and public warning systems such as town criers or even runners like in older times.”

Mrutyunjay Mohapatra, DG (Meteorology) at the IMD, had made a similar point in the South West Monsoon Lightning Report 2019. Managing the dissemination of information at village level focussing on farmers, poor, tribal and children will go a long way in mitigating risk and preventing precious loss of life, livestock and livelihoods, he said.

In one of the worst affected states, P.N. Rai of the Bihar State Disaster Management Authority (BSDMA) agreed that early warning systems at the community level were not as efficient as they should be to prevent deaths.

“Right now we get lightning predictions about 30 minutes in advance, which proves to be inadequate notice for people who are out in the field, for example farmers in their farmland, to get home or take shelter,” he told IndiaSpend. While training programmes are being conducted, “we still need to do more to improve further connectivity till the last person”, he said.

Lightning arresters

Clubbed with an effective EWS, simple lightning arresters can reduce fatalities during thunderstorms and lightning, experts say. These devices mitigate the effects of lightning strikes on power and telecommunication systems and protect individuals from strikes.

The basic lightning arrester is a metal rod installed at the highest point of a building or any other structure so that whenever there is a lightning strike, it hits this rod and is then safely conducted to ground/earth via a flat wire called earthing. The National Disaster Management Plan 2019 asks states to install these conductors.

Odisha has been the best performing state in this regard, Srivastava, the CROPC chairperson, said. Battered by cyclones in the past, it has ramped up its infrastructure with proactive measures to mitigate damage. Alongside, it has incorporated lightning resilience in its planning.

Ahead of Cyclone Fani in 2019, all 891 cyclone shelters in Odisha were fitted with lightning arresters, and consequently, there were no deaths due to lightning during May 3-4 that year, even though there were more than 100,000 intense lightning strikes, the South West Monsoon Lightning Report 2019 noted.

Compared to that, when Cyclone Fani advanced north-west, first to Jharkhand and Bihar and then to Uttar Pradesh, the cyclone force had weakened and there were lightning strikes of lesser intensity. “Yet, there were a total of 10 lightning deaths in those states during cyclone days,” Srivastava said.

In the 2019 monsoon, Uttar Pradesh saw 293 deaths due to lightning strikes, Madhya Pradesh 248 and Bihar 221. However, only 200 lives were lost to lightning in Odisha, despite it experiencing the highest number of lightning strikes, according to the South West Monsoon Lightning Report 2019.

While Bihar has prepared a Disaster Risk Reduction Roadmap 2015-2030, none of the Hazard Maps prepared by the BSDMA feature lightning.

Citing the example of the pilgrim town of Deoghar in Jharkhand, where lightning arresters have been installed atop several buildings in the famous Baba Dham temple complex, Srivastava, who was an adviser to the Jharkhand government on disaster management in 2016, said, “If Jharkhand and Odisha can do it, surely Bihar can do this and much more.”

Growing interest in monitoring lightning globally

There are no reliable figures available on the number of global deaths due to lightning strikes. Some countries do not count such deaths. However, as in India, there is a growing global interest in monitoring lightning activity closely, sparked by concerns over climate change, of which lightning is seen as a symptom as well as a cause.

Quoting previously published studies, a September 2018 research paper, Lightning: A New Essential Climate Variable, made two important points. First: “Lightning frequency is changing, as climate is changing. Lightning’s close relationship to thunderstorms and precipitation makes it a valuable indicator for storminess, which makes lightning a particularly useful means of observing a variable and changing climate.”

Secondly, it said, “lightning is not only an indicator of climate change; it also affects the global climate directly. Lightning produces nitrogen oxides, which are strong greenhouse gases.”

Acknowledging lightning as a new ‘Essential Climate Variable’, the Global Climate Observing System and the World Meteorological Organization’s Commission for Climatology established a Task Team for Lightning Observations for Climate Applications in October 2017.

“Model calculations suggest an increase in lightning flashes in a warmer climate,” Roy, the IMD scientist, said, “Some studies indicate a 10% increase in lightning per degree rise in temperature.”

“Lightning activity increases as regions become hotter and drier at the surface,” Roy said, “Cloud‐to‐ground lightning frequencies show larger sensitivity to climate change than intracloud frequencies.” However, there are variations, she added, citing a recent study that had projected a decrease of lightning due to a decrease in cloud ice content.

(Khandekar is an independent journalist based in Delhi. She writes on environmental and developmental issues.)

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@indiaspend.org. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.